秀丽隐杆线虫

| 秀丽隐杆线虫 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 秀丽隐杆线虫 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 线虫动物门 Nematoda |

| 纲: | 色矛纲 Chromadorea |

| 目: | 小杆目 Rhabditida |

| 科: | 小杆线虫科 Rhabditidae |

| 属: | 隐杆线虫属 Caenorhabditis |

| 种: | 秀丽隐杆线虫 C. elegans

|

| 二名法 | |

| Caenorhabditis elegans Maupas, 1900

| |

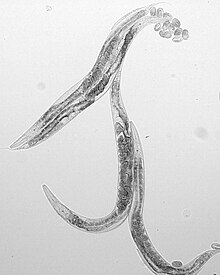

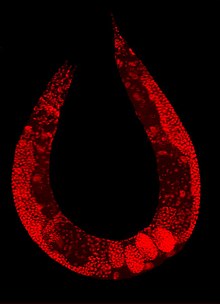

秀丽隐杆线虫(学名:Caenorhabditis elegans)是一种非寄生性线虫,身体透明,长度约1毫米,主要分布在温带地区的土壤中。其寿命约两至三周,其中发育时间在三天左右,分为胚胎期、幼虫期和成虫期。

秀丽隐杆线虫有雄性和雌雄同体两种性别。自然条件下,雌雄同体虫占大多数,可自体受精,也可接受雄虫的精子产生后代。

自20世纪60年代,悉尼·布伦纳利用线虫研究细胞凋亡遗传调控的机制之后,秀丽隐杆线虫逐渐成为分子生物学和发育生物学研究领域中最常用的模式生物之一[1]。秀丽隐杆线虫具有固定且已知的细胞数量和发育过程,亦为第一种完成全基因组测序的多细胞真核生物,截至2019年,它是唯一完成连接组(connectome,神经元连接)测定的生物体[2][3][4]。

解剖特征

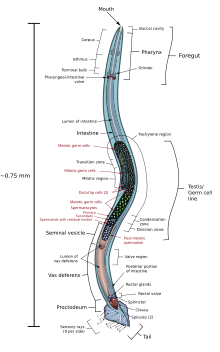

秀丽隐杆线虫的形态为蠕虫状、两侧对称,无分节,有四条主要的表皮索状组织(epidermal cord)及一个充满体液的假体腔(pseudocoelom)。这一科的成员大都有与其他动物相同的器官组织。牠们以微生物为食,如大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)等。秀丽隐杆线虫有雄性及雌雄同体两种性别,雌雄同体占大多数。基本解剖构造包括口、咽、肠、性腺,及胶原蛋白表皮层,此外两种性别的线虫还分别具有不同的生殖器官。雌雄同体虫和雄虫分别具有959和1031个体细胞,各细胞的位置和细胞渊源均已确定。[5]

秀丽隐杆线虫的上皮层(epidermis)由大型多核合胞体细胞组成,源自胚胎外胚层。上皮层在其上方可形成一层主要由胶原、脂质、糖蛋白组成的表皮(cuticle)[6]。这一层表皮是线虫具有保护作用的外骨架,是其维持形态所必需的结构,并且可为肌肉收缩提供固定位点[7][8]。

上皮层下方是体壁肌,分为四个肌肉带,共95个细胞[9]。腹部、背部两侧肌肉的规律性收缩使得线虫的运动呈正弦状,该生物名称中的“秀丽”即取自于此。体壁肌呈条纹状,有多个肌节,由单核细胞组成。此外,咽部还有八层共20个肌细胞,与表皮相连。头部另有一个肌细胞,起到联系腹部、背部体壁肌组织的作用[10]。

消化系统由咽、肠等构成。咽部(pharynx)为一个神经-肌肉泵,吸入细菌并将其送入肠道中,含有20个相对独立于全身神经系统的神经细胞。咽传送食物的效率与食物质量和线虫的饱足/饥饿状态有关[11]。咽部通过一个类似阀的结构与肠(intestine)相连,肠道末端又与直肠(rectum)相连。秀丽隐杆线虫的肠主要包括20个多倍体细胞,表面覆盖有大量微绒毛,作用为分泌消化酶,以及储存脂质、蛋白质等[9]。

线虫肠道壁细胞中有大量颗粒状结构,称为肠颗粒(gut granules),这一结构也存在于小杆目其他物种体内。肠颗粒内部为酸性环境,参与内吞作用,与溶酶体相似,但体积更大。在紫外光激发下,这些颗粒状物体可发射蓝色荧光,在线虫死后尤为明显。对其作用的猜测包括用于储存、防御病毒、紫外光下的保护作用等。[12]

秀丽隐杆线虫的神经系统含有302个(雌雄同体)或383个(雄虫)神经元,其胞体主要位于头部、腹部和背部的神经节中。大多数神经元的结构比较简单,只含有1个或2个无分支的神经突,但也有部分结构复杂的感觉神经元。线虫也有类似神经胶质细胞的辅助细胞,不过数量不及脊椎动物。突触总数在7000以上,主要分布在头部、背部、腹部、尾部的四个区域中,大多是由两个并排的神经突在交叉处形成,与脊椎动物中常见的结构不同。秀丽隐杆线虫使用多种常见的神经递质,如乙酰胆碱、谷氨酸、γ-氨基丁酸、多巴胺和血清素等。间隙连接则与其他无脊椎动物一样,由无脊椎动物连接蛋白形成。[13][14]

雌雄同体虫的生殖器官包括排卵口和性腺。排卵口位于腹侧中心,是排卵和雄虫精子进入的通道。雌雄同体虫的性腺包括两个U形管状的臂,每个臂从远端到排卵口可依次分为卵巢、环形区、输卵管、储精囊、球形瓣膜和子宫等区域。生殖细胞在卵巢远端产生,在进入环形区时达减数分裂双线期,在输卵管中达终变期。同时,精子储存于储精囊表面,在卵母细胞进入储精囊后发生受精作用。受精卵随后进入子宫,并由子宫和排卵口的肌肉推出体外。不同于哺乳动物,线虫精子的形态不固定,没有鞭毛和顶体等结构[15]。雄虫的生殖器官包括性腺和用于交配的尾。精子在精巢中产生,在精囊中成熟,并在交配时由输精管输送至尾部的泄殖腔。[9][16][17]

生命周期

秀丽隐杆线虫基本的生命周期如下:线虫由雌雄同体产下卵。卵在孵化后,会经历四个幼虫期(L1-L4)。当族群拥挤或食物不足时,幼虫会进入另一状态,即耐久型幼虫(dauer larva),其具有很强的抗逆性,而且难以老化。雌雄同体在L4期生产精子、并在成虫期产卵。秀丽隐杆线虫的性别决定为X0型,雄性能使雌雄同体受精;雌雄同体会优先选择雄性的精子。秀丽隐杆线虫在22°C的最适情况下,平均寿命约为二、三周,而发育时间只须几天。

胚胎期

胚胎发生可以大致分成两个时期:增殖期和型态形成期[19]。在增殖期受精卵会从一个细胞逐渐增殖成大约550个必要的未分化细胞,而增殖期又可以分为两个阶段,其中一个阶段为子宫内发育(在22°C的生长环境下约为受精后0-150分钟),在胚胎达到30个细胞时卵排出母体[20]。子宫外发育阶段则进行大量的细胞分裂和原肠形成(在22°C的生长环境下约为受精后150-350分钟),这个阶段持续到胚胎进入型态形成期[21]。在增殖期结束时,胚胎形成一个含有三胚层的球型构造,这三个胚层分别是外胚层(之后分化生成上皮组织和神经系统)、中胚层(未来产生咽部和肌肉系统)和内胚层(以后生成生殖腺和肠道)[20]。

在22°C的生长环境下,形态形成期约为受精后的5.5-5.6小时到12-14小时,胚胎会增长约三倍并形成完全分化的组织和器官。根据胚胎内观察到的虫体折叠数,这一阶段一般分为间歇期、1.5折叠期、2折叠期、3折叠期以及4折叠期。第一次的肌肉抽动在受精后430分钟可以观察到(约为1.5折叠或2折叠期);在受精后约510分钟可以观察到不同性别的发育差异——雌雄间性胚胎的头部伴护神经(cephalic companion neurons)死亡,雄性胚胎的雌雄间性特有神经(hermaphrodite-specific neurons)死亡,而在3折叠期的晚期;虫体运动神经系统已发育且可以在卵中沿其长轴进行移动;而在4折叠期时(第一次细胞分裂后约760分钟)胚胎的咽部开始进行收缩抽动;在第一次细胞分裂后约800分钟孵化。[19][22]

幼虫期

胚后发育期在孵化后食物刺激下启动。在有食物的情况下,细胞分裂持续,胚后发育开始于孵化后的三个小时[23],一般而言秀丽隐杆线虫经历四个阶段的幼虫期(L1、L2、L3、L4)后变成成体[24]。在这四个阶段的幼虫期中,许多在胚胎期出现的胚细胞以几乎不变的模式进行分裂。而在胚胎期所产生的671个细胞核中,有113个细胞会在胚后发育的过程进行细胞凋亡,而剩下的558个细胞中只有百分之十的细胞(雌雄间性有51个细胞,雄性有55个细胞)可以进一步分裂[25]。

倘若胚胎孵化后没有食物的供应,这些刚孵化的幼虫会停止继续发育并停留在这个阶段,直到有食物提供为止。这些停止继续发育的幼虫细胞会停留在细胞周期的G1期(停止生长)且无法进行分裂。幼虫在没有食物供应的情况下约可存活六到十天。[26][27]

在L2幼虫期的末期,如果环境状况不适合继续生长的话,秀丽隐杆线虫的幼虫可能会进入耐久型幼虫阶段[28]。这些不适合生长的环境状况包括环境激素影响、食物匮乏、高温等,可促使幼虫进入L2d幼虫阶段,这个阶段幼虫同时具有可以继续进入L3幼虫期或耐久型幼虫期的潜力,若环境逆境太强则进入耐久期,若环境转好则进入L3幼虫期,而耐久期为一个不会衰老的状态,因为其长短并不会影响阶段结束后的虫体寿命。在取得食物供应后的一个小时内,幼虫脱离耐久期,二到三个小时之后开始进食,在十个小时后会进入L4幼虫期。[29][30][31]

成虫期

在22°C到25°C的环境下,线虫在孵化后约45-50小时就会成为成熟的雌雄同体并产下第一个卵。成虫大约可以产生四天的卵细胞,此后成体会另外再存活十到十五天。进入成虫期前,雌雄同体的精子已产生完毕,每个性腺中约有150个。这些精子与卵母细胞一同储存,直到第一次排卵时,卵母细胞将精子推入储精囊中[32]。限于精子数量,自体受精的雌雄同体一共可产生大约300个后代,但是如果有雄性存在,雌雄间性会优先采用雄性的精子,此时后代数目可以增加到1200-1400个。雄性则在进入成虫期后的六天内具有和雌雄间性交配的能力,且大概可以产生3000个后代。[17]

进入成虫期后,线虫的体细胞不再发生细胞分裂,数目固定。成虫期线虫的生长仅是细胞体积增大的结果。[33]

基因组学

秀丽隐杆线虫是第一种完成全基因组测序的多细胞生物,其测序结果于1998年首次发表[34]。仍存在的一些小缺口于2002年10月前测序完成[35]。基因组包含6个染色体,约1亿个碱基对,编码约20,470个蛋白[36][37][38]。此后,部分基因组序列进行过一些修正,不过范围都在数千个碱基对以内[39]。

大小和基因含量

秀丽隐杆线虫基因组长度大约有1亿碱基对,由六条染色体和一条线粒体基因组组成。其基因密度约为每一个基因有五个千碱基对(kbp)。秀丽隐杆线虫的基因组中,内含子占26%,基因间区段占47%。据估计,全基因组中的非编码RNA基因在16,000种左右[40],很大一部分编码的是piRNA[41]。许多基因排列成簇,其中含有大量的操纵子序列,数量尚不清楚[42]。在真核生物中,线虫是少数基因组中含操纵子的生物之一,其他例子包括吸虫和扁形动物等[43]。

蛋白编码基因

基因组包含大约20,470个蛋白质编码基因[44]。约35%基因在人类基因组中有同源基因[34]。

有关的基因组

2003年以来,双桅隐杆线虫的基因组测序全部完成,开启了同属内的比较基因组学研究[45]。此后,研究者也已经利用鸟枪法技术研究了来自相同属的更多线虫的基因组序列的测序结果[46],例如腐生水果线虫(C. remanei)[47]、日本隐杆线虫(C. japonica)[48],和布伦纳隐杆线虫(C. brenneri,以布伦纳的名字命名)。目前隐杆线虫属已是基因组信息较为完备的一属。

生态学

尽管秀丽隐杆线虫是实验室中常用的一种模式生物,此物种在野生环境下的生活状态仍不清楚[49]。自然条件下,隐杆线虫属的各物种大多分布在温带地区富营养、细菌含量高的土壤环境中,以腐烂有机物质上的细菌为食。秀丽隐杆线虫可以食用多种常见于其生存环境的细菌,但一般的土壤条件仍不足以支持数量上可自我延续的种群。事实上,实验室使用的线虫多采自花园、堆肥等人工环境[50]。近期,有研究发现秀丽隐杆线虫在其他类型的有机物质,尤其是腐烂水果上面,可以大量生存,这很可能是自然条件下这种线虫的主要生活环境之一[49]。

不利环境下形成的耐久型幼虫可以借由部分倍足纲、昆虫纲、软甲纲或腹足纲动物所携带,前往宜居环境活动,说明了自然条件下可能存在相应的共生关系[50]。和土壤中的其他线虫一样,秀丽隐杆线虫可为捕食性线虫所捕食,也可让一些杂食性昆虫所食[51]。

研究与应用

发现历史

1900年,法国学者埃米勒·莫帕斯在阿尔及利亚的土壤中首次发现了秀丽隐杆线虫[52],并将其命名为elegans,意为“优雅”。1955年,这一物种归入隐杆线虫属中[53]。

悉尼·布伦纳于1963年提出以秀丽隐杆线虫做为模式生物,并于1974年发表了他利用线虫研究发育生物学及神经科学的成果。悉尼·布伦纳在该论文开篇便道:基因如何指定在高等生物中发现的复杂结构,是生物学中尚未解决的一大问题。他认为要了解基因和行为之间的关系,便要知道神经系统的结构,以及神经系统是如何发展的。为了要回答这两个问题,该模式生物要能在实验室中作遗传学研究,而其神经系统也要能够精确定义,布伦纳认为,作为多细胞真核生物的秀丽隐杆线虫正好符合此二条件。[1]

秀丽隐杆线虫成虫约长1毫米,室温下大约三天可以从卵生长为可受精的成虫,在实验室中以大肠杆菌为食,易于大量培养,每只成虫在生命周期里可产生约300只后代,适合作遗传学研究。此外,培养秀丽隐杆线虫成本低,在实验室中容易掌控,并且可以在不用时冷冻,解冻之后仍能存活,因此适合长时间储存。[54][55]

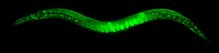

此外,秀丽隐杆线虫身体透明,在研究细胞分化及其他发育过程方面有特别的优势。每个体细胞如何发育都有详细的纪录,其细胞发育的命运在个体之间差异很小。秀丽隐杆线虫也是第一个基因组完全定序的多细胞生物。完成的基因组序列于1998年发表。秀丽隐杆线虫的基因组序列大约有一亿个碱基对,内含一万九千个以上的基因。2003年,同一属的双桅隐杆线虫也已完整定序了基因组,使得研究人员能够比对这两种生物的基因组。[45]

同时秀丽隐杆线虫神经系统相对简单,雌雄同体虫中,有302个神经元,约7000个突触。悉尼·布伦纳等人将线虫续列纵切,利用电子显微镜得到的影像,重建其神经系统,并在1986年发表雌雄同体各个神经元之间如何连结,成为世界上第一个,也是目前唯一的神经网络体[56]。雄性的身体后部神经系统也在2012年经过重建,助于科学家了解交配行为所需的神经系统结构[57]。许多神经生物学家在此之后,利用秀丽隐杆线虫做为模式生物,来了解其如何产生趋化性,趋温性等反应[58][59]。

21世纪以来,直接应用秀丽隐杆线虫进行的研究获得过三次诺贝尔奖,包括2002年[60]、2006年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[61][62]及2008年诺贝尔化学奖[63]。目前,线虫的研究已有Wormbase等在线数据库,其主要内容包括秀丽隐杆线虫及相关物种的基因组、蛋白质信息等[64]。

模式生物

布伦纳对细胞凋亡的研究是线虫作为模式生物的首次应用。秀丽隐杆线虫每一个体细胞的发育命运均已确定,几乎不存在个体差异[25][65]。因此,秀丽隐杆线虫发育过程中发生的细胞凋亡过程已经确定:雌雄同体虫的发育过程中,共有131个细胞凋亡,如果抑制这一过程,则它们大多将分化为神经元[5][66]。在研究细胞凋亡在基因层次上的机理时,这一特性有重要的优势。出于同样的原因,线虫在胚胎发育研究中具有优势。例如,其胚胎发育早期的细胞分裂,是目前理解最清楚的不对称细胞分裂案例之一[67]。

RNA干扰是干扰特定基因功能的一种方法[61],在秀丽隐杆线虫中尤为简便[68],大部分基因的功能都可以通过这种方式抑制[69]。浸入含RNA的转化液,或注射RNA进入体细胞或生殖细胞,都可以达到RNA干扰的效果。另一种常用的方法,是转化大肠杆菌使其表达与目的DNA互补的双链RNA,并用此大肠杆菌喂食线虫[69]。相比之下,隐杆线虫属的其他物种,及其他更高级的动物物种,就大多相对不易进行RNA干扰。例如,只有秀丽隐杆线虫等少数几种线虫可从食物中摄取干扰所需的RNA[70]。与这种差异相关的秀丽隐杆线虫基因已经发现[71]。

秀丽隐杆线虫适合于研究减数分裂。在性腺中,处于某一特定位置的生殖细胞,其减数分裂所处的阶段总是确定的[9]。此外,秀丽隐杆线虫有较高效的DNA修复机制,其生殖细胞在减数分裂中对辐射的抗性很强[72]。结合以自交为主的繁殖方式,线虫具有很强的适应性优势[73]。

秀丽隐杆线虫也常用于研究衰老。最初线虫在衰老机制研究的应用集中于遗传学方面。近年来,线虫也广泛用于研究饮食、外源激素等环境因素的影响、衰老相关疾病,以及寻找与衰老调控相关的药物等。[74][75]

此外,根据其组织的特征,秀丽隐杆线虫还适合于研究细胞外基质的合成、损伤修复和细胞融合等生理过程[14]。线虫还是已发现具有类似睡眠现象的最低等生物体,常用于动物睡眠研究[76]。

参阅

参考文献

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Brenner, S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans (PDF). Genetics. 1974, 77: 71–94 [2016-12-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2022-04-28).

- ^ White, J. G.; et al. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci.. 1986, 314 (1165): 1–340. Bibcode:1986RSPTB.314....1W. PMID 22462104. doi:10.1098/rstb.1986.0056.

- ^ White, J. G. Getting into the mind of a worm—a personal view. WormBook. 2013: 1–10. PMC 4781474

. PMID 23801597. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.158.1.

. PMID 23801597. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.158.1.

- ^ Jabr, F. The Connectome Debate: Is Mapping the Mind of a Worm Worth It?. Scientific American. 2012-10-02 [2014-01-18]. (原始内容存档于2012-11-12).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. Molecular Biology of the Cell 5th. Garland Science. 2007: 1321. ISBN 978-0-8153-4105-5.

- ^ Cox, G. N.; Kusch, M.; Edgar, R. S. Cuticle of Caenorhabditis elegans: its isolation and partial characterization. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1981, 90 (1) [2016-12-08]. doi:10.1083/jcb.90.1.7. (原始内容存档于2019-06-09).

- ^ Kramer, J. M.; Johnson, J. J.; et al. The sqt-1 gene of C. elegans encodes a collagen critical for organismal morphogenesis. Cell. 1988, 55 (4): 555–565 [2016-12-08]. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90214-0. (原始内容存档于2020-06-09).

- ^ Page, A. P.; Johnstone, I. L. The cuticle. Wormbook. 2007 [2016-12-08]. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.138.1. (原始内容存档于2020-11-27).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Sulston, J. The Anatomy. Wood, W.B. (编). The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1988: 81–122 [2016-12-08]. ISBN 0-87969-307-X. (原始内容存档于2018-09-27).

- ^ Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Riddle, R. L. , 编. C. elegans II 2nd. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1997: 417–420 [2016-12-08]. ISBN 0-87969-532-3. (原始内容存档于2021-04-20).

- ^ Avery, L.; Shtonda, B. B. Food transport in the C. elegans pharynx. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2003, 206: 2441–2457 [2016-12-08]. doi:10.1242/jeb.00433. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Coburn, C.; Gems, D. The mysterious case of the C. elegans gut granule: death fluorescence, anthranilic acid and the kynurenine pathway. Frontiers in Genetics. 2013, 4: 151 [2016-12-12]. PMC 3735983

. PMID 23967012. doi:10.3389/fgene.2013.00151. (原始内容存档于2022-04-12).

. PMID 23967012. doi:10.3389/fgene.2013.00151. (原始内容存档于2022-04-12).

- ^ Hall, D. D.; Lints, R.; Altun, Z. Nematode neurons: Anatomy and anatomical methods in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aamodt, E. (编). The neurobiology of C. elegans. London: Elsevier Academic Press. 2006: 2–5 [2016-12-08]. ISBN 0080478611. (原始内容存档于2020-12-23).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Corsi, A. K.; Wightman, .; Chalfie, M. A Transparent window into biology: A primer on Caenorhabditis elegans. Wormbook. 2015 [2016-12-08]. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.177.1. (原始内容存档于2020-11-11).

- ^ Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W.; Shimabukuro, K.; Miao, L. Transformation: how do nematode sperm become activated and crawl?. Protein Cell. 2012, 3 (10): 755–761 [2016-12-12]. PMC 4875351

. PMID 22903434. doi:10.1007/s13238-012-2936-2. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

. PMID 22903434. doi:10.1007/s13238-012-2936-2. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Hubbard, E. J.; Greenstein, D. The Caenorhabditis elegans gonad: a test tube for cell and developmental biology.. Developmental Dynamics. 2000, 218 (1): 2–22 [2016-12-08]. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<2::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-W. (原始内容存档于2019-06-04).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Hodgkin, J. Sexual Dimorphism and Sex Determination. Wood, W. B. (编). The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1988: 243–279 [2016-12-11]. ISBN 0-87969-307-X. (原始内容存档于2021-04-27).

- ^ Loer, C. M.; Kenyon, C. J. Serotonin-deficient mutants and male mating behavior in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1993, 13 (12): 5407–5417 [2016-12-11]. PMID 8254383. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Sulston, J. E.; Schierenberg, E.; White, J. G.; Thomson, J. N. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology. 1983, 100 (1): 64–119 [2016-12-11]. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. (原始内容存档于2018-10-02).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Wood, W. B. Embryology. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1988: 215–241 [2016-12-11]. ISBN 0-87969-307-X. (原始内容存档于2018-09-27).

- ^ Labouesse, M. Embryonic development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Brenner, S.; Miller, J. H. (编). Encyclopedia of Genetics 1st. Academic Press. 2001: 612–621. ISBN 978-0-12-227080-2.

- ^ Bird, A. F.; Bird, J. The Structure of Nematodes 2nd. Academic Press. 1991: 23–34 [2016-12-11]. ISBN 032313839X.

- ^ Ambros, V. Control of developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2000, 10 (4): 428–433 [2016-12-11]. PMID 10889059. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00108-8. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Byerly, L.; Cassada, R. C.; Russell, R. L. The life cycle of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: I. Wild-type growth and reproduction. Developmental Biology. 1976, 51 (1): 23–33 [2016-12-11]. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(76)90119-6. (原始内容存档于2018-10-02).

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Sulston, J. E.; Horvitz, H. R. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology. 1977, 56 (1): 110–56 [2016-12-09]. PMID 838129. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. (原始内容存档于2019-09-28).

- ^ Gems, D.; Sutton, A. J.; et al. Two pleiotropic classes of daf-2 mutation affect larval arrest, adult behavior, reproduction and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1998, 150 (1): 129–155 [2016-12-11]. PMC 1460297

. PMID 9725835. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

. PMID 9725835. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Johnson, T. E.; Mitchell, D. H.; Kline, S.; Kemal, R.; Foy, J. Arresting development arrests aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1984, 28 (1): 23–40 [2016-12-11]. PMID 6542614. doi:10.1016/0047-6374(84)90150-7. (原始内容存档于2018-10-02).

- ^ 線蟲相關中英名稱對照表. 2003 [2017-01-11]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-18).

- ^ Hu, P. J. Dauer. Wormbook. 2007 [2016-12-11]. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.144.1. (原始内容存档于2020-10-26).

- ^ Golden, J. W.; Riddle, D. L. The Caenorhabditis elegans dauer larva: Developmental effects of pheromone, food, and temperature. Developmental Biology. 1984, 102 (2): 368–378 [2016-12-11]. PMID 6706004. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(84)90201-X. (原始内容存档于2018-10-02).

- ^ Introduction to C. Elegans. C. Elegans as a model organism. Rutgers University. [2014-08-15]. (原始内容存档于2002-08-18).

- ^ Nayak, S.; Goree, J.; Schedl, T. fog-2 and the Evolution of Self-Fertile Hermaphroditism in Caenorhabditis. PLoS Biology. 2004, 3 (1): e6 [2016-12-12]. PMC 539060

. PMID 15630478. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030006. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

. PMID 15630478. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030006. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S.; Barnes, R. D. Invertebrate Zoology 7th. Cengage Learning. 2004: 753. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998, 282: 2012–2018 [2016-12-09]. PMID 9851916. doi:10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. (原始内容存档于2020-12-13).

- ^ Roundworm Genome Sequencing: Caenorhabditis species. NIH. [2016-12-14]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-23).

- ^ Release letter. Wormbase. [2016-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Bruce, B.; Johnson, A.; et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell 5th. Garland Science. 2007: 37. ISBN 978-0-8153-4105-5.

- ^ Hiller, L. W.; Coulson, A.; Murray, J. I.; Bao, Z.; Sulston, J. E.; Waterson, R. H. Genomics in C. elegans: so many genes, such a little worm 15 (12): 1651–1660. 2005 [2016-12-09]. PMID 16339362. doi:10.1101/gr.3729105. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Genome sequence changes. WormBase. 2011 [2016-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2019-10-17).

- ^ Stricklin, S. L.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Eddy, S. R. C. elegans noncoding RNA genes. WormBook. 2005 [2016-12-09]. PMID 18023116. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.1.1. (原始内容存档于2020-04-27).

- ^ Ruby, J. G.; Jan, C.; Player, C.; Axtell, M. J.; Lee, W.; Nusbaum, C.; Ge, H.; Bartel, D. P. Large-scale Sequencing Reveals 21U-RNAs and Additional MicroRNAs and Endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell. 2006, 127 (6): 1193–207 [2016-12-09]. PMID 17174894. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. (原始内容存档于2022-01-21).

- ^ Blumenthal, T.; Evans, D. A global analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans operons. Nature. 2005, 417: 851–854 [2016-12-09]. PMID 12075352. doi:10.1038/nature00831. (原始内容存档于2008-07-26).

- ^ Blumenthal, T. Operons in eukaryotes. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2004, 3 (3): 199–211 [2016-12-09]. PMID 15642184. (原始内容存档于2016-05-10).

- ^ WS227 Release Letter. WormBase. 10 August 2011 [2013-11-19]. (原始内容存档于2013-11-28).

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Stein, L. D.; et al. The Genome Sequence of Caenorhabditis briggsae: A Platform for Comparative Genomics. PLoS Biology. 2003, 1 (2): 166–192 [2016-12-09]. PMC 261899

. PMID 14624247. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0000045. (原始内容存档于2020-11-30).

. PMID 14624247. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0000045. (原始内容存档于2020-11-30).

- ^ UCSC genome browser. University of California Santa Cruz. [2016-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-23).

- ^ Genome Sequencing Center. Caenorhabditis remanei: Background. Washington University School of Medicine. [2008-07-11]. (原始内容存档于2008-06-16).

- ^ Genome Sequencing Center. Caenorhabditis japonica: Background. Washington University School of Medicine. [2008-07-11]. (原始内容存档于2008-06-26).

- ^ 49.0 49.1 Félix, M-A.; Braendle, A. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Current Biology. 2010, 20 (22): 965–969 [2016-12-10]. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.050. (原始内容存档于2013-08-22).

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Kiontke, K.; Sudhaus, W. Ecology of Caenorhabditis species. Wormbook. 2006 [2016-12-09]. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.37.1. (原始内容存档于2016-11-03).

- ^ Ingham, E. R. Soil Nematodes. Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. [2016-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-22).

- ^ Maupas, É. Modes et formes de reproduction des nematodes. Archives de Zoologie Experimentale et Generale. 1900, 8: 483–624.

- ^ Caenorhabditis elegans. University of California Davis. [2016-12-10]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-09).

- ^ Corsi, A. K. A biochemist's guide to Caenorhabditis elegans. Analytical Biochemistry. 2006, 359 (1): 1–17 [2016-12-11]. PMC 1855192

. PMID 16942745. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2006.07.033. (原始内容存档于2022-05-31).

. PMID 16942745. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2006.07.033. (原始内容存档于2022-05-31).

- ^ Stiernagle, T. Maintenance of C. elegans. Wormbook. 2006 [2016-12-09]. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1. (原始内容存档于2021-01-26).

- ^ White, J. G.; Southgate, E.; Thomson, J. N.; Brenner, S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans 314 (1165): 1–340. 1986 [2016-12-09]. PMID 22462104. (原始内容存档于2019-10-16).

- ^ Jarrell, T. A.; et al. The connectome of a decision-making neural network (PDF). Science. 2012, 337: 437–444 [2012-10-06]. doi:10.1126/science.1221762.

- ^ Dunn, N. A.; Lockery, S. R.; Pierce-Shimomura, J. T.; Conery, J. S. A Neural Network Model of Chemotaxis Predicts Functions of Synaptic Connections in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Computational Neuroscience. 2004, 17 (2): 137–147 [2016-12-14]. doi:10.1023/B:JCNS.0000037679.42570.d5. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Hedgecock, E. M.; Russell, R. L. Normal and mutant thermotaxis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. PNAS. 1975, 72 (10): 4061–4065 [2016-12-14]. PMID 1060088. (原始内容存档于2020-12-23).

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2002. www.nobelprize.org. [2016-12-10]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-15).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Fire, A.; Xu, S.; et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998, 391: 806–811 [2016-12-12]. PMID 9486653. doi:10.1038/35888. (原始内容存档于2017-06-09).

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2006. www.nobelprize.org. [2016-12-10]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-15).

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008. www.nobelprize.org. [2016-12-10]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-15).

- ^ Harris, T. W.; Antoshechkin, I.; et al. WormBase: a comprehensive resource for nematode research. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010, 38: 463–467 [2016-12-10]. PMC 2808986

. PMID 19910365.

. PMID 19910365.

- ^ Kimble, J.; Hirsh, D. The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology. 1979, 70 (2): 396–417 [2016-12-09]. PMID 478167. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(79)90035-6.

- ^ Peden, E. Cell death specification in C. elegans. Cell Cycle. 2008, 7 (16): 2479–2484 [2016-12-09]. PMC 2651394

. PMID 18719375. doi:10.4161/cc.7.16.6479. (原始内容存档于2022-04-12).

. PMID 18719375. doi:10.4161/cc.7.16.6479. (原始内容存档于2022-04-12).

- ^ Gönczy, P. Asymmetric cell division and axis formation in the embryo. WormBook. 2005 [2016-12-09]. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.30.1. (原始内容存档于2020-02-24).

- ^ Fortunato, A.; Fraser, A. G. Uncover genetic interaction in Caenorhabditis elegans by RNA interference (PDF). Bioscience Reports. 2005, 25: 299–307 [2016-12-09]. PMID 16307378. doi:10.1007/s10540-005-2892-7.

- ^ 69.0 69.1 Kamath, R. S.; et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003, 421: 231–237 [2016-12-09]. PMID 12529635. doi:10.1038/nature01278. (原始内容存档于2011-07-19).

- ^ Félix, M-A. RNA interference in nematodes and the chance that favored Sydney Brenner. Journal of Biology. 2008, 7 (9): 34–56 [2016-12-09]. PMC 2776389

. PMID 19014674. doi:10.1186/jbiol97. (原始内容存档于2021-01-20).

. PMID 19014674. doi:10.1186/jbiol97. (原始内容存档于2021-01-20).

- ^ Winston, W. M.; Sutherlin, M.; Wright, A. J.; Feinberg, E. H.; Hunter, C. P. Caenorhabditis elegans SID-2 is required for environmental RNA interference. PNAS. 2007, 104 (25): 10565-10570 [2016-12-09]. PMC 1965553

. PMID 17563372. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611282104. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

. PMID 17563372. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611282104. (原始内容存档于2020-08-02).

- ^ Takanami, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Efficient repair of DNA damage induced by heavy ion particles in meiotic prophase I nuclei of Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Radiation Research. 2003, 44 (3): 271–276 [2016-12-09]. PMID 14646232. doi:10.1269/jrr.44.271.

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Bernstein, C. Evolutionary Origin and Adaptive Function of Meiosis. Meiosis. InTech. [2016-12-09]. ISBN 978-953-51-1197-9. (原始内容存档于2018-07-05).

- ^ Olsen, A.; Vantipalli, M. C.; Lithgow, G. J. Using Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for aging and age-related diseases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006, 1067: 120–128 [2016-12-09]. PMID 16803977. doi:10.1196/annals.1354.015. (原始内容存档于2017-03-05).

- ^ Johnson, T. E. Caenorhabditis elegans 2007: The premier model for the study of aging. Experimental Gerontology. 2008, 43 (1): 1–4 [2016-12-09]. PMID 17977684. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2007.09.008. (原始内容存档于2018-10-02).

- ^ Iwanir, S.; Tramm, N.; Nagy, S.; Wright, C.; Ish, D.; Biron, D. The microarchitecture of C. elegans behavior during lethargus: homeostatic bout dynamics, a typical body posture, and regulation by a central neuron. Sleep. 2013, 36 (3): 385–395 [2016-12-12]. PMC 3571756

. PMID 23449971. doi:10.5665/sleep.2456. (原始内容存档于2016-12-20).

. PMID 23449971. doi:10.5665/sleep.2456. (原始内容存档于2016-12-20).

- ^ 生命暫停 46,000 年後,從永凍土解凍的古代線蟲成功復活. 科技新报. [2023-12-12]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-12).

延伸阅读

- Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Riddle, D. L.; et al , 编. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1997. ISBN 0-87969-532-3.

- Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Wood, W. B. , 编. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1988. ISBN 0-87969-307-X.

- Hope, I. A. (编). C. elegans: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press. 1999. ISBN 9780199637386.

- Bird, A. F.; Bird, J. The Structure of Nematodes 2e. Academic Press. 1991. ISBN 978-0-12-099651-3.

- Epstein, H. F.; Shakes, D. C. (编). Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press. 1995. ISBN 0125641494.

外部链接

- WormBase,秀丽隐杆线虫遗传学和基因组数据库。

- WormAtlas (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆),秀丽隐杆线虫行为学和解剖结构数据库。

- WormBook (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆),秀丽隐杆线虫综述集。

- AceView WormGenes (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆),美国国家生物技术信息中心(NCBI)出版的线虫基因组数据库。

- WormWeb (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆),用于分析线虫神经网络体、细胞渊源等特性的工具。

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.