海洋温度

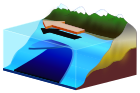

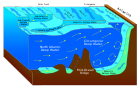

海洋温度(或称海水温度)取决于深度、地理位置及季节。不同地方的海水温度、盐度皆有所不同。通常,表层海水较深层海水温暖、盐度较高;[1]而在极地地区,深层的海水较为温暖,盐度也较高。[2]深层海水是海洋深处的寒冷咸水;这些海水温度均一,介于0-3°C[3]表层海水的温度则取决于落在其表面的太阳辐射量。在热带地区,太阳几乎直射,表层水温时常超过30 °C(86 °F);而在两极附近温度约是−2 °C(28 °F)。海水循环日以继夜,未曾间断。温盐环流是个由海水不同的的温度和盐度驱动的全球洋流循环系统。[4][5]温暖的表层洋流在远离热带时会变冷,水变得更稠密并下沉。在水温和密度变化的驱动下,冷水作为深海流流回赤道,最终再次涌向海面。

海洋温度一词可用于表述任何深度的海水温度,或专门用于不靠近表面的海洋温度(在这种情况下,它与“深海温度”同义)。

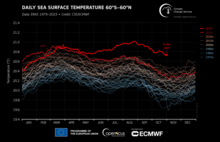

由于气候变化,海洋正在变暖,而且变暖的速度持续加快,[6]:9[7]变暖趋势遍及整个海洋。海洋表层(深度700米内)水温上升最快。2022年,全球海洋是人类有记录以来最热的一年。

定义与分区

海面温度

|

主条目:海面温度 |

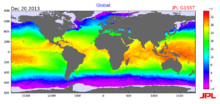

海面温度是指接近海洋表面的水温。对于表面的定义会有不同种的诠释,取决于检测方式,但通常是海面以下1毫米到20米之处。地球表面的气团会直接受到海面温度的影响而改变;天气亦是如此,例如造成海风和海雾。温暖的海面可能孕育热带气旋。

在全球暖化之际,海洋吸收了多余热量的92%,这也导致更多的暴风雨及洪水事件。[8]

深海温度

海面以下(通常只深度超过20米)的温度称为“海洋温度”或“深海温度”。海洋温度也会因地区和时间而异,并导致海洋热含量和海洋分层的变化。[9]气候变迁也提高了深海温度。[9]

海洋温度的影响

海洋温度和溶氧率是影响初级生产、海洋碳循环与海洋生态系的重要变因。[10]它们与盐度和密度共同扮演了海洋系统的重要角色,让海水混合或分层、产生洋流等。

海洋含热量

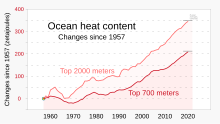

透过不同深度的海洋温度能计算出海洋热含量。

海洋热含量是指海洋吸收和储存的热能。为了计算海洋热含量,需要测量各地海洋不同位置和深度的温度,并积分整个海洋的热量面密度[注 1],即可得出海洋总热量。[12]1971年至2018年间,海洋热含量的增加占全球暖化导致的地球过剩热能的九成以上。[13][14]海洋热含量增加的主要因素是温室气体排放增加。[15]:1228截至2020年,大约三分之一的过剩热量已传播到700米以下的深海。[16][17]2022年世界海洋热含量超过了2021年的记录,再度成为历史记录中最热的水平。[18]在2019至2022年间,北太平洋、北大西洋、地中海和南冰洋这四个地区打破了六十多年来的最高热量观测结果。[19]海洋热含量和海平面上升是气候变化的重要指标。[20]

海水容易吸收太阳能,并且热容量远大于大气气体。[16] 因此,海洋顶部几米所包含的热能比整个地球大气层还多。[21]早在1960年以前,研究船和研究站便已开始在世界各地对海面温度和更深处的温度进行了采样。此外,自2000年以来,由近4000个机器人组成的Argo计划拓展了测量能力,更能呈现了温度异常的情况和海洋热含量的变化。已知至少自1990年以来,海洋热含量就不断稳定增长,甚至加速增长。[13][22]2003-2018年间,在深度小于2000米的区域内,平均每年增加9.3泽焦耳(这相当于 0.58±0.08 W/m2 的能量增长速率)。测量的不确定性主要是来自测量精度、空间覆盖范围,及持续数十年不间断测量的三方面挑战。[20]

海洋热含量的变化对地球的海洋和陆地生态系统皆产生深远的影响;当中包含对沿海生态系统的多重影响。直接影响包括海平面和海冰的变化、水循环强度的变化以及海洋生物的迁徙和灭绝。[23][24]测量

可以透过各种技术测量海洋温度。[25]在海面以下,温度测量与深度测量密不可分,因为温度会随深度变化而剧烈改变,特别是在弱风且日照强烈的白天。[26]

一个基本的技术是将CTD(温盐深仪)垂降到水面下以测量水温与其他资讯。[27]它透过导电电缆不断地将数据发送到船上。该设备通常安装在包括水采样瓶的框架上。自2010年代以来,自动驾驶装置(如微型潜水器等)越来越多。它们携带CTD传感器,但独立于研究船运行。

基本CTD系统可用于研究船(带有导电电缆)和无人装置甚至海狮。[28] 在最后一种情况下,数据必须通过遥测而不是电缆传回。

海面温度测量仅限于近表层。[29]它们可以用温度计或卫星光谱进行测量。1970年创建了第一颗全球复合卫星;1967年以来气象卫星已受到广泛应用。[30]

先进甚高分辨率辐射计(AVHRR)是从太空测量海面温度最常用的仪器。[25]:90

不同深度的海洋温度可以通过南森瓶、深海温度计、CTD或海洋声学断层扫描获得的测量结果估算而得。海面温度也可以系泊浮标和漂流浮标的测量,例如全球漂流者计划和国家数据浮标中心便有部署浮标。世界海洋数据库计划是最大的世界所有海洋温度剖面数据库。[31]

一个由“深海 Argo”浮标组成的小型测试舰队旨在将测量能力扩展到约 6000米深。完全部署后,它将准确采样大部分海洋空间的温度。[32][33]

水银温度计

热敏电阻和水银温度计被广泛部署在船舶和浮标上帮助测量海水温度。[25]:88水银温度计可以放置在船舷上方的桶中测量海水温度或放置在南森瓶上以测量更深层海水的温度。[25]:88

Argo 计划

Argo是一个海洋观测系统的名称,可为气候、天气、海洋学及渔业研究提供实时海洋观测数据。[34][35]

该观测系统由大量布放在全球海洋中小型、自由漂移的自动探测设备(Argo剖面浮标)组成。大部分浮标在1000米漂移(被称为停留深度),每隔10天下潜到2000米深度并上浮至海面,在这过程中进行海水温度和电导率等要素的测量,由此可计算获得海水盐度和密度。观测数据通过卫星传送到地面科研人员,并向所有人免费、无限制提供。Argo计划的名字起源于希腊神话中勇士伊阿宋(Jason)和阿尔戈英雄(Argonauts)寻找金色羊毛时所乘的船。之所以选用该名字,意在强调Argo计划与杰森卫星高度计的相互补充。Argo计划首先在1999年召开的海洋观测大会上提出,该会议是由国际机构组织的,旨在创建可协调的海洋观测方式。原始的 Argo 计划书(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) 由一个科学家组成的小组编写,该计划书描述了一个由3000个浮标组成的全球海洋观测网计划,并将在2007年的某时完成。2007年11月,由3000个浮标组成的全球海洋观测网全面建成。Argo指导工作组于1999年在美国马里兰召开了第一次会议,并在会上概述了全球数据共享原则。Argo指导工作组于2009年向海洋观测大会提交了十年进展报告[36] ,并收到了有关如何完善观测网的建议。这些建议包括在高纬度海区、边缘海(如墨西哥湾和地中海)和沿赤道海区加强观测,在西边界强流区(如墨西哥湾暖流和黑潮)强化观测,向深海扩展观测以及利用新型传感器监测海洋生物和化学变化等。2012年11月,Argo观测网已收集了100万条剖面(是20世纪所有调查船观测资料的两倍),并在多家组织的网站上进行了报道。[37][38]

海洋暖化

趋势

气候变化直接造成了海洋暖化的趋势。[41]:9从工业化前期到2011年至2020年十年间,海洋表面的温度已升高0.68至1.01°C。[9]:1214海洋温度持续上扬是地球能量不平衡不可避免的结果,而地球能量不平衡主要是由温室气体水平上升造成的。[42]

海洋上层(浅于700m)变暖速度最快。变暖趋势广泛,而大部分海洋热量增加发生在南冰洋。例如,20世纪50年代至80年代,南冰洋的温度上升了0.17°C,几乎是全球海洋上升速率的两倍。[43]

变暖速率随深度而变化:在一千米深处,全球变暖的速度约是每世纪0.4°C(数据来自 1981 年至 2019 年),是南冰洋的两倍。[44]:463

由于不同地区的水温不同,海洋总热量的变化更能呈现海洋变暖的趋势。与1969–1993年间相比,在1993至2017年间,海洋吸收了更多的热量。[44]:457

结果

这些观察到的变化的根本原因是人为排放的温室气体(例如二氧化碳和甲烷)。[45]这不可避免的导致海洋变暖,因为海洋吸收了气候系统中大部分额外的热量。[7]

换言之:海洋温度上升是地球能量收支不平衡的必然结果,主要与温室气体浓度增加有关。

主要物理效应

海洋分层增加和氧气含量降低

更高的气温导致海洋表面升温,暖水稳定维持在靠近表面的位置,海洋层之间的混合减少,同时减少上层了与寒冷深水的循环,进而使海洋层化增加。上下混合的减少减弱了海洋吸收热量的能力,因此未来更多的热量将集中到大气层和陆地中。热带气旋和其他风暴的能量可能增加,上层海洋中鱼类的养分将会减少,海洋储碳的能力也会降低。

水对氧气的溶解度随温度增加递减。层化现象使表面温度上升,溶氧量降低,也导致从表层水到深层水的供氧减少,从而进一步降低整体水域的氧气含量。[46] 这种现象称之为海洋低氧现象。海洋低氧区正不断扩张。[44]:471

洋流改变

洋流是由不同纬度的温度差异,以及盛行风和海水差异密度引起的。空气在赤道附近往往受到加热,因此升起,然后在稍微向极地的地方冷却,因此下沉。全球暖化改变了固有的空气循环系统和其他条件,进而影响洋流。[47]

海洋热浪

地质历史

基于岩石样本中氧和硅同位素,预测出前寒武纪海洋温度非常高。[50][51]35亿-20亿的海洋温度约是在55–85°C;而10亿年前温度下降到10到40°C。来自前寒武纪生物体的重建蛋白质也提供了证据,表明古代世界比今天温暖得多。[52][53]

寒武纪大爆发(大约 5.388 亿年前)是地球生命演化过程中的一个关键事件。这一事件发生时,海面温度预计将达到 60°C 左右。[54]这时的高温超出现代海洋无脊椎动物的承受范围,即38°C。[55]

而在1亿-6600万年前的白垩纪后期全球平均气文达到了过去约 2 亿年的最高水平。[56]

氧同位素数据库的数据表明,在多个地质时期,例如寒武纪后期、三叠纪前期、白垩纪后期和古新世-始新世过渡期间,发生了七次全球暖化事件。在这些变暖时期,海面温度比现在高出约 5–30 °C。[10]

参见

注解

参考文献

- ^ Ocean Stratification. The Climate System. Columbia Univ. [2015-09-22]. (原始内容存档于2020-03-29).

- ^ The Hidden Meltdown of Greenland. Nasa Science/Science News. NASA. [2015-09-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-31).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Temperature of Ocean Water. UCAR. [2012-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2010-03-27).

- ^ Rahmstorf, S. The concept of the thermohaline circulation (PDF). Nature. 2003, 421 (6924): 699 [2023-08-17]. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..699R. PMID 12610602. S2CID 4414604. doi:10.1038/421699a

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-02-14).

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-02-14).

- ^ Lappo, SS. On reason of the northward heat advection across the Equator in the South Pacific and Atlantic ocean. Study of Ocean and Atmosphere Interaction Processes (Moscow Department of Gidrometeoizdat (in Mandarin)). 1984: 125–9.

- ^ IPCC, 2019: Summary for Policymakers 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2022-10-18.. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-07-12. [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.001.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Hausfather, Zeke; Trenberth, Kevin E. How fast are the oceans warming?. Science. 2019, 363 (6423): 128–129 [2023-08-17]. Bibcode:2019Sci...363..128C. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30630919. S2CID 57825894. doi:10.1126/science.aav7619. (原始内容存档于2023-08-16) (英语).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 The Oceans Are Heating Up Faster Than Expected. scientific american. [2020-03-03]. (原始内容存档于2020-03-03).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2022-10-24.. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-08-09. [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Song, Haijun; Wignall, Paul B.; Song, Huyue; Dai, Xu; Chu, Daoliang. Seawater Temperature and Dissolved Oxygen over the Past 500 Million Years. Journal of Earth Science. 2019, 30 (2): 236–243 [2023-08-17]. ISSN 1674-487X. S2CID 146378272. doi:10.1007/s12583-018-1002-2. (原始内容存档于2023-08-17) (英语).

- ^ Top 700 meters: Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann. Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content. climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 6 September 2023. (原始内容存档于29 October 2023). ● Top 2000 meters: Ocean Warming / Latest Measurement: December 2022 / 345 (± 2) zettajoules since 1955. NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (原始内容存档于20 October 2023).

- ^ Kumar, M. Suresh; Kumar, A. Senthil; Ali, MM. Computation of Ocean Heat Content (PDF). Technical Report NRSC-SDAPSA-G&SPG-DEC-2014-TR-672 (National Remote Sensing Centre (ISRO), Government of India). 10 December 2014 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-04-12).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 von Schuckman, K.; Cheng, L.; Palmer, M. D.; Hansen, J.; et al. Heat stored in the Earth system: where does the energy go?. Earth System Science Data. 2020-09-07, 12 (3): 2013-2041. Bibcode:2020ESSD...12.2013V. doi:10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020

.

.

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Locarnini, Ricardo; et al. Upper Ocean Temperatures Hit Record High in 2020. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 2021, 38 (4): 523–530. Bibcode:2021AdAtS..38..523C. S2CID 231672261. doi:10.1007/s00376-021-0447-x

.

.

- ^ Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2022-10-24.. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-08-09. [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 LuAnn Dahlman and Rebecca Lindsey. Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2020-08-17 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-25).

- ^ Study: Deep Ocean Waters Trapping Vast Store of Heat. Climate Central. 2016 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-29).

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Mann, Michael E.; Zhu, Jiang; Wang, Fan; Locarnini, Ricardo; Li, Yuanlong; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong; Feng, Licheng. Another Year of Record Heat for the Oceans. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 2023, 40 (6): 963–974. Bibcode:2023AdAtS..40..963C. ISSN 0256-1530. PMC 9832248

. PMID 36643611. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2

. PMID 36643611. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2022, published online January 2023, Retrieved on July 25, 2023 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202213 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Cheng, Lijing; Foster, Grant; Hausfather, Zeke; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Abraham, John. Improved Quantification of the Rate of Ocean Warming. Journal of Climate. 2022, 35 (14): 4827–4840 [2023-08-23]. Bibcode:2022JCli...35.4827C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0895.1

. (原始内容存档于2017-10-16).

. (原始内容存档于2017-10-16).

- ^ Vital Signs of the Plant: Ocean Heat Content. NASA. [2021-11-15]. (原始内容存档于2022-11-22).

- ^ Abraham, J. P.; Baringer, M.; Bindoff, N. L.; Boyer, T.; et al. A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change. Reviews of Geophysics. 2013, 51 (3): 450–483. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..450A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.594.3698

. S2CID 53350907. doi:10.1002/rog.20022. hdl:11336/25416.

. S2CID 53350907. doi:10.1002/rog.20022. hdl:11336/25416.

- ^ Dean Roemmich. How long until ocean temperature goes up a few more degrees?. 斯克里普斯海洋研究所. 2014-03-18 [2023-08-17]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-01).

- ^ Ocean warming : causes, scale, effects and consequences. And why it should matter to everyone. Executive summary (PDF). 国际自然保护联盟. 2016 [2023-08-17]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-01-23).

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Introduction to Physical Oceanography. Open Textbook Library. 2008 [2022-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-26) (英语).

- ^ Vittorio Barale. Oceanography from Space: Revisited. Springer. 2010: 263 [2023-08-17]. ISBN 978-90-481-8680-8. (原始内容存档于2023-08-17).

- ^ Conductivity, Temperature, Depth (CTD) Sensors - Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. www.whoi.edu/. [2023-03-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-17) (美国英语).

- ^ Boyd, I.L; Hawker, E.J; Brandon, M.A; Staniland, I.J. Measurement of ocean temperatures using instruments carried by Antarctic fur seals. Journal of Marine Systems. 2001, 27 (4): 277–288 [2023-08-17]. doi:10.1016/S0924-7963(00)00073-7. (原始内容存档于2022-10-28) (英语).

- ^ Alexander Soloviev; Roger Lukas. The near-surface layer of the ocean: structure, dynamics and applications. The Near-Surface Layer of the Ocean: Structure (シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社). 2006: xi [2023-08-17]. Bibcode:2006nslo.book.....S. ISBN 978-1-4020-4052-8. (原始内容存档于2023-08-17).

- ^ P. Krishna Rao; W. L. Smith; R. Koffler. Global Sea-Surface Temperature Distribution Determined From an Environmental Satellite. Monthly Weather Review. January 1972, 100 (1): 10–14. Bibcode:1972MWRv..100...10K. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1972)100<0010:GSTDDF>2.3.CO;2

.

.

- ^ World Ocean Database Profiles the Ocean. National Centers for Environmental Information. 2017-06-14 [2023-08-17]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-26).

- ^ Administration, US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric. Deep Argo. oceantoday.noaa.gov. [2021-12-24]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-26) (美国英语).

- ^ Deep Argo: Diving for Answers in the Ocean's Abyss. www.climate.gov. 2021-12-24 [2023-08-17]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-02).

- ^ Argo Begins Systematic Global Probing of the Upper Oceans Toni Feder, Phys. Today 53, 50 (2000), (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) doi:10.1063/1.1292477

- ^ Richard Stenger. Flotilla of sensors to monitor world's oceans. CNN. September 19, 2000 [2007-10-28]. (原始内容存档于2007-11-06).

- ^ 存档副本 (PDF). [2013-09-02]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-10-17). Argo – 十年进展(提交至09海洋观测大会的白皮书)

- ^ http://www.bodc.ac.uk/about/news_and_events/argo_millionth_profile.html (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) 英国海洋数据中心祝贺100万条剖面。

- ^ http://www.unesco.org/new/en/media-services/single-view/news/argo_collects_its_one_millionth_observation/#.UiS-m9JwpyI (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) 联合国教科文组织祝贺100万条Argo剖面。

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Zhu, Jiang; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Locarnini, Ricardo; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong. Record-Setting Ocean Warmth Continued in 2019. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 2020, 37 (2): 137–142. Bibcode:2020AdAtS..37..137C. ISSN 1861-9533. S2CID 210157933. doi:10.1007/s00376-020-9283-7

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change. NASA. [2020-02-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-16).

- ^ "Summary for Policymakers". The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (PDF). 2019. pp. 3–36. doi:10.1017/9781009157964.001. ISBN 978-1-00-915796-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Mann, Michael E.; Zhu, Jiang; Wang, Fan; Locarnini, Ricardo; Li, Yuanlong; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong; Feng, Licheng. Another Year of Record Heat for the Oceans. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 2023: 1–12. ISSN 0256-1530. PMC 9832248

. PMID 36643611. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2

. PMID 36643611. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ Gille, Sarah T. Warming of the Southern Ocean Since the 1950s. Science. 2002-02-15, 295 (5558): 1275–1277. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1275G. PMID 11847337. S2CID 31434936. doi:10.1126/science.1065863.

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Bindoff, N.L., W.W.L. Cheung, J.G. Kairo, J. Arístegui, V.A. Guinder, R. Hallberg, N. Hilmi, N. Jiao, M.S. Karim, L. Levin, S. O'Donoghue, S.R. Purca Cuicapusa, B. Rinkevich, T. Suga, A. Tagliabue, and P. Williamson, 2019: Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2019-12-20.. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-07-12. [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In press.

- ^ Doney, Scott C.; Busch, D. Shallin; Cooley, Sarah R.; Kroeker, Kristy J. The Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Marine Ecosystems and Reliant Human Communities. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2020-10-17, 45 (1): 83–112. ISSN 1543-5938. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083019

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Chester, R.; Jickells, Tim. Chapter 9: Nutrients oxygen organic carbon and the carbon cycle in seawater 3rd. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley/Blackwell. 2012 [2023-08-17]. ISBN 978-1-118-34909-0. OCLC 781078031. (原始内容存档于2022-02-18).

- ^ Trenberth, K; Caron, J. Estimates of Meridional Atmosphere and Ocean Heat Transports. Journal of Climate. 2001, 14 (16): 3433–43 [2023-08-17]. Bibcode:2001JCli...14.3433T. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<3433:EOMAAO>2.0.CO;2. (原始内容存档于2022-10-28).

- ^ Cooley, S., D. Schoeman, L. Bopp, P. Boyd, S. Donner, D.Y. Ghebrehiwet, S.-I. Ito, W. Kiessling, P. Martinetto, E. Ojea, M.-F. Racault, B. Rost, and M. Skern-Mauritzen, 2022: Chapter 3: Oceans and Coastal Ecosystems and Their Services (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 379–550, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.005.

- ^ Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate — Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. [2023-08-20]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-04).

- ^ Knauth, L. Paul. Temperature and salinity history of the Precambrian ocean: implications for the course of microbial evolution. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 2005, 219 (1–2): 53–69. Bibcode:2005PPP...219...53K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.014.

- ^ Shields, Graham A.; Kasting, James F. A palaeotemperature curve for the Precambrian oceans based on silicon isotopes in cherts. Nature. 2006, 443 (7114): 969–972. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..969R. PMID 17066030. S2CID 4417157. doi:10.1038/nature05239.

- ^ Gaucher, EA; Govindarajan, S; Ganesh, OK. Palaeotemperature trend for Precambrian life inferred from resurrected proteins. Nature. 2008, 451 (7179): 704–707. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..704G. PMID 18256669. S2CID 4311053. doi:10.1038/nature06510.

- ^ Risso, VA; Gavira, JA; Mejia-Carmona, DF. Hyperstability and substrate promiscuity in laboratory resurrections of Precambrian b-lactamases. J Am Chem Soc. 2013, 135 (8): 2899–2902. PMID 23394108. doi:10.1021/ja311630a. hdl:11336/22624

.

.

- ^ Wotte, Thomas; Skovsted, Christian B.; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Kouchinsky, Artem. Isotopic evidence for temperate oceans during the Cambrian Explosion. Scientific Reports. 2019, 9 (1): 6330. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.6330W. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6474879

. PMID 31004083. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42719-4

. PMID 31004083. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42719-4  (英语).

(英语).

- ^ Wotte, Thomas; Skovsted, Christian B.; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Kouchinsky, Artem. Isotopic evidence for temperate oceans during the Cambrian Explosion. Scientific Reports. 2019, 9 (1): 6330. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.6330W. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6474879

. PMID 31004083. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42719-4 (英语).

. PMID 31004083. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42719-4 (英语).

- ^ Renne, Paul R.; Deino, Alan L.; Hilgen, Frederik J.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mark, Darren F.; Mitchell, William S.; Morgan, Leah E.; Mundil, Roland; Smit, Jan. Time Scales of Critical Events Around the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary. Science. 2013-02-07, 339 (6120): 684–687. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..684R. PMID 23393261. S2CID 6112274. doi:10.1126/science.1230492.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.