ウイルス潜伏

・侵入

・複製

・潜伏

・排出

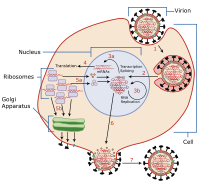

ウイルス潜伏 (英: virus latency または 英: viral latency) は、病原性ウイルスが細胞内で休眠 (潜伏) する能力であり、ウイルスのライフサイクルの溶原性部分として知られている[1]。潜伏ウイルス感染症は、慢性ウイルス感染症とは区別される持続的なウイルス感染の一種である。潜伏期とは、特定のウイルスの生活環(ライフサイクル)において、最初の感染の後、ウイルス粒子の増殖が停止する段階のことである。しかし、ウイルスゲノムは根絶されていない。ウイルスは、宿主が外部の新しいウイルスに再感染することなく、宿主内に無期限に留まり、再活性化して大量のウイルス子孫 (ウイルスのライフサイクルの溶菌サイクル) の生成を開始することができる[2]。

ウイルス潜伏を、ウイルスが休眠していない潜伏期間 (英: incubation period) 中の臨床潜伏 (英: clinical latency) と混同すべきではない。

機構

[編集]エピソーム潜伏

[編集]エピソーム潜伏(英: episomal latency)とは、潜伏期に遺伝子エピソームを使用することを指す。この潜伏型では、ウイルス遺伝子は安定化され、細胞質または核内に線状構造またはラリアット構造の別個の物体として浮遊している。エピソーム潜伏は、プロウイルス潜伏よりもリボザイムや宿主外来遺伝子の分解に対して脆弱である (下記参照)。

一例として、ヘルペスウイルス科のヘルペスウイルスは、いずれも潜伏感染を確立する。ヘルペスウイルスには、水痘ウイルスおよび単純ヘルペスウイルス (HSV-1, HSV-2) が含まれ、これらはすべて、神経細胞においてエピソーム潜伏を確立し、線状遺伝物質を細胞質中に浮遊させる[3]。ガンマヘルペスウイルス亜科は、エプスタイン・バール・ウイルスの場合のB細胞など、免疫系の細胞で確立されたエピソーム潜伏と関連している[3][4]。エプスタイン・バール・ウイルスの溶菌再活性化 (これは化学療法または放射線が原因である可能性がある) は、ゲノム不安定性および癌(がん)を引き起こす可能性がある[5]。単純ヘルペス (HSV) の場合、ウイルスは神経節[6]や神経細胞などの神経細胞のDNAと融合することが示されており、HSVは、酸素や栄養が不足するとクロマチンがコンパクトになる (潜伏状態になる) が[7]、ストレスによってクロマチンがわずかに緩むだけでも再活性化する[8]。

サイトメガロウイルス (CMV) は骨髄系前駆細胞に潜伏し、炎症によって再活性化する[9]。免疫抑制や重篤疾患 (特に敗血症) では、CMVの再活性化が起こることが多い[10]。CMVの再活性化は、重度の大腸炎患者によく見られる[11]。

エピソーム潜伏の利点は、ウイルスが核に入る必要がなく、したがって核ドメイン10 (ND10)がその経路を介してインターフェロンを活性化することを回避できるという事実が含まれる。

欠点は、細胞防御へのより多くの曝露を含み、細胞酵素を介したウイルス遺伝子の分解の可能性につながる[12]。

再活性化は、ストレス、紫外線(UV)などが原因である可能性がある[13]。

プロウイルス潜伏

[編集]プロウイルス (英: provirus) とは、宿主細胞のDNAに組み込まれたウイルスゲノムのことである。

利点は、宿主細胞の自動分裂がウイルスの遺伝子の複製をもたらすこと、および細胞を殺さずに感染した細胞から組み込まれたプロウイルスを除去することはほぼ不可能であるという事実が含まれる。[14]

この方法の欠点は、核に入る必要があることである (そしてそれを可能にするタンパク質のパッケージングが必要である)。しかし、宿主細胞のゲノムに組み込まれたウイルスは、細胞が生きている限りそこに留まることができる。

これを行うウイルスとして最もよく研究されているのがHIVである。HIVは、逆転写酵素を使用してRNAゲノムのDNAコピーを作成する。HIVの潜伏によって、ウイルスは免疫系を大きく回避できる。潜伏する他のウイルスと同様に、潜伏している間は通常、症状を引き起こさない。残念ながら、プロウイルス潜伏期のHIVは、抗レトロウイルス薬で標的にすることはほぼ不可能である。

潜伏期間の維持

[編集]プロウイルスとエピソームの両方の潜伏は、継続的な感染とウイルス遺伝子の忠実度 (英: fidelity, フィディリティー) を保つために必要となることがある。潜伏は一般に、主に潜伏期に発現するウイルス遺伝子によって維持される。これらの潜伏関連遺伝子の発現は、ウイルスゲノムが細胞リボザイムによって消化されたり、免疫系によって発見されたりするのを防ぐように機能することがある。特定のウイルス遺伝子産物 (ノンコーディングRNAやタンパク質などのRNA転写物) もアポトーシスを阻害するか、細胞の増殖および分裂を誘発して、感染した細胞の複製をより多く生成できるようにする[15]。

このような遺伝子産物の例は、単純ヘルペスウイルスの潜伏関連転写物 (英: latency associated transcripts、LAT) があり、主要組織適合遺伝子複合体 (MHC) を含む多数の宿主因子を下方制御し、アポトーシス経路を阻害することによってアポトーシスを妨害する。

特定のタイプの潜伏期間は、内在性レトロウイルスに起因すると考えられている。これらのウイルスは、遠い過去にヒトゲノムに組み込まれ、現在は生殖によって感染している。一般に、これらのタイプのウイルスは高度に進化し、多くの遺伝子産物の発現を失っている[16]。これらのウイルスによって発現されるタンパク質の一部は、宿主細胞と共進化して、正常なプロセスで重要な役割を果たしている[17]。

派生症状

[編集]ウイルス潜伏は活発なウイルス排出を示さず、病理や症状を引き起こさないが、ウイルスは外部の活性化因子 (すなわち日光、ストレスなど) を介して再活性化し、急性感染を引き起こすことがある。一般に、生涯感染する単純ヘルペスウイルスの場合、ウイルスの血清型が時折再活性化して口唇ヘルペスを引き起こす。その痛みは免疫システムによって速やかに解消されるが、時折、小さな不快感になることがある。水痘帯状疱疹ウイルスの場合、最初の急性感染 (水痘) の後、ウイルスは帯状疱疹として再活性化されるまで休眠状態にある。

潜伏感染のより深刻な影響は、細胞を形質転換し、制御されていない細胞分裂を強制する可能性である。これは、ウイルスゲノムが宿主自身の遺伝子にランダムに挿入され、ウイルスの利益のために宿主細胞増殖因子が発現した結果である。注目すべき出来事としては、パリのネッケル小児病院でレトロウイルスベクターを使用した遺伝子治療中に、20人の少年が遺伝子疾患の治療を受け、その後5人が白血病様症候群を発症したことが挙げられる[18]。

これはヒトパピローマウイルスの感染症にも見られるもので、持続感染は細胞の悪性形質転換の結果として子宮頸がんを引き起こす可能性がある[19][20][21]。

HIV研究の分野では、特定の長寿細胞型におけるプロウイルス潜伏は、潜伏ウイルスの持続性を特徴とする場所 (細胞型または組織) を参照し、1つまたは複数のウイルスリザーバーの基礎の概念となる。具体的には、休止中のCD4陽性T細胞に複製能力のあるHIVが存在することにより、抗レトロウイルス薬への長期暴露にもかかわらず、このウイルスは進化することなく何年も存続することができる[22]。このHIVの潜在的な貯蔵所は、抗レトロウイルス治療がHIV感染症を治療することができない説明となるかもしれない[23][24][25]。

参照項目

[編集]脚注

[編集]- ^ Villarreal, Luis P. (2005). Viruses and the Evolution of Life. Washington, ASM Press.

- ^ N.J. Dimmock et al. "Introduction to Modern Virology, 6th edition." Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

- ^ a b Minarovits J (2006). “Epigenotypes of Latent Herpesvirus Genomes”. DNA Methylation: Development, Genetic Disease and Cancer. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 310. pp. 61–80. doi:10.1007/3-540-31181-5_5. ISBN 978-3-540-31180-5. PMID 16909907

- ^ “Influence of EBV on the peripheral blood memory B cell compartment”. Journal of Immunology 179 (5): 3153–60. (2007-09-01). doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3153. PMID 17709530.

- ^ “Epstein-Barr virus lytic reactivation regulation and its pathogenic role in carcinogenesis”. International Journal of Biological Sciences 12 (11): 1309–1318. (2016). doi:10.7150/ijbs.16564. PMC 5118777. PMID 27877083.

- ^ “Herpes Simplex Virus Establishment, Maintenance, and Reactivation: In Vitro Modeling of Latency”. Pathogens 6 (3): E28. (2017). doi:10.3390/pathogens6030028. PMC 5617985. PMID 28644417.

- ^ “Starve a Cell, Compact Its DNA - GEN”. GEN (2015年11月10日). 2020年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Discovery shows how herpes simplex virus reactivates in neurons to trigger disease” (2015年12月21日). 2020年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation: recent insights into an age old problem”. Reviews in Medical Virology 26 (2): 75–89. (2016). doi:10.1002/rmv.1862. PMC 5458136. PMID 26572645.

- ^ Cook CH (2007). “Cytomegalovirus reactivation in "immunocompetent" patients: a call for scientific prophylaxis”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 196 (9): 1273–1275. doi:10.1086/522433. PMID 17922387.

- ^ “Review article: cytomegalovirus and inflammatory bowel disease”. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 41 (8): 725–733. (2015). doi:10.1111/apt.13124. PMID 25684400.

- ^ “Gene delivery using herpes simplex virus vectors”. DNA Cell Biol 21 (12): 915–36. (Dec 2002). doi:10.1089/104454902762053864. PMID 12573050.

- ^ Preston, Chris M.; Efstathiou, Stacey (21 September 2018). “Molecular basis of HSV latency and reactivation”. In Arvin. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521827140. PMID 21348106

- ^ Marcello A. "Latency: the hidden HIV-1 challenge." Retrovirology. 2006 Jan 16;3(1):7

- ^ “A triple entente: virus, neurons, and CD8+ T cells maintain HSV-1 latency”. Immunol. Res. 36 (1–3): 119–26. (2006). doi:10.1385/ir:36:1:119. PMID 17337772.

- ^ Buzdin A (Nov 2007). “Human-specific endogenous retroviruses”. ScientificWorldJournal 7: 1848–68. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.270. PMC 5901341. PMID 18060323.

- ^ “An integrase of endogenous retrovirus is involved in maternal mitochondrial DNA inheritance of the human mammal”. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 366 (1): 206–211. (2007). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.127. PMID 18054325.

- ^ Hacein-Bey-Abina, S; Garrigue, A; Wang, GP; Soulier, J; Lim, A; Morillon, E; Clappier, E; Caccavelli, L et al. (September 2008). “Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1.”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 118 (9): 3132–42. doi:10.1172/JCI35700. PMC 2496963. PMID 18688285.

- ^ “Treating cancer as an infectious disease-viral antigens as novel targets for treatment and potential prevention of tumors of viral etiology”. PLOS ONE 2 (10): e1114. (Oct 2007). Bibcode: 2007PLoSO...2.1114W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001114. PMC 2040508. PMID 17971877.

- ^ Viral carcinogenesis in skin cancer. Current Problems in Dermatology. 35. (2007). 39–51. doi:10.1159/000106409. ISBN 978-3-8055-8313-8. PMID 17641489

- ^ “Viral infections as a cause of cancer (review)”. Int J Oncol 30 (6): 1521–8. (Jun 2007). doi:10.3892/ijo.30.6.1521. PMID 17487374.

- ^ “The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection”. Annu. Rev. Med. 53: 557–93. (2002). doi:10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104024. PMID 11818490.

- ^ “Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy”. Science 278 (5341): 1295–300. (November 1997). Bibcode: 1997Sci...278.1295F. doi:10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. PMID 9360927.

- ^ “A stable latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4(+) T lymphocytes in infected children”. J. Clin. Invest. 105 (7): 995–1003. (April 2000). doi:10.1172/JCI9006. PMC 377486. PMID 10749578.

- ^ “Latent reservoirs of HIV: obstacles to the eradication of virus”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (20): 10958–61. (September 1999). Bibcode: 1999PNAS...9610958C. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.20.10958. PMC 34225. PMID 10500107.

| 構成 | ||

|---|---|---|

| ライフサイクル | ||

| 遺伝学 | ||

| 宿主の別 | ||

| その他 | ||

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.