农业

|

| 农业和农学 |

|---|

| 农业史 |

| 农业 |

| 其他类型 |

| 有关 |

| 分类 |

|

|

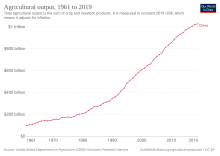

农业属于第一级产业,包括作物种植、畜牧、渔业养殖、林业等活动,负责主副食和经济作物供应。[1]农业的主要产品是食物、纤维、能源和原材料(例如橡胶),其中食物包括谷物、蔬菜、水果、食用油、肉类、奶制品、蛋和菌类。全球农业年产出约110亿吨食物[2],3200万吨自然纤维[3]和40亿立方米木材。[4]不过,其中有14%的食物在到达零售环节之前被浪费。[5]自20世纪开始,基于单一作物种植的工业化农业开始成为世界农业产出的主要来源。

农业的出现是人类文明转向定居形式的里程碑,借由野生动植物的驯化、培育与繁殖,人们获得了充足的食物与资源,并促进早期城市的发展与成型。人类在10.5万年前开始从野外采集谷物,但直到1.15万年前才开始种植,并在大约1万年前驯化了绵羊、山羊、猪、牛等家畜。世界上至少有11个地区独立发展出了作物种植。

现代农业技术、植物育种、农业化学产品(例如杀虫剂和化肥)的发展显著增加了作物产量,但也引发了诸多生态与环境问题。选择育种和现代畜牧业技术发展增加了肉类制品产量,但也引发了动物福利和环境忧虑。上述环境问题包括气候变化、地下含水层枯竭、森林砍伐、抗生素耐药性和农业相关污染。农业既是环境退化的原因,也深受其影响,生物多样性丧失、荒漠化、土壤退化、气候变化等因素都会降低作物产量。进入21世纪后,可持续农业的比例渐渐提高,包括朴门和有机农业,着重在生态平衡与就近百里饮食。转基因作物被广泛使用,但也有部分国家禁止此类作物种植。

定义

根据东汉时期《说文解字》和清康熙时期《康熙字典》的解释,“农”字都是“耕种”的意思,这表示在中国古代就只有种植业才会被称作“农业”。但现代对农业的定义更加广泛,包括利用自然资源生产维持生命所需的物品,如食物、纤维、林业产品、园艺作物,以及与之相关的服务。[6]因此,广义的农业包括种植业、园艺、动物养殖(畜牧业、水产养殖等)和林业,但有时园艺和林业也被排除在外。[6]此外,农业可因管理对象不同而分为两类:植物农业,主要涉及作物的培育;动物农业,主要关注农业动物产品。[7]

历史

|

主条目:农业史 |

起源

|

主条目:新石器革命 |

得益于农业发展,世界人口数量相比狩猎采集时代有了显著增长。[10]农业独立起源于多个地区[11],根据分类单元至少可归为11个起源中心。[8]早在10.5万年前,人们就已开始采集并食用野生谷物。[12]在23,000年前新石器时代的黎凡特,人们开始在加利利海附近种植二粒小麦、大麦和燕麦。[13][14]中国先民于13,500-8200年驯化了水稻,已知最早耕种时间距今约7,700年[15],而后绿豆、大豆、红豆也在此区域驯化。美索不达米亚人于13,000-11,000年前驯化了绵羊。[16]而家牛则是从10,500年前生活在现今土耳其和巴基斯坦地区的原牛驯化而来。[17]家猪由野猪驯化而来,此过程在欧洲、东亚和东南亚独立进行[18],最早驯化时间距今约10,500年。[19]在南美洲安第斯山脉,人们在10,000-7,000年前驯化了马铃薯,后续又驯化了豆子、古柯、羊驼、大羊驼和豚鼠。高粱于7,000年前在非洲萨赫勒被驯化。棉花于5,600年前在秘鲁被驯化[20],后也在欧亚大陆独立驯化。玉米源于野生玉蜀黍属,于6,000年前在中美洲驯化。[21]公元前3,500年左右,马在欧亚大草原被驯化。[22]关于农业的起源有大量研究,学者为此提出了众多假说。人类从狩猎采集向农业社会的转型伴随着集约化和定居的发展,相关过渡期案例有黎凡特地区的纳图夫文化和中国早期的新石器文化。随着生活方式的转变,人们开始在定居点种植采集自野外的资源,由此导致这些物种的逐步驯化。[23][24][25]

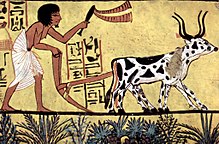

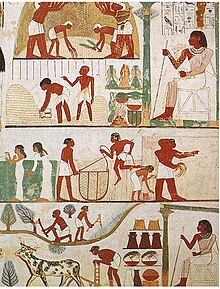

古代文明

公元前8,000年,欧亚大陆的苏美尔人开始以村庄形式定居,并依靠底格里斯河和幼发拉底河灌溉作物。其公元前3,000年的象形符号中出现了犁,公元前2,300年出现了播种犁。苏美尔农夫种植大麦、小麦、蔬菜(例如扁豆和洋葱)、水果(例如椰枣、葡萄和无花果)。[27]古埃及农业始于旧石器时代末期的前王朝时期,时间大约在公元前10,000年,主要依靠尼罗河和当地季节性洪水灌溉作物。当地人种植的主要粮食作物为大麦和小麦,此外还有亚麻和纸莎草等经济作物。[28][29]印度先民在公元前9,000年前驯化了小麦、大麦和枣,后续又驯化了绵羊和山羊。[30]在公元前8,000-6,000年的梅赫尔格尔文化中,巴基斯坦先民驯化了牛、绵羊和山羊。[31][32][33]棉花在公元前4-5世纪驯化。[34]此外,考古证据显示,在公元前2,500年的印度河流域文明中,出现了使用动物牵引的犁。[35]

在中国地区,公元前5世纪开始出现谷仓建筑,以及以获取丝绸为目的的蚕业。[36]公元1世纪开始使用水磨[37]和水利灌溉[38],公元2世纪晚期开始出现带有金属犁铧和犁板的重型犁[39][40],随后这些技术向西在欧亚大陆传播。[41]借助基因分子钟估算,亚洲水稻的驯化时间大约在8,200-13,500年前[42],驯化地点位于中国西南部的珠江流域,原始物种为野生稻。[43]古希腊和古罗马种植的主要谷物为小麦、二粒小麦和大麦,蔬菜包括豌豆、大豆和橄榄,绵羊和山羊养殖主要是为获取奶制品。[44][45]

中美洲驯化的谷物有南瓜、大豆、可可[46],其中可可是由居住在亚马孙河上游的马由-钦奇佩文化先民驯化,时间大约在公元前3,000年。[47]火鸡可能在墨西哥或美洲西南部驯化。[48]中美洲阿兹特克人发展了灌溉系统,在山坡上耕作梯田,为土壤施肥,建造人工浮田和人工岛。生活在美洲中部的玛雅人从公元前400年开始大量建造人工河道,以在沼泽地带开拓农田。[49][50][51][52][53]古柯由南美洲安第斯山脉先民驯化,在同一地区驯化的作物还有花生、番茄、烟草和菠萝。[46]棉花在公元前3,600年的秘鲁驯化[54],同在此地驯化的动物还包括羊驼、大羊驼、豚鼠。[55]北美东部原住民驯化了向日葵、烟草[56]、南瓜和藜属作物[57][58],人们也从野外采集野生稻米和枫糖。[59]人工驯化的草莓源自智利和北美野生物种的杂交,后由欧洲与北美人进一步驯化。[60]北美西南部和太平洋西北地区原住民种植树林,并有计划的引燃林火。原住民会控制树林火势,将其限制在特定区域,借此创造有利于农业持续发展的林火生态。[61][62][63][64]北美原住民还发展了一种名为“三姐妹”的同伴种植系统,这三种作物为冬南瓜、玉米和荷包豆。[65][66]

普遍认为澳大利亚原住民是游牧的狩猎采集者,他们会有计划地在野外放火,可能是为了增加火棍农耕中野生作物的产量。[67]学者指出,狩猎采集者需要让周围环境中野生作物产量维持在特定水平,只有这样才可在不耕作的情况下满足生存需求。新几内亚森林中可食用植物较为稀少,因此当地先民可能会实行“选择性放火”,以提高野生高大贝叶棕的果实产量。[68]

澳大利亚贡迪吉马拉人自5,000年开始饲养鳗鱼。[69]澳洲中西部海岸和中东部海岸先民曾种植山药、本地小米、野洋葱,种植地点或许是位于其永久定居点。[25][70]

近现代

相比罗马时期,中世纪欧洲人更注重农业的自给自足。农业人口在封建制度下组织成大型庄园,这些庄园通常有上百英亩土地,土地所有者一般是罗马天主教会及其牧师。[71]得益于阿拉伯农业革命成果传播,欧洲农业获取了许多新的技术,并引入了新的栽培物种,稻米、棉花和果树。[72]

15世纪哥伦布发现美洲后,旧大陆与新大陆之间交换了大量农业产品,美洲大陆的玉米、马铃薯、番茄、番薯、木薯等作物传入欧洲,而旧世界的小麦、大麦、稻米、芜菁等作物,以及马、牛、绵羊、山羊等牲畜传入新大陆。[73]

自17世纪英国农业革命后,灌溉、轮作、化肥技术的发展促使世界人口快速增长。而自20世纪以来,发达国家逐渐以机械自动化装置取代农业中的人工劳作,并利用合成肥料、杀虫剂和选择育种协助农业工作。德国化学家弗里茨·哈伯提出的哈伯法可大量生产硝酸铵,其作为一种重要的肥料,极大提高了农业产量,促进20世纪人口的迅速增长。[74][75]不过,现代农业也引发了许多生态环境、政治、经济相关议题,例如水污染、生物燃料、转基因作物、关税、农业补贴等,这些问题促使人们开始关注有机农业。[76][77]

类型

游牧是畜牧的一种形式,牧民依据不同时间草场、饲料和水源变化,定期迁徙牧群。这种农业形式主要分布在撒哈拉干旱与半干旱地区、中亚,以及印度部分区域。[78]

轮耕是作物种植的一种形式。农民首先从森林中开辟一块土地,在此种植作物,在数年后肥力过低时将其废弃。而后农民会选择另一块林地重复上述过程。这种种植方式主要流行于印度东北部、东南亚、亚马孙盆地的热带雨林地区,因为这些区域的土地可在废弃后快速再生为森林。[79]

自给农业是指仅为满足家庭或本地需求的农业活动,很少有多余的产品运输至其他地区。自给农业在亚洲季风区和东南亚十分常见[80],截至2018年,世界上大约有25亿人从事自给农业,其耕地面积占总耕地面积约60%。[81]

集约农业是指以最大化产量为目的的农业活动,尽可能的减少休耕期,并有大量资源投入(水、化肥、杀虫剂和自动化装置)。这类农业主要分布在发达国家。[82][83]

当代农业

现状

自20世纪以来,集约农业大量提高了粮食产量。如今,小型农场的食物产出约占世界总量的三分之一,但大型农场正变得十分普遍。占据前1%大小的农场平均面积超过50公顷,所管理的土地面积占所有耕地面积70%。将近40%的耕地属于面积超过1,000公顷的巨型农场。不过,六分之五的农场面积仍小于2公顷。[84]化肥和杀虫剂等化学产品有助于农业产出,却也造成了水污染问题。如今,农业面临的主要问题是土壤退化与植物疾病(例如秆锈病)[85],世界上大约40%的耕地已严重退化。[86][87]鉴于传统农业带来的诸多环境问题,人们开始寻找替代方法,例如有机农业、可再生农业或是永续农业。[76][88]欧盟是农业改革的主要推动者,它于1991年开始认证有机食品,并在2005年修改了共同农业政策,取消了农业补贴与特定商业作物的联络。[89]有机农业的发展也促成了一些旧有研究领域的复兴,例如综合虫害管理、选择育种[90]、控制环境农业。[91][92]然而,也有人担忧有机农业相对较低的产量可能会危机全球粮食安全。[93]与此相关的科学研究包括转基因食品的生产制作。[94]

截至2015年,中华人民共和国的农业产出居世界首位,其次是欧盟、印度和美国。[95]经济学家估算如今美国农业的全要素生产率约为1948年的1.7倍。[96]

尽管现代农业已大大进步[97],但截至2021年仍有7.02-8.28亿人受饥饿威胁。[98]影响粮食安全的因素包括战乱冲突、气候变化与极端天气、经济波动[97],也可能源自国家结构特征(例如收入水平)、自然资源丰富程度、政治经济制度等。[97]国际农业发展基金认为,增加小产权农户的比重或许是解决粮食价格问题,并缓解粮食安全忧虑的可行方案,这种方法已在越南实行且成果甚佳。[99]

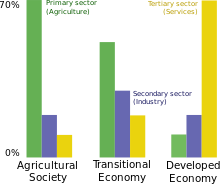

劳动力

农业提供了全球大约四分之一的劳动岗位,撒哈拉以南非洲有超过一半的人口从事农业,而在部分低收入国家这一比例甚至超过60%。[100]随着社会发展,许多农业人口会转向其它行业,而新技术的运用也允许农业在降低劳动力的情况下维持充足产量。[101][102][103]随时间推移,从事农业的人口比例会逐步降低。[104]

在16世纪的欧洲,大约有55-75%的人口从事农业,而到了19世纪,则下降至35-65%。[105]如今,这些国家的农业人口低于10%。[106]在20世纪初,全世界有约三分之一的人口从事农业,总人数大约10亿人。这占到全球儿童劳动力的70%,农业在许多国家也是女性从业比例最高的行业。[107]从2007年起,服务业取代了农业成为全球从业人口最多的行业。[108]

在许多发达国家,外来移民填补了农业中难以机械化的岗位。[109]2013年,来自东欧、北非和南亚的农场工人占西班牙、意大利、希腊和葡萄牙所有农业雇员的三分之一。[110][111][112][113]而在2019年的美国,超过一半(大约45万)农业雇员为移民者,不过近年来新移民从事农业的比例已下降了75%,由此导致了美国农业的劳动力短缺。[114][115]

纵观全球,女性在农业中占据重要部分。[116]在除东亚和东南亚以外的发展中国家中,农业劳动力中的女性比例已接近50%。[116]在撒哈拉以南非洲,女性占47%的总农业劳动力,这个数字在过去数十年间没有显著变化。[116]不过,联合国粮食及农业组织认为女性在农业中的角色可能正发生变化,例如从小型家庭农场劳动力变为雇佣员工,或因男性外出就业而从家庭合作劳动者转变家庭中主要的生产者。[116]

安全风险

农业,尤其是耕作行业仍是较为危险的行业,世界范围内的农民都有较高的工作相关受伤风险,这些伤病包括肺部疾病、噪音造成的听力损伤、皮肤疾病,以及暴露在特定化学产品中的风险。在工业化农场中,从业者也可能在使用农业机械时受伤,在发达国家,农用拖拉机翻车事故是导致农业致命伤害的常见原因。[117]杀虫剂等化学产品可能会对接触者造成危害,长期暴露在这些产品中可能会引发疾病或增加新生儿致畸风险。[118]工业化农场从业者常是整个家庭一同居住在农场,从而增加家庭成员的受伤和罹患疾病风险。[119]家庭中6岁以下儿童尤其可能遭受农业伤害[120],常见的事故原因包括溺水、机械或引擎事故、农用车辆侧翻等。[119][120][121]

国际劳工组织将农业认定为“所有经济行业中最具危险性的行业之一”。[122]它认为每年与农业劳动相关的死亡至少有17万,死亡率是其它行业平均值的两倍。此外,农业相关伤病也十分常见,但通常不被记录。[122]该组织于2001年制定了《农业安全与健康公约》,其中覆盖了农业领域可能包含的安全风险,对这些风险的预防方法,以及个人和组织在农业活动中应当发挥的作用。[122]

美国国家职业安全卫生研究所将农业置于职业安全研究的优先位置,为其中存在的安全与健康风险提供干预策略。[123][124]欧盟职业安全卫生局也制定了准则以保护农业、畜牧业、园艺、林业从业者的健康与安全。[125]美国农业安全与健康委员会(The Agricultural Safety and Health Council of America)每年都会组织会议,邀请各界专家与政策制定者探讨该行业的安全问题。[126]

农业生产

|

参见:各国各产业国内生产总值列表和产值最高的农作物和牲畜产品列表 |

世界上农业总产值最高的国家如下:

| 根据国际货币基金组织和CIA《世界概况》的数据得出的2018年农业总产值(名义值[a])排名 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 联合国贸易和发展会议以2005年固定价格与汇率为基础,列出的2015年世界最大农业生产国排名[127] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

作物种植

作物种植产出受多种因素影响,例如当地自然资源与环境限制、农场的地理与气候条件、农业政策、社会经济环境、农业文化等。[128][129]

轮耕,或称烧荒农业,是指农民通过在森林中放火烧出一片供农业耕作的土地,这片土地的肥力可维持数年。[130]待肥力降低后,这片土地即被遗弃,让其重新成长为森林,而农民转向其它林地重复开荒过程,直到一段时间(10-20年)后再次对其开垦。如果当地人口密度较高,就需要借助一些额外手段,例如使用化肥或控制害虫,以减少休耕间隔。而年耕是一种强度更高的耕作方式,几乎不存在休耕期,这种方法需要向土地添加大量养分并维持害虫控制。[130]

随工业化发展,农业发展出了单一耕作方式,即在大面积土地上种植同种作物。由于缺乏生物多样性,养分使用也相对单一,病虫害的问题更加严重,导致杀虫剂和化肥的需求增加。[129]与此相对,复作或混养是指多种作物在一年中依顺序种植,同时保持其它作物的间种和伴生种植。[130]

在亚热带和干旱环境,农业种植受降雨限制,可能无法在同一年内多次种植一年生作物,或是需要额外的灌溉。这些气候环境可支持多年生作物生长,例如咖啡、可可等,并可实践混农林业。在温带环境,生态系统多为草地和草原,在这些区域主要为高产量的年耕。[130]

农业中重要的食用作物包括谷物、蔬菜、草料、水果和豆类。[131]自然纤维来源包括棉花、羊毛、火麻、丝绸和亚麻。[132]不同作物在全球不同区域种植。根据联合国粮农组织的估算,全世界农业产出如下表[131]:

| 根据农业产品种类计算的产出 (单位:百万吨)2004年数据 | |

|---|---|

| 谷物 | 2,264 |

| 蔬菜和瓜类 | 866 |

| 根类和块茎类 | 715 |

| 乳类 | 619 |

| 水果 | 503 |

| 肉类 | 259 |

| 植物油 | 133 |

| 鱼类(2001年数据) | 130 |

| 蛋类 | 63 |

| 豆类 | 60 |

| 纤维类 | 30 |

| 来源: 联合国粮农组织[131] | |

| 根据作物物种计算的农业产出 (单位:百万吨),2011年数据 | |

|---|---|

| 甘蔗 | 1794 |

| 玉米 | 883 |

| 水稻 | 722 |

| 小麦 | 704 |

| 马铃薯 | 374 |

| 甜菜 | 271 |

| 大豆 | 260 |

| 木薯 | 252 |

| 番茄 | 159 |

| 大麦 | 134 |

| 来源: 联合国粮农组织[131] | |

畜牧生产

|

参见:驯化动物列表 |

畜牧业是指养殖动物以获取肉类、奶制品、蛋类或毛发,或是作为替代劳动力的活动。[133]役畜包括马、骡、阉公牛、水牛、骆驼、大羊驼、羊驼、驴、狗等,它们可帮助人类耕作土地、驮运货物、管理其它家畜。[134]

畜牧系统根据饲料来源可分为草地、混合和无土地三类。[135]截至2010年,地球除水域和冰雪覆盖之外的土地中,有大约30%被用于动物养殖,全球有约13亿人从事畜牧业。自1960年代至21世纪初,家畜数量和平均肉类产出,尤其是猪、牛、鸡这三类家畜的产量都有了大幅增长,其中鸡的产量增加了近10倍。非产肉动物产量,例如奶牛、蛋鸡等也有显著的增长。至2050年,全球范围内牛、绵羊、山羊的数量预计将持续增加。[136]封闭场所中的渔业养殖也有显著增长,1975-2007年的年均增长率为7.9%。[137]

20世纪后半叶,畜牧业开始大量应用动物选择配种和杂交方法,这些方法显著提升了产量,但同时也造成了养殖动物遗传多样性降低,由此导致家养动物进化出的适应性与抗病性减弱。[138]

草地畜牧业需要依靠灌木、草原或牧地放养草食动物,动物粪便可作为肥料排放回这些区域。部分区域因气候或土壤限制而难以施行农耕,因此草地畜牧业是这些地区主要的农业活动方式,全世界大约有3,000-4,000万牧民。[130]混合畜牧业使用草地放养动物,但也辅以草料或粮食作为反刍和单胃动物(主要是牛和鸡)的饲料。在这种畜牧系统中,动物粪便会被回收作为作物的肥料。[135]

无土地畜牧业使用农场外的食物饲养动物,这种饲养方法在经济合作与发展组织成员国(主要为发达国家)中较为常见,其标志着作物与畜牧生产的分离。全球大部分猪肉和家禽都由无土地畜牧方式生产。据估计,2003-2030年约75%的家畜在室内封闭环境饲养,这种饲养方式也称为工业养殖。[136]部分商业养殖会采用生长激素促进动物生长,这种养殖方法存在许多争议。[139]

方法与实践

耕作是使用工具(例如犁或耖)在作物种植前翻土,以将营养物质混入土壤或控制虫害的过程。传统农业中,耕作需要耗费大量人力。翻动土壤可提高土壤温度,扩大化肥和杀虫剂的作用范围,进而增加农业产量。然而,耕作也会加速土壤侵蚀,促使土壤有机质分解,并减少土壤的生物多样性。现代免耕农业提出了不使用耕作而直接种植作物的方法,这种方法不仅减少了人力投入,同时还可以减少土壤侵蚀,保留更多的有机质。[140][141]

农业有害生物包括杂草、昆虫、螨虫、病原体等对作物生长造成不利影响的生物。针对这些有害生物,常见的控制措施包含化学控制(例如使用杀虫剂)、生物防治、物理防治(例如耕作)。此外,人们也采用轮作、农业淘汰、覆土作物、间作、堆肥、抗病性筛选等农业实践防止害虫。综合虫害管理(IPM)致力于集成上述所有方法,将有害生物对农业造成的经济损失控制在较低水平,而杀虫剂则作为这些方法无效时的最后手段。[142]

营养管理是指对作物和牲畜的营养投入,以及牲畜粪肥管理。营养投入包括非生物化肥、粪肥、绿肥、堆肥和矿物质等。[143]作物营养管理也包括轮作与休耕的安排。动物产出的粪肥可用于辅助草料生长,例如应用在集约化轮牧草场,或以液态或固态形式撒布于农田或放牧场中。[140][144]

在气候多变或降水稀缺的地区,水资源管理显得尤为重要。[130]一些农场在自然降雨之外也给作物补充额外水分,这种行为称为灌溉。在一些特定区域(例如北美大平原),农民会采取休耕一年的方式,让土壤获得足够未来数年耕种所需的水分。[145]现代精确农业可以更加便利地监控和调配水资源,从而提高水资源的管理效率。[146]全球约70%的淡水用于农业生产[147],这个比例在各个国家之间存在明显的差异。低收入国家和内陆国家的农业取水率可达90%,而在小岛屿发展中国家,取水率约为60%。[148]

国际食物政策研究所在2014年的研究报告中指出,现代科技与农业的结合可在未来显著提高食物产量。该报告利用预测模型了11项新兴科技在农业产出、粮食安全和贸易方面的影响。报告指出,2050年面临饥饿的人口将减少40%,同时粮食价格也将降至目前水平的一半。[149]

生态系统服务功能补偿是针对农民或土地所有者的激励措施,鼓励他们提供生态系统服务,例如水资源管理、碳固定、生物多样性维护等。通过收集补偿基金,这些计划还可以用于在城市河流上游进行重新植树造林,从而改善淡水供应。[150]

农业自动化

农业自动化多种不同定义。其中一种定义认为,自动化是指机械装置在没有人类干预的情况下自动执行任务。[151]而另一种定义认为,自动化是借由便捷、自主、拥有决策能力的机械电子装置的辅助完成各类生产任务。[152]不过,联合国粮农组织也指出,上述定义并不能涵盖所有的自动化农业形式。例如场所固定的挤奶机,自动执行农业操作的机械装置,以及只为排错目的设置的电子工具(例如各类传感器)。[146]因此,联合国粮农组织将农业自动化定义为在农业活动中使用机械装置提高排错、决策或执行效率,减轻农业操作的繁琐程度,提高及时性和潜在精度。[153]

农业技术发展经历了从人力工具、动物牵引、机械化、电子化,最终到人工智慧机器人的转变。[153]机械化装置使用引擎驱动,可代替农业中的重复人力操作,如耕地和挤奶。[154]随着数字自动化技术发展,这些机械也被赋予了自动排错和自主决策的能力。[153]例如,谷物收割机器人可自主完成收割谷物并播种,而无人机可采集资讯以提高自动化的准确性。[146]这些自动化机械在现代精准农业中十分常见。[146]如今,传统机械装置正被附带排错与决策功能的数码化装置取代[154],例如过去农业中常用的拖拉机现在正逐渐被新型农用车辆所替代,这些车辆可自动在农田中播种。[154]

自动化装置也被广泛应用在畜牧管理中。根据市场数据,自动化产奶系统的销量在最近数年有显著增加[155],不过,该技术主要应用于北欧国家[156],在中低收入国家应用较少。市场上也存在针对奶牛和家禽的自动喂料系统,但关于这类系统的销量趋势数据较少。[157][146]

关于农业自动化对就业影响的研究较为困难,因为这类研究需要收集农业上下游产业工人的大量跟踪数据。[153]自动化引发某产业工作岗位减少的同时也会增加其它产业的工作岗位,例如农业自动化减少了部分农民的工作必要性,但同时增加了新的就业岗位,例如农业机械的操作与维护。[146]农业自动化也激励了生产者扩大生产规模,并创造其它农业系统,由此刺激就业增长。[158]在部分高收入和中等收入国家,自动化可填补农村地区日益短缺的劳动力。[158]但如果在农村劳动人口充裕的情况下,政府采用补贴的形式强制推广自动化装置,就可能引发失业浪潮,或导致薪资停滞或下降,这对穷困和低技能劳工的影响尤为明显。[158]

气候变化影响

|

主条目:[[:气候变化对农业的影响]] |

农业与全球范围内的气候变化紧密相关。全球变暖改变了四季均温、降水、并引发极端天气(例如风暴和热浪);影响作物疾病和昆虫活动;改变大气二氧化碳和地表臭氧浓度;改变部分食物的营养价值[159];导致海平面上升。[160]全球变暖已对各地农业造成影响,影响程度因地理位置不同而有差异。[161]未来的气候变化可能导致低纬度地区粮食产量降低,而对北纬地区的影响可能混合有积极与消极影响。[161]这些影响可能危及部分弱势群体(例如穷人)的粮食安全。[162]

生物技术

植物配种

|

主条目:植物配种 |

人类通过配种来筛选植物理想性状的实践已有数千年历史。在作物后代选育的过程中,一些特定的性状被保留并得到了增强,例如更大的果实、抗旱抗虫性等。得益于19世纪奥地利生物学家孟德尔关于显隐性基因的研究,人类对植物遗传和配种有了更深入的理解,致使植物配种技术的进展颇为可观。作物配种方法包括筛选理想性状、自花传粉、异花传粉,以及在分子层面修改遗传基因。[163]

在过去几个世纪,驯化作物的产量显著增加,抗旱与抗虫性提升,并更易于收割,营养价值也有提升。1950年代,在X射线和紫外线诱变技术的帮助下,诞生了首批现代商业作物,例如小麦、玉米和大麦的特殊物种。[164][165]

20世纪中叶的绿色革命促进了作物杂交种的普及,由此创造的“高产品种”极大提升了粮食产量。例如,美国在20世纪初的玉米产量为每公顷2.5吨,到21世纪初则提升到每公顷9.4吨。世界范围内小麦产量也从20世纪初的每公顷1吨,提升到20世纪90年代的每公顷2.5吨。其中南美洲平均小麦产量为每公顷2吨,非洲不到每公顷1吨,埃及和阿拉伯在灌溉下可达到每公顷3.5-4吨,而法国每公顷甚至超过8吨。上述产量差距源于气候、作物基因和农业技术的差异,其中技术差异包括化肥和杀虫剂的使用,生长控制避免倒伏等。[166][167][168]

基因工程

基因改造生物是指由基因重组技术而被修改遗传材料的生物体。基因工程扩大了育种者可选择的范围,作物可借这项技术获得更强的环境耐性,更高的营养价值,抗病与抗虫性,对除草剂的抗性等。[169]不过,基因改造生物也引发了部分群体的担忧,有人认为这些作物可能存在未知的安全问题。一些国家限制基因改造生物的生产或进口[170],国际协定《卡塔黑纳生物安全议定书》也限制了这类产品的贸易。各地关于转基因食品的标签有不同规定,例如欧盟要求转基因食品必须有标注,而美国则没有这类要求。[171]

抗除草剂作物是经基因改造,可暴露于除草剂(例如草甘膦)而正常生长的作物。农民在种植这类作物时可使用除草剂控制田间杂草,而不必担心危害作物的生长,由此提升作物产量。随着这类作物在全球范围的广泛种植[172],农民对草甘膦除草喷雾的使用也有增加。研究发现,在一些地区已出现具有草甘膦抗性的杂草,这促使农民选择其它种类的除草剂。[173][174]还有一些研究指出,草甘膦的普遍使用可能导致了部分作物铁元素的缺乏,这引发了关于这类作物产量和营养质量的忧虑。[175]

农业中使用的基因改造生物还包括抗虫作物,这类作物的抗虫基因来源于土壤细菌苏云金芽孢杆菌(Bt),其可产生对昆虫而言有毒的化合物,从而抵抗虫害。[176]也有人认为,借助传统植物配种技术也可获得与转基因类似的抗虫性状,并可透过与野生物种的杂交或异化传粉获得对多种害虫的抗性。在部分情况下,野生物种是作物抗性的主要来源,例如一些番茄品种借助于野生番茄的杂交而获得了针对至少19种疾病的抗性。[177]

环境影响

|

主条目:农业对环境的影响 |

影响与损失

农业即是环境退化的原因,也深受其影响。诸如生物多样性丧失、荒漠化、土壤退化、全球变暖等都会降低农业产出。[178]农业是环境压力的主要驱动者,不当的农业活动可能造成栖息地破坏、气候变化、水的过度消耗和污染。人类释放到环境中的有毒物质主要源自农业活动,这些物质包括杀虫剂,尤其是用于棉花的杀虫剂。[179][180]联合国环境署在2011年的绿色报告中表示,农业活动产生的温室气体占人类总排放的13%,这些温室气体来源于无机化肥、农药杀虫剂、除草剂,以及活动中消耗的化石燃料。[181]

上述环境影响带来的损失包括化学物质对自然环境的伤害、营养流失、水资源浪费,以及生态环境破坏。根据2000年的一项估计,英国在1996年因农业造成的经济损失约为134.3亿英镑,相当于每公顷土地损失208英镑。[182]而根据另一项2005年的分析,美国因农业种植造成的经济损失约为50-160亿美元,约合每公顷30-96美元,而畜牧业造成的损失则为7.14亿美元。[183]这两项研究都关注了农业造成的外部成本,并认为有必要将这些成本内化,以更好地衡量其真实的社会与环境成本。这两项分析研究都未将农业补贴考虑在内,但它们也提到农业补贴也可对农业活动的社会成本造成影响。[182][183]

现代农业致力于增加产量并减少支出。增加产量的方法包括使用化肥,以及应用各类手段去除作物病原体、捕食者和竞争者(例如杂草)。这些措施的平均花费随农田面积扩增而降低,因此现代农业倾向于扩大农田面积,从而移除树篱、沟渠,以及其它生物的栖息地,并使用农药消灭昆虫、杂草和真菌。在集约农业中,大面积农田仅种植十分有限的作物,由此导致环境中的生物多样性处于极低水平。[184]此外,农业产出还可能因为农产品收割、处理或加工时的操作而导致额外损失。[185]

因为气候变化,过去某地罕见的有害生物与疾病可能会变得流行。例如在法国香槟地区,农民发现了当地小麦患上了秆锈病,这类疾病只在20-30年前的摩洛哥曾有出现。气候变化影响了冬季均温,因此在过去无法活过冬季的昆虫如今却可能可以存活甚至正常繁衍。[186][187]

畜牧业环境问题

联合国高级官员亨宁·斯坦菲尔德曾表示,畜牧驯养是引发环境问题的最主要因素之一。[188]畜牧业用地占农业总用地面积的70%,或占总陆地面积30%。其为最主要的温室气体排放源头,占全球总排放的18%,相比之下,所有交通工具的温室气体排放只占总排放的13.5%。畜牧业还产生了大量一氧化二氮气体,占总排放的65%,这类气体的暖化效应是二氧化碳的296倍,此外也产生了37%的甲烷、64%的氨。畜牧业扩张被认为是造成森林砍伐的主要原因。亚马孙盆地中70%被砍伐的森林转变为了牧场,剩余的也被用作种植饲料,[189]生物多样性也受此影响。根据联合国环境署的声明,如果依照当前的增长趋势,至2030年全球甲烷排放将增长60%。[181]

土地与水资源问题

|

参见:灌溉的环境影响 |

人类对土地的转化,也即把自然土地转变为农业生产服务用地,可对地球生态系统造成巨大影响,并引发生物多样性丧失。据估算,被人类转化为农业用地的土地约占地球总土地面积的39-50%。[190]而土地退化,即土地长期生态功能和生产力的降低,因作物过度种植而发生在全球24%的土地。[191]有15亿人依赖退化土地生存,造成退化的原因有森林砍伐、荒漠化、土壤侵蚀、矿物质枯竭、土壤酸化和盐碱化等。[130]

农业活动可能造成水域生态系统富营养化,从而引致水华或消耗水体氧气,导致鱼类死亡、生物多样性丧失,受污染水体也不再适合饮用或工业用途。种植土地上过度使用化肥与粪肥,或过高密度的畜牧业可造成养分随地表径流流入水体,这些污染物属于非点源污染,是导致水域生态系统富营养化和地下水污染的主要因素。[192]化肥的过度使用也会让陆地上部分物种获得过度生存优势,从而导致生物多样性降低。[193]

如今,农业面临着不断增长的淡水需求,以及降水异常(干旱、水涝、极端天气等)问题。[12]大约70%淡水资源取用与农业相关[194][195],41%的灌溉水资源影响到了环境水流需求(environmental flow requirements)。[12]很久以前人们就注意到在部分区域,例如中国北部、印度的恒河上游,以及美国西部的含水层正在枯竭,而2012年的研究指出,这种状况已在越来越多地区出现。[196]农业需要生产更多粮食,以供应全球日益增长的人口,但由人工增长带来的工业与城市发展同时也占据了农业所需的部分水资源,因此节水是未来农业发展的一个重要方向。[197]虽然工业取水量在过去数十年有所下降,城市取水量自2010年来仅略有增长,但农业取水量却正以前所未有的速度增长。[12]农业用水也可造成许多环境问题,例如湿地破坏、水媒传染病流行,以及因错误灌溉导致的土地盐碱化或内涝。[198]

杀虫剂使用

|

主条目:杀虫剂的环境影响 |

自1950年代起,杀虫剂的使用日益增多,如今年度使用量已达到230万吨。然而,杀虫剂的广泛使用并未显著减少害虫对农业造成的损失。[199]根据1992年世界卫生组织的估计,全球每年有300万人因杀虫剂中毒,由此致死的人数高达22万。[200]此外,由于杀虫剂的广泛使用,部分害虫已经产生了对杀虫剂的抗性。为对抗这种抗性,人们不得不进行“杀虫剂军备竞赛”,也即持续地开发新型杀虫剂。[201]

另一个与杀虫剂相关的有争议的话题是,集约农业推行者主张该农业方式可以在有限的土地上通过大量使用杀虫剂以及高成本单位投入,将粮食产量最大化,以解决饥荒问题。正如全球食品问题中心在其网站上所说:“在每公顷土地上种植更多作物,为自然留出更多空间”。[202][203]然而,有批评指出,粮食安全与环境保护的冲突并非不可避免[204],并且杀虫剂的使用也会淘汰传统遗留的良好农业方法,例如轮作。[201]有人提出推力-拉力害虫控制策略,借助作物间种方式,利用部分植物的特殊气味驱赶害虫(推力),并将其引诱至方便移除的位置(拉力)。[205]

气候变化

|

主条目:来自农业的温室气体排放 |

农业活动对气候变化的影响主要包括温室气体排放与森林砍伐。[206]农业、林业和其它土地使用活动产生的温室气体占人类总排放的13-21%。[207]农业产生的温室气体中,超过一半为一氧化二氮和甲烷。[208]畜牧业是农业温室气体的主要来源。[209]

在所有农业温室气体中,57%与动物食物生产相关,29%与植物食物生产相关。作物种植领域温室气体排放最多的是水稻生产(占12%),而动物制品中温室气体排放最高的是牛肉生产(占25%)。南亚、东南亚和南美是生产型温室气体的最大排放区域。[210]

可持续性

|

主条目:可持续农业 |

由于水资源短缺、土壤侵蚀和肥力降低等因素的影响,现行的农业实践已不可持续。因此,必须重新考虑农业生产与水、土地和生态系统之间的关系。其中一个解决方向是赋予生态系统实际价值,认识农业生产活动消耗的生态成本,并平衡各方利益。[211]但是,这些措施也可能会导致不平等,例如水资源的分配失衡(富裕群体获得更多资源)、将土地强制转化为更具生产力的农业活动、或保护湿地而限制渔业权利等问题。[212]

现代科技创新有助于实现农业的可持续性。[213]例如,采用保护耕作技术可以显著减缓土壤侵蚀速率、降低水污染、增强碳截存能力。[214]农业自动化技术可以帮助农业应对气候变化影响,提高农业的适应能力。[146]数字自动化技术(如精确农业)可以提高资源利用效率,使农民能够在不适宜的环境中进行生产活动。[146]此外,传感器和预警装置的部署可以降低气候变化导致的极端天气事件对农业的影响。[146]

其它增加农业可持续性的措施还包括应用保护性农业、混农林业、改善畜牧业、避免草地转换、使用生物炭等。[215][216]目前在美国等发达国家大量运用了单一作物种植,它取代了以往农业中的可持续耕作实践,例如每年两到三次作物轮作,包括干草和农作物的混种。在农业政策中增加土壤碳截存等减排目标或许可以促进这类农业实践向可持续耕作方法转变。[217]

根据当前全球人口增长速度和气候变化趋势,农业仍有望通过更新方法、扩大耕地面积和减少消费浪费等方式满足人类粮食需求。[218]

能源消耗

自20世纪40年代以来,机械化的广泛应用以及化肥和杀虫剂产业的发展使全球农业产量有了大幅增长。[219]1960年代至1980年代的绿色革命将农业技术推广到全球各地,使农业产量进一步增长(不同地区小麦产量增长60%至390%,水稻产量增长60%至150%)[220],全球人口数量翻了一倍。但是,对化石燃料的过度依赖也引发了部分人对未来能源短缺的担忧,这可能会增加农业成本并影响农业产出。[221]

现代农业中的能源消耗主要可以分为两个方面:直接消耗和间接消耗。直接能源消耗包括农用机械所需的燃料和日常维护所需的润滑剂。[221]间接能源消耗则包括生产化肥、杀虫剂和农用机械所耗费的能源。[221]其中,生产氮肥消耗的能源占农业总能耗一半以上。[222]农业的能源消耗被包括在食品产业的能源消耗中,除了农业,食品产业的能源消耗还包括食品的处理、运输、包装和销售等环节。农业在食品产业能源消耗中的比例并不高,例如在美国,农业占食品产业能源消耗的比例约为五分之一。[223][224]

塑料污染

|

主条目:塑料污染和农用塑料 |

塑料在农业中应用广泛,用途包括增加作物产量,优化水资源和化学产品利用率。常见的农业塑料产品包括:覆盖温室的塑料薄膜、覆盖土壤的地膜(用于抑制杂草生长、保水保温、增加肥料利用率)、遮光材料、杀虫剂包装、育苗盆、保护网和灌溉管道等。这些塑料产品的主要成分包括低密度聚乙烯(LPDE)、线性低密度聚乙烯(LLDPE)、聚丙烯(PP)和聚氯乙烯(PVC)。[225]

农业中使用的塑料产品总量难以估计。一项2012年的研究表明,全球每年使用的塑料总量约为650万吨,预计到2015年,这个数字将增加至730-900万吨。农业中大量使用地膜,即用于覆盖土壤的塑料薄膜。这些塑料因天气影响而快速老化,最终会分解成微小碎片混入自然环境。这些塑料碎片可能在土壤中堆积,有研究表明每公顷土地中的薄膜碎片可能多达50-260千克,其中许多已存在于土壤中十多年。这些塑料是环境中大颗粒塑料和塑料微粒的主要来源。[225]

农业中广泛使用的塑料(尤其是塑料薄膜)通常难以回收,因为这些材料受污染严重,其中有40-50%被杀虫剂、化肥、土壤碎屑、潮湿的植被、青贮污水、紫外线吸收剂等污染。因此,农业塑料产品通常被掩埋、遗弃在田地或河道中,或直接焚毁。这些处理方式会导致土壤退化和污染,微塑料可能会随河流或潮水冲入海洋环境。塑料薄膜上的附着物(例如紫外线和热量吸收剂)可能会影响作物生长、破坏土壤结构,影响营养转运和盐分平衡。土壤中的塑料也会阻碍土壤的吸水能力,增加温室气体排放。微塑料会随食物链逐步积聚在生物体内。[225]

农业政策

|

主条目:农业政策 |

| 产品 | 补贴

(单位:10亿美元) |

|---|---|

| 牛肉 | 18.0 |

| 牛奶 | 15.3 |

| 猪肉 | 7.3 |

| 禽类 | 6.5 |

| 大豆 | 2.3 |

| 鸡蛋 | 1.5 |

| 绵羊 | 1.1 |

农业政策是指政府制定的与农业生产和国外农产品进口相关的政策。政府通常会以国内农业市场的特定预期目标来制定农业政策,这些目标的涉及范围十分广泛,例如:风险管理与调整(包括与气候变化、粮食安全、自然灾害相关的政策);经济稳定性(包括税收政策);自然资源和环境的可持续性(例如水资源相关政策);科学研究与发展;国内商品的市场准入(包括与国际组织的关系和与他国的协定)。[227]农业政策也可能涉及食物质量,也即保证食物供应的质量和稳定性;粮食安全,保证食物供应可满足人口需求;以及自然保护。政策实施方式可能涉及财政项目,例如农业补贴。[228]

根据2021年的一份研究报告,全球每年向农业生产者的支持与补助高达5,400亿美元,占农业总产出价值的15%。[229]这些补助有明显的偏向性,可能促使效率低下、分配不均,或支持可能危害环境和人类健康的活动。[229]

农业政策的制定受多方面影响,包括消费者、农业生产者、农企业、贸易游说团体等。其中农企业通过游说和政治捐赠等方式对政策制定具有巨大的影响力。此外,政治行动团体也会对农业政策施加影响,例如环境问题或工会利益等话题都会影响农业政策的制定。[230]联合国粮食及农业组织动物产品与健康部门主任塞缪尔·尤茨曾表示,大企业的游说阻止了有利于维护人类健康和自然环境的政策。例如2010年有关畜牧业自愿准则的提议,这些准则旨在提供畜牧业中的健康与环境监管要求,比如在一特定区域内可饲养多少动物而不至引发长期危害,然而该提议因来自大型食品公司的压力而被中止。[231]

农业学科

农业经济学

|

主条目:农业经济学 |

农业经济学是一门应用经济学,关注农业产品与服务的生产、分配和销售。[232]该学科始于19世纪末,是农业和市场经济学的结合,自20世纪开始得到广泛应用。[233]尽管这门学科相对较新,但历史上农业对于国家和国际经济的一直都有重大影响,从美国内战后的南方的佃农[234],到欧洲的封建庄园经济[235],这些都可以从农业经济学的视角得到解释。粮食的处理、分配和农业营销称为“价值链”,相比过去,这些成本有所上升,而农业生产成本却在下降。其原因在于农业产品加工的复杂性增加(也即更高的附加价值),以及农业生产效率的提高。农业市场集中度也在增加。更加集中的市场有助于提高效率,并导致经济剩余在生产者(农民)和消费者之间的再分配,但也可能对乡村社区产生负面影响。[236]

政府施行的各种政策,如税收、补助、关税等,可对农产品市场产生显著影响。[237]自20世纪60年代以来,贸易壁垒、汇率制度和农业补贴的综合作用对全球农民产生了深远影响。在20世纪80年代,由于农业补贴导致的人为降低农产品价格,为无补贴的发展中国家农民带来了不利影响。从1980年代中期到21世纪初,一些国际协议对农业关税、补贴和其他贸易限制作出了约束。[238]

尽管如此,直到2009年,全球农产品价格仍受诸多政策因素影响而出现扭曲。受贸易限制影响最大的三种农产品分别时糖、牛奶和大米,限制主要来自税收政策。在油籽作物中,芝麻的税收最高,但总体而言畜牧产品的税收远高于饲料和油籽作物。自20世纪80年代以来,由政策导致的畜牧产品价格扭曲已大幅减少。[237]然而,一些作物如棉花在部分发达国家仍受到补贴支持,导致价格人为压低,这为发展中国家没有补贴的农民带来了负面影响。[239]未加工产品如玉米、大豆、牛肉等,它们可能会根据质量进行分级,从而影响销售价格。[240]

农业科学

|

主条目:农业科学 |

|

更多信息:农学 |

农业科学是一门跨学科的领域,涉及自然科学、经济学和社会科学等相关理论,应用于农业研究与实践中。该领域的研究主题包括农艺学、植物育种、遗传学、植物病理学、作物模式建构、土壤科学、昆虫学、生产技术改良、虫害控制管理,以及环境相关研究,如土壤退化、水资源管理、生物修复等。[241][242]

对农业的科学研究始于18世纪,约翰·弗里德里希·迈耶透过实验证明了施用石膏(水合硫酸钙)作为化肥对农业的助益。[243][244]1843年,约翰·班纳特·劳斯和亨利·吉尔伯特(Henry Gilbert)开始在英国洛桑研究所展开一系列长期农田试验,这些试验标志着农业科学研究开始走向系统化。部分试验,例如公园草地试验,甚至直到今天仍在运作。[245][246]在美国,随着农民对化肥日益增长的兴趣,1887年哈奇法案首次为全新的学科"农业科学"提供了资金。昆虫学领域,美国农业部从1881年开始研究害虫生物防治,并在1905年开始首个大型项目:从欧洲和日本找寻欧洲舞毒蛾和茶毒蛾的自然天敌,将这两种害虫的寄生蜂(例如栖蜂)和自然天敌引入美国。[247][248][249]

参考文献

注释

- ^ 名义价值是指该数据并未考虑通货膨胀或汇率的影响,而是以原始的货币单位进行衡量。

脚注

- ^ The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. Making agrifood systems more resilient to shocks and stresses. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2021 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-92-5-134329-6. S2CID 244548456. doi:10.4060/cb4476en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ FAOSTAT. New Food Balance Sheets. FAO. [2021-07-12]. (原始内容存档于2011-07-13).

- ^ Discover Natural Fibres Initiative – DNFI.org. dnfi.org. [2023-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2023-04-10).

- ^ FAOSTAT. Forestry Production and Trade. FAO. [2021-07-12]. (原始内容存档于2011-07-13).

- ^ In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2019 [2023-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-03).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Definition of Agriculture. State of Maine. [2013-05-06]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-23).

- ^ Herren, R.V. Science of Animal Agriculture. Cengage Learning. 2012 [2022-05-01]. ISBN 978-1-133-41722-4. (原始内容存档于2022-05-31).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Larson, G.; Piperno, D. R.; Allaby, R. G.; Purugganan, M. D.; Andersson, L.; Arroyo-Kalin, M.; Barton, L.; Climer Vigueira, C.; Denham, T.; Dobney, K.; Doust, A. N.; Gepts, P.; Gilbert, M. T. P.; Gremillion, K. J.; Lucas, L.; Lukens, L.; Marshall, F. B.; Olsen, K. M.; Pires, J.C.; Richerson, P. J.; Rubio De Casas, R.; Sanjur, O.I.; Thomas, M. G.; Fuller, D.Q. Current perspectives and the future of domestication studies. PNAS. 2014, 111 (17): 6139–6146. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6139L. PMC 4035915

. PMID 24757054. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323964111

. PMID 24757054. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323964111  .

.

- ^ Denham, T. P. Origins of Agriculture at Kuk Swamp in the Highlands of New Guinea. Science. 2003, 301 (5630): 189–193. PMID 12817084. S2CID 10644185. doi:10.1126/science.1085255.

- ^ Bocquet-Appel, Jean-Pierre. When the World's Population Took Off: The Springboard of the Neolithic Demographic Transition. Science. 2011-07-29, 333 (6042): 560–561. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..560B. PMID 21798934. S2CID 29655920. doi:10.1126/science.1208880.

- ^ Stephens, Lucas; Fuller, Dorian; Boivin, Nicole; Rick, Torben; Gauthier, Nicolas; Kay, Andrea; Marwick, Ben; Armstrong, Chelsey Geralda; Barton, C. Michael. Archaeological assessment reveals Earth's early transformation through land use. Science. 2019-08-30, 365 (6456): 897–902. Bibcode:2019Sci...365..897S. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31467217. S2CID 201674203. doi:10.1126/science.aax1192. hdl:10150/634688

.

.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Harmon, Katherine. Humans feasting on grains for at least 100,000 years. Scientific American. 2009-12-17 [2016-08-28]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-17).

- ^ Snir, Ainit; Nadel, Dani; Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Melamed, Yoel; Sternberg, Marcelo; Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Weiss, Ehud. The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long Before Neolithic Farming. PLOS ONE. 2015-07-22, 10 (7): e0131422. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1031422S. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4511808

. PMID 26200895. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422

. PMID 26200895. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ First evidence of farming in Mideast 23,000 years ago: Evidence of earliest small-scale agricultural cultivation. ScienceDaily. [2022-04-23]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-23) (英语).

- ^ Zong, Y.; When, Z.; Innes, J. B.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. Fire and flood management of coastal swamp enabled first rice paddy cultivation in east China. Nature. 2007, 449 (7161): 459–462. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..459Z. PMID 17898767. S2CID 4426729. doi:10.1038/nature06135.

- ^ Ensminger, M. E.; Parker, R. O. Sheep and Goat Science Fifth. Interstate Printers and Publishers. 1986. ISBN 978-0-8134-2464-4.

- ^ McTavish, E. J.; Decker, J. E.; Schnabel, R.D.; Taylor, J. F.; Hillis, D. M. New World cattle show ancestry from multiple independent domestication events. PNAS. 2013, 110 (15): E1398–1406. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E1398M. PMC 3625352

. PMID 23530234. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303367110

. PMID 23530234. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303367110  .

.

- ^ Larson, Greger; Dobney, Keith; Albarella, Umberto; Fang, Meiying; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth; Robins, Judith; Lowden, Stewart; Finlayson, Heather; Brand, Tina. Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Boar Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication. Science. 2005-03-11, 307 (5715): 1618–1621. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1618L. PMID 15761152. S2CID 39923483. doi:10.1126/science.1106927.

- ^ Larson, Greger; Albarella, Umberto; Dobney, Keith; Rowley-Conwy, Peter; Schibler, Jörg; Tresset, Anne; Vigne, Jean-Denis; Edwards, Ceiridwen J.; Schlumbaum, Angela. Ancient DNA, pig domestication, and the spread of the Neolithic into Europe. PNAS. 2007-09-25, 104 (39): 15276–15281. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415276L. PMC 1976408

. PMID 17855556. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703411104

. PMID 17855556. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703411104  .

.

- ^ Broudy, Eric. The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present. UPNE. 1979: 81 [2019-02-10]. ISBN 978-0-87451-649-4. (原始内容存档于2018-02-10).

- ^ Johannessen, S.; Hastorf, C. A. (eds.) Corn and Culture in the Prehistoric New World, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

- ^ Dance, Amber. The tale of the domesticated horse. Knowable Magazine. 2022-05-04 [2023-02-28]. doi:10.1146/knowable-050422-1

. (原始内容存档于2022-09-29).

. (原始内容存档于2022-09-29).

- ^ Hillman, G. C. (1996) "Late Pleistocene changes in wild plant-foods available to hunter-gatherers of the northern Fertile Crescent: Possible preludes to cereal cultivation". In D. R. Harris (ed.) The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, UCL Books, London, pp. 159–203. ISBN 9781857285383

- ^ Sato, Y. (2003) "Origin of rice cultivation in the Yangtze River basin". In Y. Yasuda (ed.) The Origins of Pottery and Agriculture, Roli Books, New Delhi, p. 196

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Gerritsen, R. Australia and the Origins of Agriculture. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Archaeopress. 2008: 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4073-0354-3. S2CID 129339276. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1896.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions. Science. 2003, 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523

. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469. doi:10.1126/science.1078208.

. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469. doi:10.1126/science.1078208.

- ^ Farming. British Museum. [2016-06-15]. (原始内容存档于2016-06-16).

- ^ Janick, Jules. Ancient Egyptian Agriculture and the Origins of Horticulture (PDF). Acta Hort.: 23–39. [2018-04-01]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-05-25).

- ^ Kees, Herman. Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Topography

. University of Chicago Press. 1961. ISBN 9780226429144.

. University of Chicago Press. 1961. ISBN 9780226429144.

- ^ Gupta, Anil K. Origin of agriculture and domestication of plants and animals linked to early Holocene climate amelioration (PDF). Current Science. 2004, 87 (1): 59 [2019-04-23]. JSTOR 24107979. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-01-20).

- ^ Baber, Zaheer (1996). The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India. State University of New York Press. 19. ISBN 0-7914-2919-9.

- ^ Harris, David R. and Gosden, C. (1996). The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia: Crops, Fields, Flocks And Herds. Routledge. p. 385. ISBN 1-85728-538-7.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (1996). Mehrgarh in Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Ed. Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Stein, Burton (1998). A History of India. Blackwell Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 0-631-20546-2.

- ^ Lal, R. Thematic evolution of ISTRO: transition in scientific issues and research focus from 1955 to 2000. Soil and Tillage Research. 2001, 61 (1–2): 3–12. doi:10.1016/S0167-1987(01)00184-2.

- ^ Needham, Vol. 6, Part 2, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Needham, Vol. 4, Part 2, pp. 89, 110, 184.

- ^ Needham, Vol. 4, Part 2, p. 110.

- ^ Greenberger, Robert (2006) The Technology of Ancient China, Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 11–12. ISBN 1404205586

- ^ Wang Zhongshu, trans. by K. C. Chang and Collaborators, Han Civilization (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982).

- ^ Glick, Thomas F. Medieval Science, Technology And Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Volume 11 of The Routledge Encyclopedias of the Middle Ages Series. Psychology Press. 2005: 270 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Molina, J.; Sikora, M.; Garud, N.; Flowers, J. M.; Rubinstein, S.; Reynolds, A.; Huang, P.; Jackson, S.; Schaal, B. A.; Bustamante, C. D.; Boyko, A. R.; Purugganan, M. D. Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011, 108 (20): 8351–8356. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8351M. PMC 3101000

. PMID 21536870. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104686108

. PMID 21536870. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104686108  .

.

- ^ Huang, Xuehui; Kurata, Nori; Wei, Xinghua; Wang, Zi-Xuan; Wang, Ahong; Zhao, Qiang; Zhao, Yan; Liu, Kunyan; et al. A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature. 2012, 490 (7421): 497–501. Bibcode:2012Natur.490..497H. PMC 7518720

. PMID 23034647. doi:10.1038/nature11532

. PMID 23034647. doi:10.1038/nature11532  .

.

- ^ Koester, Helmut (1995), History, Culture, and Religion of the Hellenistic Age, 2nd edition, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 76–77. ISBN 3-11-014693-2

- ^ White, K. D. (1970), Roman Farming. Cornell University Press.

- ^ 46.0 46.1 Murphy, Denis. Plants, Biotechnology and Agriculture. CABI. 2011: 153 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-1-84593-913-7. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Davis, Nicola. Origin of chocolate shifts 1,400 miles and 1,500 years. The Guardian. 2018-10-29 [2018-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-30).

- ^ Speller, Camilla F.; et al. Ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals complexity of indigenous North American turkey domestication. PNAS. 2010, 107 (7): 2807–2812. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.2807S. PMC 2840336

. PMID 20133614. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909724107

. PMID 20133614. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909724107  .

.

- ^ Mascarelli, Amanda. Mayans converted wetlands to farmland. Nature. 2010-11-05 [2013-05-17]. doi:10.1038/news.2010.587. (原始内容存档于2021-04-23).

- ^ Morgan, John. Invisible Artifacts: Uncovering Secrets of Ancient Maya Agriculture with Modern Soil Science. Soil Horizons. 2013-11-06, 53 (6): 3. doi:10.2136/sh2012-53-6-lf

.

.

- ^ Spooner, David M.; McLean, Karen; Ramsay, Gavin; Waugh, Robbie; Bryan, Glenn J. A single domestication for potato based on multilocus amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping. PNAS. 2005, 102 (41): 14694–14699. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214694S. PMC 1253605

. PMID 16203994. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507400102

. PMID 16203994. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507400102  .

.

- ^ Office of International Affairs. Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. nap.edu. 1989: 92 [2018-04-01]. ISBN 978-0-309-04264-2. doi:10.17226/1398. (原始内容存档于2012-12-02).

- ^ Francis, John Michael. Iberia and the Americas. ABC-CLIO. 2005 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-1-85109-426-4. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Broudy, Eric. The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present. UPNE. 1979: 81 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-0-87451-649-4. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Rischkowsky, Barbara; Pilling, Dafydd. The State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Food & Agriculture Organization. 2007: 10. ISBN 978-92-5-105762-9.

- ^ Heiser, Carl B. Jr. On possible sources of the tobacco of prehistoric Eastern North America. Current Anthropology. 1992, 33: 54–56. S2CID 144433864. doi:10.1086/204032.

- ^ Ford, Richard I. Prehistoric Food Production in North América. University of Michigan, Museum of Anthropology, Publications Department. 1985: 75 [2019-04-23]. ISBN 978-0-915703-01-2. (原始内容存档于2020-03-09).

- ^ Adair, Mary J. (1988) Prehistoric Agriculture in the Central Plains. Publications in Anthropology 16. University of Kansas, Lawrence.

- ^ Smith, Andrew. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. OUP USA. 2013: 1 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-0-19-973496-2. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Hardigan, Michael A. P0653: Domestication History of Strawberry: Population Bottlenecks and Restructuring of Genetic Diversity through Time. Pland & Animal Genome Conference XXVI 13–17 January 2018 San Diego, California. [2018-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2018-03-01).

- ^ Sugihara, Neil G.; Van Wagtendonk, Jan W.; Shaffer, Kevin E.; Fites-Kaufman, Joann; Thode, Andrea E. (编). 17. Fire in California's Ecosystems

. University of California Press. 2006: 417. ISBN 978-0-520-24605-8.

. University of California Press. 2006: 417. ISBN 978-0-520-24605-8.

- ^ Blackburn, Thomas C.; Anderson, Kat (编). Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians. Ballena Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-87919-126-9.

- ^ Cunningham, Laura. State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California. Heyday. 2010: 135, 173–202 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-1-59714-136-9. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Anderson, M. Kat. Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge And the Management of California's Natural Resources

. University of California Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-520-24851-9.

. University of California Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-520-24851-9.

- ^ Wilson, Gilbert. Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation. Dodo Press. 1917: 25 and passim. ISBN 978-1-4099-4233-7. (原始内容存档于2016-03-14).

- ^ Landon, Amanda J. The "How" of the Three Sisters: The Origins of Agriculture in Mesoamerica and the Human Niche. Nebraska Anthropologist. 2008: 110–124 [2018-04-01]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-21).

- ^ Jones, R. Fire-stick Farming. Fire Ecology. 2012, 8 (3): 3–8. doi:10.1007/BF03400623

.

.

- ^ MLA Rowley-Conwy, Peter, and Robert Layton. "Foraging and farming as niche construction: stable and unstable adaptations." Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences vol. 366,1566 (2011): 849–62. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0307

- ^ Williams, Elizabeth. Complex Hunter-Gatherers: A Late Holocene Example from Temperate Australia. Archaeopress Archaeology. 1988, 423.

- ^ Gammage, Bill. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. October 2011: 281–304 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ National Geographic. Food Journeys of a Lifetime. National Geographic Society. 2015: 126 [2023-02-28]. ISBN 978-1-4262-1609-1. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Watson, Andrew M. The Arab Agricultural Revolution and Its Diffusion, 700–1100. The Journal of Economic History. 1974, 34 (1): 8–35. S2CID 154359726. doi:10.1017/s0022050700079602.

- ^ Crosby, Alfred. The Columbian Exchange. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. [2013-05-11]. (原始内容存档于2013-07-03).

- ^ Janick, Jules. Agricultural Scientific Revolution: Mechanical (PDF). Purdue University. [2013-05-24]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-05-25).

- ^ Reid, John F. The Impact of Mechanization on Agriculture. The Bridge on Agriculture and Information Technology. 2011, 41 (3). (原始内容存档于2013-11-05).

- ^ 76.0 76.1 Philpott, Tom. A Brief History of Our Deadly Addiction to Nitrogen Fertilizer. Mother Jones. 2013-04-19 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-05).

- ^ Ten worst famines of the 20th century. Sydney Morning Herald. 2011-08-15. (原始内容存档于2014-07-03).

- ^ Blench, Roger. Pastoralists in the new millennium (PDF). FAO. 2001: 11–12. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-02-01).

- ^ Shifting cultivation. Survival International. [2016-08-28]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-29).

- ^ Waters, Tony. The Persistence of Subsistence Agriculture: life beneath the level of the marketplace. Lexington Books. 2007.

- ^ Chinese project offers a brighter farming future. Editorial. Nature. 2018-03-07, 555 (7695): 141. Bibcode:2018Natur.555R.141.. PMID 29517037. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-02742-3

.

.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica's definition of Intensive Agriculture. (原始内容存档于2006-07-05).

- ^ BBC School fact sheet on intensive farming. (原始内容存档于2007-05-03).

- ^ Lowder, Sarah K.; Sánchez, Marco V.; Bertini, Raffaele. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? 142: 105455. 2021-06-01 [2023-02-28]. ISSN 0305-750X. S2CID 233553897. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105455. (原始内容存档于2023-02-16) (英语).

- ^ Wheat Stem Rust – UG99 (Race TTKSK). FAO. [2014-01-06]. (原始内容存档于2014-01-07).

- ^ Sample, Ian (31 August 2007). "Global food crisis looms as climate change and population growth strip fertile land" 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2016-04-29., The Guardian (London).

- ^ Africa may be able to feed only 25% of its population by 2025. Mongabay. 2006-12-14 [2016-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-27).

- ^ Scheierling, Susanne M. Overcoming agricultural pollution of water: the challenge of integrating agricultural and environmental policies in the European Union, Volume 1. The World Bank. 1995 [2013-04-15]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-05).

- ^ CAP Reform. European Commission. 2003 [2013-04-15]. (原始内容存档于2010-10-17).

- ^ Poincelot, Raymond P. Organic Farming. Toward a More Sustainable Agriculture. 1986: 14–32. ISBN 978-1-4684-1508-7. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-1506-3_2.

- ^ The cutting-edge technology that will change farming. Agweek. 2018-11-09 [2018-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-17).

- ^ Charles, Dan. Hydroponic Veggies Are Taking Over Organic, And A Move To Ban Them Fails. NPR. 2017-11-03 [2018-11-24]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-24).

- ^ Knapp, Samuel; van der Heijden, Marcel G. A. A global meta-analysis of yield stability in organic and conservation agriculture. Nature Communications. 2018-09-07, 9 (1): 3632. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6128901

. PMID 30194344. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05956-1 (英语).

. PMID 30194344. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05956-1 (英语).

- ^ GM Science Review First Report 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2013-10-16., Prepared by the UK GM Science Review panel (July 2003). Chairman David King, p. 9

- ^ UNCTADstat – Table view. [2017-11-26]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-20).

- ^ Agricultural Productivity in the United States. USDA Economic Research Service. 2012-07-05 [2013-04-22]. (原始内容存档于2013-02-01).

- ^ 97.0 97.1 97.2 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2022 [2023-03-05]. ISBN 978-92-5-136499-4. doi:10.4060/cc0639en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ In Brief to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2022 [2023-03-05]. ISBN 978-92-5-136502-1. doi:10.4060/cc0640en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Food prices: smallholder farmers can be part of the solution. International Fund for Agricultural Development. [2013-04-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-05).

- ^ World Bank. 2021. Employment in agriculture (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate). The World Bank. Washington, DC. 2021 [2021-05-12]. (原始内容存档于2019-10-07).

- ^ Michaels, Guy; Rauch, Ferdinand; Redding, Stephen J. Urbanization and Structural Transformation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2012, 127 (2): 535–586 [2023-03-01]. ISSN 0033-5533. JSTOR 23251993. doi:10.1093/qje/qjs003. (原始内容存档于2023-02-03).

- ^ Gollin, Douglas; Parente, Stephen; Rogerson, Richard. The Role of Agriculture in Development. The American Economic Review. 2002, 92 (2): 160–164 [2023-03-01]. ISSN 0002-8282. JSTOR 3083394. doi:10.1257/000282802320189177. (原始内容存档于2023-02-03).

- ^ Lewis, W. Arthur. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. The Manchester School. 1954, 22 (2): 139–191 [2023-03-01]. ISSN 1463-6786. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9957.1954.tb00021.x. (原始内容存档于2023-02-03) (英语).

- ^ FAOSTAT: Employment Indicators: Agriculture. FAO. Rome. 2022 [2022-02-06]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-12).

- ^ Allen, Robert C. Economic structure and agricultural productivity in Europe, 1300–1800 (PDF). European Review of Economic History: 1–25. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2014-10-27).

- ^ Labor Force – By Occupation. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. [2013-05-04]. (原始内容存档于2014-05-22).

- ^ Safety and health in agriculture. International Labour Organization. 2011-03-21 [2018-04-01]. (原始内容存档于2018-03-18).

- ^ Services sector overtakes farming as world's biggest employer: ILO. The Financial Express. Associated Press. 2007-01-26 [2013-04-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-13).

- ^ In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2018. Migration, agriculture and rural development. Rome: FAO. 2018 [2023-03-05]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-03).

- ^ Caruso, F. & Corrado, A. Migrazioni e lavoro agricolo: un confronto tra Italia e Spagna in tempi di crisi. M. Colucci & S. Gallo (编). Tempo di cambiare. Rapporto 2015 sulle migrazioni interne in Italia. Rome: Donizelli. 2015: 58–77.

- ^ Kasimis, Charalambos. Migrants in the Rural Economies of Greece and Southern Europe. migrationpolicy.org. 2005-10-01 [2023-02-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-06) (英语).

- ^ Nori, M. The shades of green: Migrants' contribution to EU agriculture. Context, trends, opportunities, challenges. Florence: Migration Policy Centre. 2017.

- ^ Fonseca, Maria Lucinda. New waves of immigration to small towns and rural areas in Portugal: Immigration to Rural Portugal. Population, Space and Place. November 2008, 14 (6): 525–535 [2023-03-05]. doi:10.1002/psp.514. (原始内容存档于2023-02-06) (英语).

- ^ Preibisch, Kerry. Pick-Your-Own Labor: Migrant Workers and Flexibility in Canadian Agriculture. The International Migration Review. 2010, 44 (2): 404–441 [2023-03-05]. ISSN 0197-9183. JSTOR 25740855. S2CID 145604068. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00811.x. (原始内容存档于2023-02-06).

- ^ Agriculture: How immigration plays a critical role. New American Economy. [2023-02-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-04-06) (美国英语).

- ^ 116.0 116.1 116.2 116.3 The State of Food and Agriculture 2017. Leveraging food systems for inclusive rural transformation. Rome: FAO. 2017 [2023-03-05]. ISBN 978-92-5-109873-8. (原始内容存档于2023-03-14).

- ^ NIOSH Workplace Safety & Health Topic: Agricultural Injuries. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-28).

- ^ NIOSH Pesticide Poisoning Monitoring Program Protects Farmworkers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011 [2013-04-15]. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2012108

. (原始内容存档于2013-04-02).

. (原始内容存档于2013-04-02).

- ^ 119.0 119.1 NIOSH Workplace Safety & Health Topic: Agriculture. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-09).

- ^ 120.0 120.1 Weichelt, Bryan; Gorucu, Serap. Supplemental surveillance: a review of 2015 and 2016 agricultural injury data from news reports on AgInjuryNews.org. Injury Prevention. 2018-02-17, 25 (3): injuryprev–2017–042671 [2018-04-18]. PMID 29386372. S2CID 3371442. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042671. (原始内容存档于2018-04-27).

- ^ The PLOS ONE staff. Correction: Towards a deeper understanding of parenting on farms: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE. 2018-09-06, 13 (9): e0203842. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1303842.. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6126865

. PMID 30188948. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203842

. PMID 30188948. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203842  .

.

- ^ 122.0 122.1 122.2 Safety and health in agriculture. 国际劳工组织. 2011-03-21 [2018-04-01]. (原始内容存档于2018-03-18).

- ^ CDC – NIOSH – NORA Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing Sector Council. NIOSH. 2018-03-21 [2018-04-07]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-18).

- ^ CDC – NIOSH Program Portfolio : Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing : Program Description. NIOSH. 2018-02-28 [2018-04-07]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-08).

- ^ Protecting health and safety of workers in agriculture, livestock farming, horticulture and forestry. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. 2017-08-17 [2018-04-10]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-29).

- ^ Heiberger, Scott. The future of agricultural safety and health: North American Agricultural Safety Summit, February 2018, Scottsdale, Arizona. Journal of Agromedicine. 2018-07-03, 23 (3): 302–304. ISSN 1059-924X. PMID 30047853. S2CID 51721534. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1485089.

- ^ UNCTADstat – Table view. [2017-11-26]. (原始内容存档于2017-10-20).

- ^ Analysis of farming systems. Food and Agriculture Organization. [2013-05-22]. (原始内容存档于2013-08-06).

- ^ 129.0 129.1 "Agricultural Production Systems". pp. 283–317 in Acquaah.

- ^ 130.0 130.1 130.2 130.3 130.4 130.5 130.6 "Farming Systems: Development, Productivity, and Sustainability", pp. 25–57 in Chrispeels

- ^ 131.0 131.1 131.2 131.3 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAOSTAT). [2013-02-02]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-18).

- ^ Profiles of 15 of the world's major plant and animal fibres. FAO. 2009 [2018-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-03).

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge University Press. 1999: 1–2 [2023-03-07]. ISBN 978-0-521-63495-3. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Falvey, John Lindsay. Introduction to Working Animals. Melbourne, Australia: MPW Australia. 1985. ISBN 978-1-86252-992-2.

- ^ 135.0 135.1 Sere, C.; Steinfeld, H.; Groeneweld, J. Description of Systems in World Livestock Systems – Current status issues and trends. U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. 1995 [2013-09-08]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-26).

- ^ 136.0 136.1 Thornton, Philip K. Livestock production: recent trends, future prospects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2010-09-27, 365 (1554): 2853–2867. PMC 2935116

. PMID 20713389. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0134

. PMID 20713389. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0134  .

.

- ^ Stier, Ken. Fish Farming's Growing Dangers. Time. 2007-09-19. (原始内容存档于2013-09-07).

- ^ Ajmone-Marsan, P. A global view of livestock biodiversity and conservation – Globaldiv. Animal Genetics. May 2010, 41 (supplement S1): 1–5. PMID 20500752. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02036.x. (原始内容存档于2017-08-03).

- ^ Growth Promoting Hormones Pose Health Risk to Consumers, Confirms EU Scientific Committee (PDF). European Union. 2002-04-23 [2013-04-06]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-05-02).

- ^ 140.0 140.1 Brady, N. C.; Weil, R. R. (2002). "Practical Nutrient Management" pp. 472–515 in Elements of the Nature and Properties of Soils. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. ISBN 978-0135051955

- ^ "Land Preparation and Farm Energy", pp. 318–338 in Acquaah

- ^ "Pesticide Use in U.S. Crop Production", pp. 240–282 in Acquaah

- ^ "Soil and Land", pp. 165–210 in Acquaah

- ^ "Nutrition from the Soil", pp. 187–218 in Chrispeels

- ^ "Plants and Soil Water", pp. 211–239 in Acquaah

- ^ 146.0 146.1 146.2 146.3 146.4 146.5 146.6 146.7 146.8 The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Leveraging agricultural automation for transforming agrifood systems. Rome: FAO. 2022 [2023-03-09]. ISBN 978-92-5-136043-9. doi:10.4060/cb9479en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Pimentel, D.; Berger, D.; Filberto, D.; Newton, M. Water Resources: Agricultural and Environmental Issues. BioScience. 2004, 54 (10): 909–918. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0909:WRAAEI]2.0.CO;2

.

.

- ^ The State of Food and Agriculture 2020. Overcoming water challenges in agriculture. Rome: FAO. 2020 [2023-03-09]. ISBN 978-92-5-133441-6. S2CID 241788672. doi:10.4060/cb1447en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ International Food Policy Research Institute. Food Security in a World of Growing Natural Resource Scarcity. CropLife International. 2014 [2013-07-01]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-05).

- ^ Tacconi, L. Redefining payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics. 2012, 73 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.09.028.

- ^ Gan, H.; Lee, W. S. Development of a Navigation System for a Smart Farm. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 6th IFAC Conference on Bio-Robotics BIOROBOTICS 2018. 2018-01-01, 51 (17): 1–4. ISSN 2405-8963. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2018.08.051 (英语).

- ^ Lowenberg-DeBoer, James; Huang, Iona Yuelu; Grigoriadis, Vasileios; Blackmore, Simon. Economics of robots and automation in field crop production. Precision Agriculture. 2020-04-01, 21 (2): 278–299 [2023-03-09]. ISSN 1573-1618. doi:10.1007/s11119-019-09667-5. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13) (英语).

- ^ 153.0 153.1 153.2 153.3 In Brief to The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Leveraging automation in agriculture for transforming agrifood systems. Rome: FAO. 2022 [2023-03-09]. ISBN 978-92-5-137005-6. doi:10.4060/cc2459en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ 154.0 154.1 154.2 Santos Valle, S. & Kienzle, J. Agriculture 4.0 – Agricultural robotics and automated equipment for sustainable crop production. FAO. 2020 [2023-03-09]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-10).

- ^ Milking Robots Market Size, Share, Trends, Opportunities & Forecast. Verified Market Research. [2023-02-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-01) (美国英语).

- ^ Rodenburg, Jack. Robotic milking: Technology, farm design, and effects on work flow. Journal of Dairy Science. 2017, 100 (9): 7729–7738 [2023-03-09]. ISSN 0022-0302. PMID 28711263. doi:10.3168/jds.2016-11715. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. Economics of adoption for digital automated technologies in agriculture. Background paper for The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Rome: FAO. 2022 [2023-03-09]. ISBN 978-92-5-137080-3. doi:10.4060/cc2624en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ 158.0 158.1 158.2 Enabling inclusive agricultural automation. Rome: FAO. 2022 [2023-03-09]. ISBN 978-92-5-137099-5. doi:10.4060/cc2688en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Milius, Susan. Worries grow that climate change will quietly steal nutrients from major food crops. Science News. 2017-12-13 [2018-01-21]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-23).

- ^ Hoffmann, U., Section B: Agriculture – a key driver and a major victim of global warming, in: Lead Article, in: Chapter 1, in Hoffmann, U. (编). Trade and Environment Review 2013: Wake up before it is too late: Make agriculture truly sustainable now for food security in a changing climate. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2013: 3, 5. (原始内容存档于2014-11-28).

- ^ 161.0 161.1 Porter, J. R., et al.., Executive summary, in: Chapter 7: Food security and food production systems 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2014-11-05.(archived ), in IPCC AR5 WG2 A. Field, C. B.; et al , 编. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II (WG2) to the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press. 2014: 488–489 [2018-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-16).

- ^ Paragraph 4, in: Summary and Recommendations, in: HLPE. Food security and climate change. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. June 2012: 12. (原始内容存档于2014-12-12).

- ^ History of Plant Breeding. Colorado State University. 2004-01-29 [2013-05-11]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-21).

- ^ Stadler, L. J.; Sprague, G.F. Genetic Effects of Ultra-Violet Radiation in Maize: I. Unfiltered Radiation (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1936-10-15, 22 (10): 572–578 [2007-10-11]. Bibcode:1936PNAS...22..572S. PMC 1076819

. PMID 16588111. doi:10.1073/pnas.22.10.572

. PMID 16588111. doi:10.1073/pnas.22.10.572  . (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2007-10-24).

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2007-10-24).

- ^ Berg, Paul; Singer, Maxine. George Beadle: An Uncommon Farmer. The Emergence of Genetics in the 20th century

. Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory Press. 2003-08-15. ISBN 978-0-87969-688-7.

. Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory Press. 2003-08-15. ISBN 978-0-87969-688-7.

- ^ Ruttan, Vernon W. Biotechnology and Agriculture: A Skeptical Perspective (PDF). AgBioForum. December 1999, 2 (1): 54–60. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-05-21).

- ^ Cassman, K. Ecological intensification of cereal production systems: The Challenge of increasing crop yield potential and precision agriculture. Proceedings of a National Academy of Sciences Colloquium, Irvine, California. 1998-12-05 [2007-10-11]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-24).

- ^ Conversion note: 1 bushel of wheat=60 pounds (lb) ≈ 27.215 kg. 1 bushel of maize=56 pounds ≈ 25.401 kg

- ^ 20 Questions on Genetically Modified Foods. World Health Organization. [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-27).

- ^ Whiteside, Stephanie. Peru bans genetically modified foods as US lags. Current TV. 2012-11-28 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-24).

- ^ Shiva, Vandana. Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability, and Peace. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. 2005.

- ^ Kathrine Hauge Madsen; Jens Carl Streibig. Benefits and risks of the use of herbicide-resistant crops. Weed Management for Developing Countries. FAO. [2013-05-04]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-04).

- ^ Farmers Guide to GMOs (PDF). Rural Advancement Foundation International. 2013-01-11 [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-05-01).

- ^ Hindo, Brian. Report Raises Alarm over 'Super-weeds'. Bloomberg BusinessWeek. 2008-02-13. (原始内容存档于2016-12-26).

- ^ Ozturk; et al. Glyphosate inhibition of ferric reductase activity in iron deficient sunflower roots. New Phytologist. 2008, 177 (4): 899–906. PMID 18179601. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02340.x

. (原始内容存档于2017-01-13).

. (原始内容存档于2017-01-13).

- ^ Insect-resistant Crops Through Genetic Engineering. University of Illinois. [2013-05-04]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-21).

- ^ Kimbrell, A. Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture. Washington: Island Press. 2002.

- ^ Making Peace with Nature: A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies. United Nations Environment Programme. 2021 [2021-06-09]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-23).

- ^ International Resource Panel. Priority products and materials: assessing the environmental impacts of consumption and production. United Nations Environment Programme. 2010 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2012-12-24).

- ^ Frouz, Jan; Frouzová, Jaroslava. Applied Ecology. 2022 [2021-12-19]. ISBN 978-3-030-83224-7. S2CID 245009867. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-83225-4. (原始内容存档于2022-01-29).

- ^ 181.0 181.1 Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication. UNEP. 2011 [2021-06-09]. (原始内容存档于2020-05-10).

- ^ 182.0 182.1 Pretty, J.; et al. An assessment of the total external costs of UK agriculture. Agricultural Systems. 2000, 65 (2): 113–136. doi:10.1016/S0308-521X(00)00031-7

. (原始内容存档于2017-01-13).

. (原始内容存档于2017-01-13).

- ^ 183.0 183.1 Tegtmeier, E. M.; Duffy, M. External Costs of Agricultural Production in the United States (PDF). The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Agriculture. 2005. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2009-02-05).

- ^ Richards, A. J. Does Low Biodiversity Resulting from Modern Agricultural Practice Affect Crop Pollination and Yield?. Annals of Botany. 2001, 88 (2): 165–172. doi:10.1006/anbo.2001.1463

.

.

- ^ The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2019: 12 [2021-05-04]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-29).

- ^ French firm breeds plants that resist climate change. European Investment Bank. [2023-01-25]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-02) (英语).

- ^ New virulent disease threatens wheat crops in Europe and North Africa - researchers. Reuters. 2017-02-03 [2023-01-25]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-25) (英语).

- ^ Livestock a major threat to environment. UN Food and Agriculture Organization. 2006-11-29 [2013-04-24]. (原始内容存档于2008-03-28).

- ^ Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock's Long Shadow – Environmental issues and options (PDF). Rome: U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2006 [2008-12-05]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-06-25).

- ^ Vitousek, P. M.; Mooney, H. A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J. M. Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems. Science. 1997, 277 (5325): 494–499. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.6529

. doi:10.1126/science.277.5325.494.

. doi:10.1126/science.277.5325.494.

- ^ Bai, Z.G.; Dent, D.L.; Olsson, L. & Schaepman, M.E. Global assessment of land degradation and improvement: 1. identification by remote sensing (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization/ISRIC. November 2008 [2013-05-24]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-12-13).

- ^ Carpenter, S. R.; Caraco, N. F.; Correll, D. L.; Howarth, R. W.; Sharpley, A. N.; Smith, V. H. Nonpoint Pollution of Surface Waters with Phosphorus and Nitrogen. Ecological Applications. 1998, 8 (3): 559–568. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0559:NPOSWW]2.0.CO;2. hdl:1808/16724

.

.

- ^ Hautier, Y.; Niklaus, P. A.; Hector, A. Competition for Light Causes Plant Biodiversity Loss After Eutrophication (PDF). Science (Submitted manuscript). 2009, 324 (5927): 636–638 [2018-11-03]. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..636H. PMID 19407202. S2CID 21091204. doi:10.1126/science.1169640. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-11-02).

- ^ Molden, D. (编). Findings of the Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture (PDF). Annual Report 2006/2007. International Water Management Institute. [2014-01-06]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2014-01-07).

- ^ European Investment Bank. On Water. European Investment Bank (European Investment Bank). 2019 [2020-12-07]. ISBN 9789286143199. doi:10.2867/509830. (原始内容存档于2020-11-29) (英语).

- ^ Li, Sophia. Stressed Aquifers Around the Globe. The New York Times. 2012-08-13 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-04-02).

- ^ Water Use in Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization. November 2005 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-15).

- ^ Water Management: Towards 2030. Food and Agriculture Organization. March 2003 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-10).

- ^ Pimentel, D.; Culliney, T. W.; Bashore, T. Public health risks associated with pesticides and natural toxins in foods. Radcliffe's IPM World Textbook. 1996 [2013-05-07]. (原始内容存档于1999-02-18).

- ^ Our planet, our health: Report of the WHO commission on health and environment. Geneva: World Health Organization (1992).

- ^ 201.0 201.1 "Strategies for Pest Control", pp. 355–383 in Chrispeels

- ^ Avery, D.T. Saving the Planet with Pesticides and Plastic: The Environmental Triumph of High-Yield Farming

. Indianapolis: Hudson Institute. 2000. ISBN 9781558130692.

. Indianapolis: Hudson Institute. 2000. ISBN 9781558130692.

- ^ Center for Global Food Issues. Center for Global Food Issues. [2016-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2016-02-21).

- ^ Lappe, F. M.; Collins, J.; Rosset, P. (1998). "Myth 4: Food vs. Our Environment" 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-03-04., pp. 42–57 in World Hunger, Twelve Myths, Grove Press, New York. ISBN 9780802135919

- ^ Cook, Samantha M.; Khan, Zeyaur R.; Pickett, John A. The use of push-pull strategies in integrated pest management. Annual Review of Entomology. 2007, 52: 375–400. PMID 16968206. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091407.

- ^ Section 4.2: Agriculture's current contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, in: HLPE. Food security and climate change. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. June 2012: 67–69. (原始内容存档于2014-12-12).

- ^ Nabuurs, G-J.; Mrabet, R.; Abu Hatab, A.; Bustamante, M.; et al. Chapter 7: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. : 750 [2023-03-24]. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.009 (不活跃 13 February 2023). (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-03-07)..

- ^ FAO. Emissions due to agriculture. Global, regional and country trends 2000–2018. (PDF) (报告). FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series 18. Rome: 2. 2020 [2023-03-24]. ISSN 2709-0078. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-12-22).

- ^ How livestock farming affects the environment. www.downtoearth.org.in. [2022-02-10]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-30) (英语).

- ^ Xu, Xiaoming; Sharma, Prateek; Shu, Shijie; Lin, Tzu-Shun; Ciais, Philippe; Tubiello, Francesco N.; Smith, Pete; Campbell, Nelson; Jain, Atul K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nature Food. 2021, 2 (9): 724–732 [2023-03-24]. ISSN 2662-1355. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00358-x. (原始内容存档于2023-04-03) (英语).

- ^ Boelee, E. (编). Ecosystems for water and food security. IWMI/UNEP. 2011 [2013-05-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-23).

- ^ Molden, D. Opinion: The Water Deficit (PDF). The Scientist. [2011-08-23]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-01-13).

- ^ Safefood Consulting, Inc. Benefits of Crop Protection Technologies on Canadian Food Production, Nutrition, Economy and the Environment. CropLife International. 2005 [2013-05-24]. (原始内容存档于2013-07-06).

- ^ Trewavas, Anthony. A critical assessment of organic farming-and-food assertions with particular respect to the UK and the potential environmental benefits of no-till agriculture. Crop Protection. 2004, 23 (9): 757–781. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2004.01.009.

- ^ Griscom, Bronson W.; Adams, Justin; Ellis, Peter W.; Houghton, Richard A.; Lomax, Guy; Miteva, Daniela A.; Schlesinger, William H.; Shoch, David; Siikamäki, Juha V.; Smith, Pete; Woodbury, Peter. Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017, 114 (44): 11645–11650. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11411645G. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5676916

. PMID 29078344. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710465114

. PMID 29078344. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710465114  .

.

- ^ National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019: 117, 125, 135. ISBN 978-0-309-48452-7. PMID 31120708. S2CID 134196575. doi:10.17226/25259.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019: 97 [2020-02-21]. ISBN 978-0-309-48452-7. PMID 31120708. S2CID 134196575. doi:10.17226/25259. (原始内容存档于2021-11-22).

- ^ Ecological Modelling. (原始内容存档于2018-01-23).

- ^ World oil supplies are set to run out faster than expected, warn scientists. The Independent. 2007-06-14 [2016-07-14]. (原始内容存档于2010-10-21).

- ^ Herdt, Robert W. The Future of the Green Revolution: Implications for International Grain Markets (PDF). The Rockefeller Foundation: 2. 1997-05-30 [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-10-19).

- ^ 221.0 221.1 221.2 Schnepf, Randy. Energy use in Agriculture: Background and Issues (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service. 2004-11-19 [2013-09-26]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-09-27).

- ^ Woods, Jeremy; Williams, Adrian; Hughes, John K.; Black, Mairi; Murphy, Richard. Energy and the food system. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. August 2010, 365 (1554): 2991–3006. PMC 2935130

. PMID 20713398. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0172

. PMID 20713398. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0172  .

.

- ^ Canning, Patrick; Charles, Ainsley; Huang, Sonya; Polenske, Karen R.; Waters, Arnold. Energy Use in the U.S. Food System. USDA Economic Research Service Report No. ERR-94. United States Department of Agriculture. 2010. (原始内容存档于2010-09-18).

- ^ Heller, Martin; Keoleian, Gregory. Life Cycle-Based Sustainability Indicators for Assessment of the U.S. Food System (PDF). University of Michigan Center for Sustainable Food Systems. 2000 [2016-03-17]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-14).

- ^ 225.0 225.1 225.2 UN Environment. Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics. UNEP – UN Environment Programme. 2021-10-21 [2022-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-21) (英语).

- ^ Meat Atlas. Heinrich Boell Foundation, Friends of the Earth Europe. 2014 [2018-04-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-22).

- ^ Hogan, Lindsay; Morris, Paul. Agricultural and food policy choices in Australia (PDF). Sustainable Agriculture and Food Policy in the 21st Century: Challenges and Solutions. October 2010: 13 [2013-04-22]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-12-15).

- ^ Agriculture: Not Just Farming. European Union. 2016-06-16 [2018-05-08]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-23).

- ^ 229.0 229.1 A multi-billion-dollar opportunity – Repurposing agricultural support to transform food systems. FAO, UNDP, and UNEP. 2021 [2023-03-24]. ISBN 978-92-5-134917-5. doi:10.4060/cb6562en. (原始内容存档于2023-04-13).

- ^ Ikerd, John. Corporatization of Agricultural Policy. Small Farm Today Magazine. 2010. (原始内容存档于2016-08-07).

- ^ Jowit, Juliette. Corporate Lobbying Is Blocking Food Reforms, Senior UN Official Warns: Farming Summit Told of Delaying Tactics by Large Agribusiness and Food Producers on Decisions that Would Improve Human Health and the Environment. The Guardian. 2010-09-22 [2018-05-08]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-05).

- ^ Agricultural Economics. University of Idaho. [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2013-04-01).

- ^ Runge, C. Ford. Agricultural Economics: A Brief Intellectual History (PDF). Center for International Food and Agriculture Policy: 4. June 2006 [2013-09-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-10-21).

- ^ Conrad, David E. Tenant Farming and Sharecropping. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. [2013-09-16]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-27).

- ^ Stokstad, Marilyn. Medieval Castles. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2005: 43 [2016-03-17]. ISBN 978-0-313-32525-0. (原始内容存档于2022-05-16).

- ^ Sexton, R. J. Industrialization and Consolidation in the US Food Sector: Implications for Competition and Welfare. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2000, 82 (5): 1087–1104. doi:10.1111/0002-9092.00106.

- ^ 237.0 237.1 Lloyd, Peter J.; Croser, Johanna L.; Anderson, Kym. How Do Agricultural Policy Restrictions to Global Trade and Welfare Differ across Commodities? (PDF). Policy Research Working Paper #4864. The World Bank: 2–3. March 2009 [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-06-05).

- ^ Anderson, Kym; Valenzuela, Ernesto. Do Global Trade Distortions Still Harm Developing Country Farmers? (PDF). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3901. World Bank: 1–2. April 2006 [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-06-05).

- ^ Kinnock, Glenys. America's $24bn subsidy damages developing world cotton farmers. The Guardian. 2011-05-24 [2013-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-06).

- ^ Agriculture's Bounty (PDF). May 2013 [2013-08-19]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-08-26).

- ^ Bosso, Thelma. Agricultural Science. Callisto Reference. 2015. ISBN 978-1-63239-058-5.

- ^ Boucher, Jude. Agricultural Science and Management. Callisto Reference. 2018. ISBN 978-1-63239-965-6.

- ^ 陈仁炫. 土壤強心針 - 科學月刊Science Monthly. 科学月刊. [2023-04-12]. (原始内容存档于2021-09-26) (中文(台湾)).

- ^ John Armstrong, Jesse Buel. A Treatise on Agriculture, The Present Condition of the Art Abroad and at Home, and the Theory and Practice of Husbandry. To which is Added, a Dissertation on the Kitchen and Garden. 1840. p. 45.

- ^ The Long Term Experiments. Rothamsted Research. [2018-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2018-03-27).

- ^ Silvertown, Jonathan; Poulton, Paul; Johnston, Edward; Edwards, Grant; Heard, Matthew; Biss, Pamela M. The Park Grass Experiment 1856–2006: its contribution to ecology. Journal of Ecology. 2006, 94 (4): 801–814. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01145.x

.

.

- ^ Coulson, J. R.; Vail, P. V.; Dix M. E.; Nordlund, D. A.; Kauffman, W. C.; Eds. 2000. 110 years of biological control research and development in the United States Department of Agriculture: 1883–1993. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. pages=3–11

- ^ History and Development of Biological Control (notes) (PDF). University of California Berkeley. [2017-04-10]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-11-24).

- ^ Reardon, Richard C. Biological Control of The Gypsy Moth: An Overview. Southern Appalachian Biological Control Initiative Workshop. [2017-04-10]. (原始内容存档于2016-09-05).

来源

- Acquaah, George. Principles of Crop Production: Theory, Techniques, and Technology. Prentice Hall. 2002. ISBN 978-0-13-022133-9.

- Chrispeels, Maarten J.; Sadava, David E. Plants, Genes, and Agriculture. Boston, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett. 1994. ISBN 978-0-86720-871-9.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China. Taipei: Caves Books. 1986.

![]() 本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。 在CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO下释出(许可证声明): 《Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics》, 联合国环境署. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。 在CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO下释出(许可证声明): 《Drowning in Plastics – Marine Litter and Plastic Waste Vital Graphics》, 联合国环境署. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

![]() 本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

![]() 本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable》, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable》, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

![]() 本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2018. Migration, agriculture and rural development》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2018. Migration, agriculture and rural development》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

![]() 本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief to The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Leveraging automation in agriculture for transforming agrifood systems》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《In Brief to The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Leveraging automation in agriculture for transforming agrifood systems》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

![]() 本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《Enabling inclusive agricultural automation》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

本条目包含了自由内容作品内的文本。(许可证声明): 《Enabling inclusive agricultural automation》, FAO, FAO. 欲了解如何向维基百科条目内添加开放许可证文本,请见这里;欲知如何重用本站文字,请见使用条款。

外部链接

- Food and Agriculture Organization (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- United States Department of Agriculture (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- 世界银行关于农业 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)的资料

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.