超级写实主义

超级写实主义(Hyperrealism,又称高度写实主义),是绘画和雕塑的一个流派,其风格类似高分辨率的照片。超级写实主义可以看作是照相写实主义(Photorealism)的发展。自2000年代早期以来,该术语在美国和欧洲作为一个独立的艺术运动和艺术风格发展起来。[1]

历史

[编辑]

法语术语“Hyperréalisme”由Isy Brachot创建于1973年。它是当年在他位于比利时布鲁塞尔的画廊的一个主要的展览的标题。该展览主要是由美国照相写实主义画家组成,包括拉尔夫·戈因斯(Ralph Goings)、查克·克洛斯(Chuck Close)、唐埃迪(Don Eddy)、罗伯特·贝克特尔(Robert Bechtle)和理查德·麦克莱恩(Richard McLean)。它还包括一些有影响力的欧洲艺术家。自此以来,“Hyperealisme”被欧洲艺术家和经销商用于形容受照相写实主义画家影响的画家。

21世纪初,超级写实主义在照相写实主义的美学基础上成立。美国照相写实主义画家丹尼斯·彼得森(Denis Peterson)的开拓性超级写实主义作为被普遍认为是照相写实主义的分支运动,第一次使用术语“Hyperrealism”来形容新的运动和相关的艺术家派别。[2][3][4]格雷厄姆·汤普森(Graham Thompson)写道,“1960年代末期和1970年代初期,照相写实主义作品获得成功,一种表现摄影的绘画方式加入到艺术世界。它也被称为超级写实主义,理查德·埃斯蒂斯(Richard Estes)、丹尼斯·彼得森、奥黛丽·弗拉克(Audrey Flack)和唐埃迪等画家通常从摄影工作开始,如今依然创作类似照片的绘画。”[5]

然而,20世纪末期,超级写实主义和传统的照相写实主义处理方式形成对比。[6]超级写实主义的画家和雕塑家使用照片作为参考,创造一个更加明确和详细的渲染的作品,不像照相写实主义,往往直接的叙述和描写。照相写实主义画家希望模仿照片,为了符合照片整体设计,常常省略或者抽象一些细节。[7][8]他们经常省略人物的表情、政治价值和叙述元素。照相写实主义风格演变自波普艺术,作品通常紧凑精致,线条分明,突出重点。[9]

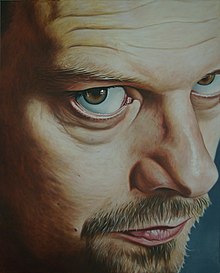

超级写实主义则与之相反,虽然本质上参考照片,常常对描绘的主题处理得更柔软更复杂,使之表现成一个生动的对象。超级写实主义作品中的对象和场景描绘得非常精致,创造出原始照片中没有的一个新的现实的幻想。这并不是说他们是超现实主义,因为这种幻想是一个令人信服的描写现实。纹理、表面、灯光效果和阴影画表现得清晰,比参考照片甚至实物还要鲜明。[10]

超级写实主义的哲学根源自让·鲍德里亚的理论,“模拟的东西永远不在现实中存在”。( the simulation of something which never really existed.)[11]因此,超级写实主义创建了一个虚假的现实,是一个令人信服的幻想,是基于现实的一个模拟。超级写实主义绘画和雕塑作品是数码相机拍出并在计算机上显示的超级高分辨率的照片的副产品。就如照相写实主义效仿模拟摄影,超级写实主义利用数码照片并扩展之来创造一个新的现实的感觉。[12][2] 超级写实主义绘画和雕塑使观众得到高清晰度图像的幻觉,但是比图像更细致。[13]

风格和方式

[编辑]

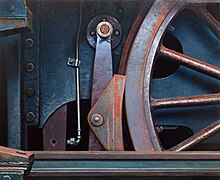

超级写实主义的绘画和雕塑通过微妙的灯光和阴影效果,创造出有形固态和实际存在感觉。[14]超级写实主义的绘画作品往往是原始参考照片的10倍或者20倍,但保留了极高的色彩分辨率,精确度和细节。许多作品通过喷笔实现,用丙烯酸树脂、油或两者兼而有之。Ron Mueck的生动的雕塑作品比实际对象大很多,通过对聚酯树脂和多种模具的细致使用,使作品细节非常有说服力。

超级写实主义作品更多地关注细节和对象。超级写实主义绘画和雕塑作品并不是照片的严格诠释,也不是某一个场景或主题的文字插图。相反,它们利用其他的,往往是微妙的绘画元素来创造实际上不存在或者人的眼睛不能看到的现实幻觉。[15]此外,它们可能包括情感、社会、文化和政治主题要素作为视觉错觉的扩展,与照相写实主义有所不同。[16]

超级写实主义画家和雕塑家使用一些机械方式使图像转移到画布或者模具上,包括预描或打底和制模。幻灯片投影仪或者多媒体投影仪将图片投射到画布,网格等基本技术也被应用来确保精确性。[17]雕塑采用聚酯直接应用到人体或模具。超级写实主义需要高超的技术和精湛的技巧来模拟一个虚假的现实。因此,作品往往结合并利用摄影的局限,如景深、透视和焦点范围。数字照片会出现一些异常,如碎片,一些画家也利用这一点来强调其数字源,如查克·克洛斯、丹尼斯·彼得森等。[18]

主题

[编辑]超级写实主义作品对象包括画像、具象艺术、景物、风景、城市风景和叙事场面。近期由于对细节的描写和对社会、文化或者政治主题重视,超级写实主义风格比照相写实主义更加文学性。新的照相写实主义延续避免照片异常,因此两者形成鲜明对比。超级写实主义画家模拟并提高精确的摄影照片,在社会和文化的背景下,使之产生有光学说服力的现实幻象。[19][20]

有些超级写实主义艺术家通过遗留的仇恨和不容忍叙述描写,揭露极权主义政权和第三次世界军事政府。[21]丹尼斯·彼得森、戈特弗里德·郝文和Latif Maulan在作品中描述了社会腐朽的政治和文化偏差。丹尼斯·彼得森作品关注散居的犹太人、种族灭绝和难民。[22][23]郝文对发展了一种非常规的叙事方式,作品针对犹太人大屠杀的过去、现在和未来的思考。Latif Maulan的作品主要批评社会对弱势群体的无视。[24]主题包括种族灭绝的图像,其悲惨的后果和思想意识的结果。[25] [26]这些有争议的艺术家通过作品激进地对抗人权状态。[27]这些栩栩如生的作品是对人类的荒诞行为的历史评论。[28] [29]

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ Bredekamp, Horst, Hyperrealism - One Step Beyond. Tate Museum, Publishers, UK. 2006. p. 1

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Thompson, Graham: American Culture in the 1980s (Twentieth Century American Culture) Edinburgh University Press, 2007 P. 77-79

- ^ Jean-Pierre Criqui, Jean-Claude Lebensztejn interview, Artforum International, June 1, 2003

- ^ Robert Bechtle: A Retrospective by Michael Auping, Janet Bishop, Charles Ray, and Jonathan Weinberg. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA,(2005). ISBN 978-0-520-24543-3

- ^ Thompson, Graham: American Culture in the 1980s (Twentieth Century American Culture) Edinburgh University Press, 2007 P. 78

- ^ Mayo, Deborah G., 1996, Error and the Growth of Experimental Knowledge, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. P. 57-72

- ^ Chase, Linda, Photorealism at the Millennium, The Not-So-Innocent Eye: Photorealism in Context. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 2002. pp 14-15.

- ^ Nochlin, Linda, The Realist Criminal and the Abstract Law II, Art In America. 61 (November - December 1973), P. 98.

- ^ New Britain Museum of American Art - Educational Resources 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2007-03-13.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 12.

- ^ Jean Baudrillard, "Simulacra and Simulation", Ann Arbor Mich.: University of Michigan Press, 1981

- ^ Horrocks, Chris and Zoran Jevtic. Baudrillard For Beginners. Cambridge: Icon Books, 1996. p. 80-84

- ^ Bredekamp, Horst, Hyperrealism - One Step Beyond. Tate Museum, Publishers, UK. 2006. p. 1-4.

- ^ Daniel Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1992). Random House ISBN 978-0-679-74180-0

- ^ Fleming, John and Honour, Hugh The Visual Arts: A History, 3rd Edition. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 1991. p. 680-710

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980.

- ^ Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 1980. p. 12-13.

- ^ Battock, Gregory. Preface to Photorealism. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York, 1980. pp 8-10.

- ^ Petra Halkes, "A Fable in Pixels and Paint - Gottfried Helnwein's American Prayer". Image & Imagination, Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-7735-2969-1)

- ^ Alicia Miller, "The Darker Side of Playland: Childhood Imagery from the Logan Collection at SFMOMA", Artweek, US, Nov 1, 2000

- ^ Jean Baudrillard, "The Precession of Simulacra", in Media and Cultural Studies : Keyworks, Durham & Kellner, eds. ISBN 0-631-22096-8

- ^ Thompson, Graham: American Culture in the 1980s Edinburgh University Press, 2007 P. 77-79

- ^ Robert Ayers, Art Critic,“Art Without Edges: Images of Genocide in Lower Manhattan”, Art Info June 2, 2006 存档副本. [2007-04-29]. (原始内容存档于2007-05-04).

- ^ Daniel Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1992). ISBN 978-0-679-74180-0

- ^ Christoper Ashley, Denis Peterson - Don't Shed No Tears", [1] 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2007-05-02.

- ^ Julia Pascal, "Nazi Dreaming", New Statesman, UK, April 10, 2006 [2] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ George Ritzer, The McDonaldization of Society (2004). ISBN 978-0-7619-8812-0

- ^ Christoper Rywalt, "Denis Peterson", NYC Art, June 7, 2006 [3] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Robert Flynn Johnson, Curator in Charge, "The Child - Works by Gottfried Helnwein", California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, ISBN 0-88401-112-7, 2004

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.