星际天体

星际天体(Interstellar object)是指在星际空间中不受恒星引力束缚的天体,包括小行星、彗星、星际行星等,但不包括恒星。此术语也可应用于暂时接近恒星轨道上的物体,例如某些小行星和彗星(包括系外彗星[1][2])。在后一种情况下,该物体可能被称为星际干扰者(interstellar interloper)。[3]

最早发现的星际物体是星际行星,这些行星被从原来的恒星系统中弹射出来(例如OTS 44或蝘蜓座110913-773444),但它们很难与次棕矮星区分开来,后者是在星际空间中形成的与恒星相似的质量物体。

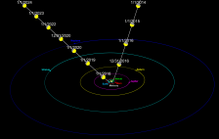

首个在太阳系中发现并经过的星际物体是2017年的斥候星。第二个是2019年的2I/鲍里索夫彗星。它们都具有显著的双曲线超出速度,表明它们并非起源于太阳系。美国太空司令部在2022年确认了一个星际天体于2014年撞击地球的事件。[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]2023年5月,天文学家报告了多年来在近地轨道中可能俘获到的其他星际天体。[11][12]

定义

随着在太阳系中首次发现星际天体,国际天文学联合会提出了一个新的星际物体小天体编号系列,称为I数字,类似于彗星编号系统。这些编号将由小行星中心指定。对于星际物体的临时指定将使用相应的C/或A/前缀(彗星或小行星)。[13]

概述

| 名称 | 速度 |

|---|---|

| 艾桑彗星 (弱双曲 奥尔特云彗星) |

0.2公里/秒 0.04天文单位/年[14] |

| 航海家一号 (用于比较) |

16.9公里/秒 3.57天文单位/年[15] |

| 斥候星 | 26.33公里/秒 5.55天文单位/年[16] |

| 2I/鲍里索夫彗星 | 32.1公里/秒 6.77天文单位/年[17] |

| CNEOS 2014-01-08 (同行评审中) |

43.8公里/秒 9.24天文单位/年[18] |

天文学家估计,每年会有几个外太阳系起源的星际物体(如斥候星)穿越地球轨道内部[19],并且每天有10,000个物体穿越海王星轨道内部[20]。

星际彗星偶尔会以随机速度穿越内太阳系[1],并朝向大犬座的方向前进,因为太阳系正朝着那个方向(称为太阳向点)移动。在斥候星被发现之前,尚未观察到任何速度大于太阳逃逸速度的彗星,这一事实被用来为其在星际空间中的密度设置上限。[21]根据Torbett的一篇论文指出,彗星的密度不超过每立方秒差距10^13(一兆)颗彗星[22]。来自LINEAR的其他分析将上限定为4.5×10−4/AU^3,或每立方秒差距10^12(一兆)颗彗星[2]。大卫·C·朱伊特(David C. Jewitt)及其同事在斥候星被检测到后进行的一项最新估计预测,海王星轨道内部类似的100米尺度星际物体的稳定状态人口约为1×10^4,每个物体的停留时间约为10年[23]。

根据奥尔特云形成的当前模型预测,被弹射到星际空间的彗星数量多于保留在奥尔特云中的彗星,估计多出3到100倍不等[2]。其他模拟表明,90%至99%的彗星被弹射[24]。没有理由相信在其他恒星系统中形成的彗星不会同样被散布[1]。阿米尔·西拉吉(Amir Siraj)和亚伯拉罕·勒布证明,奥尔特云可能是由太阳的诞生星团中的其他恒星弹射出的类地体形成的[25][26][27]。

恒星周围的物体可能因与第三颗大质量天体的相互作用而被弹射,从而成为星际物体。这样的过程始于1980年代初,当时C/1980 E1最初与太阳有引力束缚,但在靠近木星时受到足够加速达到太阳系的逃逸速度。改变了它的轨道,使其由椭圆轨道变为双曲线轨道,并使其成为当时已知最偏心的物体,其轨道离心率为1.057[28]。它正朝着星际空间前进。

由于目前观测的困难,一个星际物体通常只有在穿越太阳系时才能被检测到,其可通过其明显的双曲线轨迹和超出数公里/秒的双曲线超出速度来加以区分,这证明了它不受太阳引力束缚[2][29]。相比之下,受引力束缚的物体会围绕太阳拥有椭圆轨道运行。有一些物体的轨道非常接近抛物线,使得它们受引力束缚的状态不明确。

星际彗星可能在穿越太阳系时偶尔被俘为日心轨道。计算机模拟显示,只有木星的质量足够大才能俘获星际物体,并且预计每六千万年会发生一次[22]。梅克贺兹一号彗星和百武二号彗星可能是这样的彗星的例子。它们在太阳系中具有非典型的化学组成[21][30]。

最近的研究表明,小行星514107可能是一个过去的星际物体,它在约45亿年前被俘获,这一点可以从它与木星的共轨运动和绕太阳的逆行轨道得到证明[31] 。此外,彗星C/2018_V1有着很高的可能性(72.6%)来自太阳系外的恒星系统,尽管无法排除它来自奥尔特云的可能性[32] 。哈佛大学的天文学家提出了物质——以及潜伏的孢子——可以在远距离传播的可能性[33]。斥候星在内太阳系的探测,星际天体确认了与系外行星系统之间可能存在着物质联系的可能性。

太阳系中最小的星际尘埃颗粒受到电磁力的过滤,而最大的颗粒则因稀疏,而无法从航天器探测器中获得良好的统计数据。对于中等(0.1-1微米)大小的星际天体的区别可能是一个挑战。这些颗粒的速度和方向性可能有着剧烈的变化[35]。因此在地球大气中作为流星观测到的星际陨石的识别非常具有挑战性,需要高精度的测量和适当的误差检查[36]。否则,测量误差可能将近抛物线轨道转换为超抛物线的极限,并创造出一个人为的双曲粒子群,通常被解释为星际来源。[33]

大型的星际天体先后于2017年(斥候星)和2019年(2I/鲍里索夫彗星)首次在太阳系中被检测到,西拉吉和勒布提出寻找类似于斥候星,与木星的近距离相互作用中通过失去轨道能量而被困在太阳系中星际天体的建议。并指出未来的天文巡天调查如[[薇拉·鲁宾天文台],该天文台将能够通过太阳相对于局部静止系的运动,检测到星际天体分布的非各向同性,并确定星际物体从其母星系中的特征射速]的观测,应该能找到许多候选物体。[37][38][39][40][41]

2023年5月,天文学家报告了多年来在近地轨道(NEO)中可能俘获到的其他星际天体[11][12]。

2023年7月,哈佛大学的天文学家阿维·洛伊布报告了寻找星际物质的可能性[42] 。

已确认天体

1I/2017 U1

|

主条目:斥候星 |

2017年10月19日,泛星计划望远镜发现一个暗淡的物体,视星等约为20。观测结果显示,它以一个明显的双曲线轨道绕太阳运行,速度超过太阳的逃逸速度,这意味着它并非受太阳系引力束缚,很可能是一个星际天体[43]。最初它被命名为C/2017 U1,因为当时认为它是一颗彗星,但经过长时间观测研究后,发现其不具有彗发构造,也不是小行星,因此更名为A/2017 U1[44][45]。在确认它的星际性质后,它被重新命名为1I/ʻ斥候星(Oumuamua) — 其中“1”表示它是首次发现的这种物体,“I”则代表星际,而“Oumuamua”则为夏威夷语,意为“第一个来自远方的信使”。[46]

斥候星缺乏彗发的情况表明它来自它来源恒星系统的内部区域,在冻结线内失去了所有的表面挥发物,类似于太阳系中的岩石小行星、熄火彗星、达摩克型小行星一样。然而这仅为假设,因为斥候星有可能在星际空间经过漫长的宇宙线照射后失去了所有表面挥发物,从而在被其母系统排斥后形成了厚厚的外壳层。

斥候星的离心率为1.199,是在发现2019年8月的2I/鲍里索夫彗星之前,太阳系中观测到的任何物体的离心率之最。2018年9月,天文学家描述了几个可能为斥候星所属的恒星系统[47][48]

2I/鲍里索夫彗星

|

主条目:2I/鲍里索夫彗星 |

这个物体由根纳季·鲍里索夫于2019年8月30日在克里米亚瑙奇内的MARGO观测站使用他自己打造的0.65米望远镜发现的[49]。在2019年9月13日,加那利大型望远镜获得2I/鲍里索夫彗星的低分辨率可见光谱,显示这个物体的表面组成与典型的奥尔特云彗星相差不大[50][51][52]。

国际天文学联合会(IAU)小天体命名工作组保留了鲍里索夫这个名字,将这颗彗星命名为2I/鲍里索夫(Borisov),表示它是一个星际天体[53]。2020年3月12日,天文学家报告了来自鲍里索夫彗星“持续的核心碎裂”的观测证据[54] 。

候补天体

2007年,Afanasiev等人曾报告称在2006年7月28日时,俄罗斯科学院特设天体物理台上空的大气层中检测了一个直径几厘米的星际陨石撞击事件[55] 。

2018年11月,哈佛大学的天文学家西拉吉和勒布报告称,根据计算出的轨道特征,太阳系中应该有数百个如斥候星大小的星际天体,并提出了几个半人马座的候选物,如2017 SV13和2018 TL6[56]。这些物体目前围绕绕太阳运行,但可能在遥远的过去被引力俘获。

西拉吉和勒布也出了增加星际物天际发率的方法,包括掩星、与月球或地球大气层碰撞的光学特征,以及与中子星碰撞产生的射电耀斑[57][58][59][60]。

2014年星际流星

|

主条目:CNEOS 2014-01-08 |

CNEOS 2014-01-08(又称星际陨石1;IM1)[61][62][63]是一颗质量为0.46吨、宽度为0.45米(1.5英尺)的流星,在2014年1月8日燃烧于地球大气层中[7][10]。根据2019年的一份预印本,指出这颗陨石可能来自星际空间[64][65][5][6][9]。它的日心速度为60千米/秒(37英里/秒),渐近速度为42.1 ± 5.5千米/秒(26.2 ± 3.4英里/秒),并于协调世界时17:05:34在巴布亚新几内亚附近的高度18.7千米(61,000英尺)处爆炸[7]。在2022年4月解密数据后[66],根据避免小行星撞击防御传感器收集的信息,美国太空司令部证实了潜在的星际陨石的速度[8][4]。伽利略计划对此调查进行一次探险,以回收这颗明显不寻常的陨石的小碎片[67][68][69][70][69]。

其他天文学家对该流星来自星际的起源表示怀疑,因为使用的流星目录并未报告入射速度的误差棒[71]。任何单一数据点的有效性(尤其是对于较小的流星体)仍然存在问题。

2022年11月曾发表了一篇论文,声称CNEOS 2014-01-08的异常特性(包括其高强度和明显的双曲线轨迹)更可能是测量误差而不是真实参数。由于常见的微小陨石体之间无法区分,因此能够成功回收任何流星体碎片的可能性非常低。[72]。

2017年星际流星

|

主条目:CNEOS 2017-03-09 |

CNEOS 2017-03-09(又称星际陨石2;IM2)[62][63]是一颗质量约为6.3吨的流星,于2017年3月9日燃烧于地球大气层中。[73][62] 。 在2022年9月,西拉吉和勒布报告了一颗候选星际陨石的发现,即CNEOS 2017-03-09,根据陨石的高材料强度,在某种程度上被认为是可能的星际天体[62][63]。

假设任务

依据现有的太空技术,由于星际天体的高速度,对于近距离访问天体和轨道任务具有挑战性,但并非不可能。[74][75]

星际研究计划倡议(i4is)于2017年发起了天琴座计划,以评估对斥候星进行探测任务的可行性[76]。在5至10年内将航天器送到奥陌陌的建议选择是基于首先使用木星飞行,然后在3至10太阳半径进行近距离太阳飞行,以利用奥伯特效或更先进的选择,如太阳帆、激光帆和核推进。[77]

欧洲太空总署(ESA)和宇宙航空研究开发机构(JAXA)计划于2029年发射的彗星拦截器将被定位在拉格朗日点L2点,等待合适的长周期彗星进行拦截和飞越研究[78]。如果在3年的等待期间找不到合适的彗星,太空船在短时间内也可以被指派拦截星际天体(若可到达)。[79]

另见

- 全球灾难危机 ——潜在有害的全球事件

- 双曲线小行星 – 不绕太阳运行的天体

- 双曲彗星列表 - 可能不绕太阳运行的彗星

- 按最大远日点列出的太阳系天体列表

参考文献

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Valtonen, Mauri J.; Zheng, Jia-Qing; Mikkola, Seppo. Origin of oort cloud comets in the interstellar space. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. March 1992, 54 (1–3): 37–48. Bibcode:1992CeMDA..54...37V. S2CID 189826529. doi:10.1007/BF0004954.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3

Francis, Paul J. The Demographics of Long-Period Comets. The Astrophysical Journal. 2005-12-20, 635 (2): 1348–1361. Bibcode:2005ApJ...635.1348F. S2CID 12767774. arXiv:astro-ph/0509074

. doi:10.1086/497684.

. doi:10.1086/497684.

- ^ Veras, Dimitri. Creating the first interstellar interloper. Nature Astronomy. 13 April 2020, 4 (9): 835–836. Bibcode:2020NatAs...4..835V. ISSN 2397-3366. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1064-9

.

.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 United States Space Command. "I had the pleasure of signing a memo with @ussfspoc's Chief Scientist, Dr. Mozer, to confirm that a previously-detected interstellar object was indeed an interstellar object, a confirmation that assisted the broader astronomical community.. Twitter. 6 April 2022 [12 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-16).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Ferreira, Becky. Secret Government Info Confirms First Known Interstellar Object on Earth, Scientists Say – A small meteor that hit Earth in 2014 was from another star system, and may have left interstellar debris on the seafloor.. Vice News. 7 April 2022 [9 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-18).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Wenz, John. "It Opens A New Frontier Where You're Using The Earth As A Fishing Net For These Objects." – Harvard Astronomer Believes An Interstellar Meteor (or Craft) Hit Earth In 2014. Inverse. 11 April 2022 [11 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-14).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Discovery of a Meteor of Interstellar Origin. 4 June 2019. arXiv:1904.07224

[astro-ph.EP].

[astro-ph.EP].

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Handal, Josh; Fox, Karen; Talbert, Tricia. U.S. Space Force Releases Decades of Bolide Data to NASA for Planetary Defense Studies. NASA. 8 April 2022 [11 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-26).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Siraj, Amir. Spy Satellites Confirmed Our Discovery of the First Meteor from beyond the Solar System - A high-speed fireball that struck Earth in 2014 looked to be interstellar in origin, but verifying this extraordinary claim required extraordinary cooperation from secretive defense programs. Scientific American. 12 April 2022 [14 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-05).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Roulette, Joey. Military Memo Deepens Possible Interstellar Meteor Mystery – The U.S. Space Command seemed to confirm a claim that a meteor from outside the solar system had entered Earth's atmosphere, but other scientists and NASA are still not convinced. (+ Comment). The New York Times. 15 April 2022 [15 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-03).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Gough, Evan. A Few Interstellar Objects Have Probably Been Captured. Universe Today. 18 May 2023 [19 May 2023]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-04).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Mukherjee, Diptajyoti; Siraj, Amir; Trac, Hy; Loeb, Abraham. Close Encounters of the Interstellar Kind: Examining the Capture of Interstellar Objects in Near Earth Orbit. 2023. arXiv:2305.08915

[astro-ph.EP].

[astro-ph.EP].

- ^ MPEC 2017-V17 : NEW DESIGNATION SCHEME FOR INTERSTELLAR OBJECTS. Minor Planet Center. 6 November 2017 [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-26).

- ^ C/2012 S1 (ISON) had an epoch 1600 barycentric semi-major axis of −145127 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) and would have an inbound v_infinite of 0.2 km/s at 50000 au:

v=42.1219 √1/50000 − 0.5/−145127 - ^ Voyager Fast Facts. [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-22).

- ^ Gray, Bill. Pseudo-MPEC for A/2017 U1 (FAQ File). Project Pluto. 26 October 2017 [26 October 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-26).

- ^ Gray, Bill. FAQ for C/2019 Q4 (Borisov). Project Pluto. [2019-09-24]. (原始内容存档于2019-09-19).

- ^

Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Discovery of a Meteor of Interstellar Origin. 2019. arXiv:1904.07224

[astro-ph.EP].

[astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Interstellar Asteroid FAQs. NASA. 20 November 2017 [21 November 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-01).

- ^ Fraser, Wesley. The Sky at Night: The Mystery of ʻOumuamua. 访谈 with Chris Lintott. BBC. 11 February 2018.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 MacRobert, Alan. A Very Oddball Comet. Sky & Telescope. 2008-12-02 [2010-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2008-12-07).

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Torbett, M. V. Capture of 20 km/s approach velocity interstellar comets by three-body interactions in the planetary system. Astronomical Journal. July 1986, 92: 171–175. Bibcode:1986AJ.....92..171T. doi:10.1086/114148.

- ^

Jewitt, David; Luu, Jane; Rajagopal, Jayadev; Kotulla, Ralf; Ridgway, Susan; Liu, Wilson; Augusteijn, Thomas. Interstellar Interloper 1I/2017 U1: Observations from the NOT and WIYN Telescopes. The Astrophysical Journal. 2017, 850 (2): L36. Bibcode:2017ApJ...850L..36J. S2CID 32684355. arXiv:1711.05687

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa9b2f.

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa9b2f.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. The Enduring Mysteries of Comets. Space.com. 2007-12-24 [2008-12-30]. (原始内容存档于2010-09-17).

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. The Case for an Early Solar Binary Companion. The Astrophysical Journal. 2020-08-18, 899 (2): L24 [2023-07-14]. Bibcode:2020ApJ...899L..24S. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 220665422. arXiv:2007.10339

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abac66. (原始内容存档于2023-04-08) (英语).

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abac66. (原始内容存档于2023-04-08) (英语).

- ^ Carter, Jamie. Was Our Sun A Twin? If So Then 'Planet 9' Could Be One Of Many Hidden Planets In Our Solar System. Forbes. [2020-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

- ^ Did the Sun have an early binary companion?. Cosmos Magazine. 2020-08-20 [2020-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-16) (澳大利亚英语).

- ^ JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/1980 E1 (Bowell) (1986-12-02 last obs). [2010-01-08]. (原始内容存档于2019-09-13).

- ^

de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Aarseth, Sverre J. Where the Solar system meets the solar neighbourhood: patterns in the distribution of radiants of observed hyperbolic minor bodies. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 6 February 2018, 476 (1): L1–L5. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.476L...1D. S2CID 119405023. arXiv:1802.00778

. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sly019.

. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sly019.

- ^ Mumma, M. J.; Disanti, M. A.; Russo, N. D.; Fomenkova, M.; Magee-Sauer, K.; Kaminski, C. D.; Xie, D. X. Detection of Abundant Ethane and Methane, Along with Carbon Monoxide and Water, in Comet C/1996 B2 Hyakutake: Evidence for Interstellar Origin. Science. 1996, 272 (5266): 1310–1314. Bibcode:1996Sci...272.1310M. PMID 8650540. S2CID 27362518. doi:10.1126/science.272.5266.1310.

- ^ Clery, Daniel. This asteroid came from another solar system—and it's here to stay. Science. 2018. doi:10.1126/science.aau2420.

- ^ Reuell, Peter. Harvard study suggests asteroids might play key role in spreading life. Harvard Gazette. 8 July 2019 [29 September 2019]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-25).

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Hajdukova, M.; Sterken, V.; Wiegert, P.; Kornoš, L. The challenge of identifying interstellar meteors. Planetary and Space Science. 2020-11-01, 192: 105060. Bibcode:2020P&SS..19205060H. ISSN 0032-0633. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2020.105060

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Hajdukova, Maria; Sterken, Veerle; Wiegert, Paul; Kornoš, Leonard. The challenge of identifying interstellar meteors. Planetary and Space Science. 2020-11-01, 192: 105060. Bibcode:2020P&SS..19205060H. ISSN 0032-0633. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2020.105060

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Sterken, V. J.; Altobelli, N.; Kempf, S.; Schwehm, G.; Srama, R.; Grün, E. The flow of interstellar dust into the solar system. Astronomy & Astrophysics. 2012-02-01, 538: A102 [2023-07-14]. Bibcode:2012A&A...538A.102S. ISSN 0004-6361. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117119

. (原始内容存档于2022-05-26) (英语).

. (原始内容存档于2022-05-26) (英语).

- ^ Hajduková, Mária; Kornoš, Leonard. The influence of meteor measurement errors on the heliocentric orbits of meteoroids. Planetary and Space Science. 2020-10-01, 190: 104965. Bibcode:2020P&SS..19004965H. ISSN 0032-0633. S2CID 224927095. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2020.104965 (英语).

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Identifying Interstellar Objects Trapped in the Solar System through Their Orbital Paramteters. The Astrophysical Journal. 2019, 872 (1): L10. Bibcode:2019ApJ...872L..10S. S2CID 119198820. arXiv:1811.09632

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a.

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a.

- ^ Koren, Marina. When a Harvard Professor Talks About Aliens – News about extraterrestrial life sounds better coming from an expert at a high-prestige institution.. The Atlantic. 23 January 2019 [23 January 2019]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-09).

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Observable Signatures of the Ejection Speed of Interstellar Objects from Their Birth Systems. The Astrophysical Journal. 2020-10-29, 903 (1): L20 [2023-07-14]. Bibcode:2020ApJ...903L..20S. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 222141714. arXiv:2010.02214

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abc170. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abc170. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

- ^ Williams, Matt. Vera Rubin Should be Able to Detect a Couple of Interstellar Objects a Month. Universe Today. 2020-11-07 [2020-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (美国英语).

- ^ Clery, Daniel. Project launched to look for extraterrestrial visitors to our Solar System. www.science.org. 2021-07-26 [2021-10-22]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-25) (英语).

- ^ Loeb, Avi. I'm a Harvard Astronomer. I Think We Found Interstellar Material. Newsweek. 5 July 2023 [7 July 2023]. (原始内容存档于7 July 2023).

- ^ MPEC 2017-U181: COMET C/2017 U1 (PANSTARRS). Minor Planet Center. [25 October 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-25).

- ^ Meech, K. Minor Planet Electronic Circular MPEC 2017-U183: A/2017 U1. Minor Planet Center. 25 October 2017 [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-26).

- ^ We May Just Have Found An Object That Originated From Outside Our Solar System. IFLScience. October 26, 2017 [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-29).

- ^ Aloha, 'Oumuamua! Scientists confirm that interstellar asteroid is a cosmic oddball. GeekWire. 20 November 2017 [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-02).

- ^

Feng, Fabo; Jones, Hugh R. A. Plausible home stars of the interstellar object 'Oumuamua found in Gaia DR2. The Astronomical Journal. 2018, 156 (5): 205. Bibcode:2018AJ....156..205B. S2CID 119051284. arXiv:1809.09009

. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aae3eb.

. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aae3eb.

- ^ 'Oumuamua Isn't from Our Solar System. Now We May Know Which Star It Came From. [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-25).

- ^ King, Bob. Is Another Interstellar Visitor Headed Our Way?. Sky & Telescope. 11 September 2019 [12 September 2019]. (原始内容存档于2019-09-12).

- ^ The Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) obtains the visible spectrum of C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), the first confirmed interstellar comet. Instituto Astrofisico de Canarias. 14 September 2019 [2019-09-14]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-27).

- ^ de León, Julia; Licandro, Javier; Serra-Ricart, Miquel; Cabrera-Lavers, Antonio; Font Serra, Joan; Scarpa, Riccardo; de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl. Interstellar Visitors: A Physical Characterization of Comet C/2019 Q4 (Borisov) with OSIRIS at the 10.4 m GTC. Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society. 19 September 2019, 3 (9): 131. Bibcode:2019RNAAS...3..131D. S2CID 204193392. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab449c.

- ^ de León, J.; Licandro, J.; de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R.; Lara, L. M.; Moreno, F.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Serra-Ricart, M.; De Prá, M.; Tozzi, G. P.; Souza-Feliciano, A. C.; Popescu, M.; Scarpa, R.; Font Serra, J.; Geier, S.; Lorenzi, V.; Harutyunyan, A.; Cabrera-Lavers, A. Visible and near-infrared observations of interstellar comet 2I/Borisov with the 10.4-m GTC and the 3.6-m TNG telescopes. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 30 April 2020, 495 (2): 2053–2062 [2023-07-14]. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.495.2053D. S2CID 218486809. arXiv:2005.00786v1

. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa1190. (原始内容存档于2021-02-25).

. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa1190. (原始内容存档于2021-02-25).

- ^ MPEC 2019-S72 : 2I/Borisov=C/2019 Q4 (Borisov). Minor Planet Center. [24 September 2019]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-22).

- ^ Drahus, Michal; et al. ATel#1349: Multiple Outbursts of Interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov. The Astronomer's Telegram. 12 March 2020 [13 March 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-22).

- ^ Afanasiev, V. L.; Kalenichenko, V. V.; Karachentsev, I. D. Detection of an intergalactic meteor particle with the 6-m telescope. Astrophysical Bulletin. 1 December 2007, 62 (4): 301–310. Bibcode:2007AstBu..62..301A. ISSN 1990-3421. S2CID 16340731. arXiv:0712.1571

. doi:10.1134/S1990341307040013.

. doi:10.1134/S1990341307040013.

- ^

Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Identifying Interstellar Objects Trapped in the Solar System through Their Orbital Parameters. The Astrophysical Journal. 2019, 872 (1): L10. Bibcode:2019ApJ...872L..10S. S2CID 119198820. arXiv:1811.09632

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a.

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Detecting Interstellar Objects through Stellar Occultations. The Astrophysical Journal. 2020-02-26, 891 (1): L3 [2023-07-14]. Bibcode:2020ApJ...891L...3S. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 210116475. arXiv:2001.02681

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab74d9. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab74d9. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. A real-time search for interstellar impacts on the moon. Acta Astronautica. 2020-08-01, 173: 53–55. Bibcode:2020AcAau.173...53S. ISSN 0094-5765. S2CID 201645069. arXiv:1908.08543

. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2020.04.006 (英语).

. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2020.04.006 (英语).

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham. Radio Flares from Collisions of Neutron Stars with Interstellar Asteroids. Research Notes of the AAS. 2019-09-19, 3 (9): 130 [2023-07-14]. Bibcode:2019RNAAS...3..130S. ISSN 2515-5172. S2CID 201698501. arXiv:1908.11440

. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab43de. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab43de. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

- ^ August 2019, Mike Wall 30. A Telescope Orbiting the Moon Could Spy 1 Interstellar Visitor Per Year. Space.com. 30 August 2019 [2020-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14) (英语).

- ^ Pultarova, Tereza. Confirmed! A 2014 meteor is Earth's 1st known interstellar visitor - Interstellar space rocks might be falling to Earth every 10 years.. Space.com. 3 November 2022 [4 November 2022]. (原始内容存档于2022-11-07).

- ^ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Avi. Interstellar Meteors are Outliers in Material Strength. The Astrophysical Journal. 20 September 2022, 941 (2): L28. Bibcode:2022ApJ...941L..28S. S2CID 252407502. arXiv:2209.09905v1

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aca8a0.

. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aca8a0.

- ^ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Loeb, Avi. The discovery of a second interstellar meteor. TheDebrief.org. 23 September 2022 [24 September 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-08).

- ^ Billings, Lee. Did a Meteor from Another Star Strike Earth in 2014? – Questionable data cloud the potential discovery of the first known interstellar fireball. Scientific American. 23 April 2019 [12 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14).

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. The First Known Interstellar Meteor May Have Hit Earth in 2014 – The 3-foot-wide rock rock visited us three years before 'Oumuamua.. Space.com. 16 April 2019 [12 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-02).

- ^ Specktor, Brandon. An interstellar object exploded over Earth in 2014, declassified government data reveal – Classified data prevented scientists from verifying their discovery for 3 years.. Live Science. 11 April 2022 [12 April 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-03-25).

- ^ Loeb, Avi. The First Interstellar Meteor Had a Larger Material Strength Than Iron Meteorites. Medium. 18 April 2022 [21 August 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-10) (英语).

- ^ Fuschetti, Ray; Johnson, Malcolm; Strader, Aaron. Harvard Professor Believes Alien Tech Could Have Crashed Into Pacific Ocean — And He Wants to Find It. NBC Boston. [2 September 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-30).

- ^ 69.0 69.1 Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham; Gallaudet, Tim. An Ocean Expedition by the Galileo Project to Retrieve Fragments of the First Large Interstellar Meteor CNEOS 2014-01-08. 5 August 2022. arXiv:2208.00092

[astro-ph.EP].

[astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Carter, Jamie. Astronomers plan to fish an interstellar meteorite out of the ocean using a massive magnet. livescience.com. 9 August 2022 [21 August 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-04) (英语).

- ^ Billings, Lee. Did a Meteor from Another Star Strike Earth in 2014. Scientific American. 2019-04-23 [2019-04-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-14).

- ^ Vaubaillon, J., Hyperbolic meteors: is CNEOS 2014-01-08 interstellar?, WGN, 2022, 50 (5): 140, Bibcode:2022JIMO...50..140V, arXiv:2211.02305

- ^ Alien-Hunting Astronomer Says There May Be a Second Interstellar Object on Earth in New Study. Vice. [3 November 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-21) (英语).

- ^ Seligman, Darryl; Laughlin, Gregory. The Feasibility and Benefits of in situ Exploration of ʻOumuamua-like Objects. The Astronomical Journal. 12 April 2018, 155 (5): 217. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..217S. S2CID 73656586. arXiv:1803.07022

. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aabd37.

. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aabd37.

- ^ Ferreira, Becky. We Need to Intercept Our Next Interstellar Visitor to See If It's Artificial, Astronomers Say in New Study - A new study games out a mission to intercept an interstellar object in space and get a close-up look to see just what its made of.. Vice. 8 November 2022 [8 November 2022]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-29).

- ^ Project Lyra – A Mission to ʻOumuamua. Initiative for Interstellar Studies. [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-03).

- ^ Hein. Project Lyra: Sending a Spacecraft to 1I/ʻOumuamua (former A/2017 U1), the Interstellar Asteroid. arXiv:1711.03155

.

.

- ^ Ariel moves from blueprint to reality. ESA. 12 November 2020 [12 November 2020]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-16).

- ^ O'Callaghan, Jonathan. European Comet Interceptor Could Visit an Interstellar Object. Scientific American. 24 June 2019 [2023-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2021-12-15).

外部链接

- Engelhardt, Toni; Jedicke, Robert; Vereš, Peter; Fitzsimmons, Alan; Denneau, Larry; Beshore, Ed; Meinke, Bonnie. An Observational Upper Limit on the Interstellar Number Density of Asteroids and Comets. The Astronomical Journal. 2017, 153 (3): 133. Bibcode:2017AJ....153..133E. S2CID 54893830. arXiv:1702.02237

. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa5c8a.

. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa5c8a.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.