関節肢

関節肢(かんせつし[1]、arthropodized appendage[2], jointed appendage[1], arthropodium, 複数形: arthropodia[3])とは、昆虫・甲殻類・ムカデ・クモなどの節足動物に特有する、外骨格と関節に構成される付属肢である。脚・触角・顎・鰓など、多種多様な器官として現れる[4]。

「節足動物」の名の由来となっているため、時に関節肢を節足(せっそく)という場合もあるが、生物学的用語ではない。

形態

[編集]

a: 触角、lr/赤: 上唇、lb/青: 下唇、md/緑: 大顎、mx/黄: 小顎

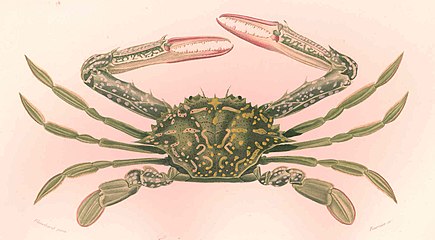

節足動物の体節ごとに並んでいる付属肢は関節肢といい、基本的には関節のある円柱形で先が細くなった構造をもつ。しかし関節肢は節足動物の生活に直結する部分で、環境や生態への適応に応じて形態が非常に変異が多く、複数の体節でできた合体節と共に分化が進んでいる。これは種類や部位により一般的な移動用の脚から、把握用の鋏と鎌・感覚用の触角・摂食用の顎(大顎、小顎)、顎基と鋏角・呼吸用の鰓・繁殖用の生殖肢まで多岐している(関節肢#関節肢の種類を参照)[4][1]。

関節肢の構成単位は、クチクラ性で硬質の外骨格によって包まれる肢節(podomere[5][1])である。各肢節の関節では、先端側の切り口の内側に次の肢節の基部が入っていて、その境目は原則として柔軟な節間膜(arthrodial membrane[6])に分かれる同時に、どこかで両肢節の支点である頑丈な関節丘(condyle)に繋がれている[7][8][9][10]。各肢節はこのような関節を介して繋がりながら、分解せずに屈折させることができる[9]。通常、肢節は付け根に1対の内骨格があり、これは直前の肢節もしくは体節内に差し込んで、内部の腱(internal tendon, 内突起 apodeme とも[11])として該当肢節の動きを操る筋肉に繋がっている[12]。なお、関節が完全なリング状の節間膜に分かれている(関節丘をもたない)、もしくは関節が癒合して不動な境目になった例もある[7]。

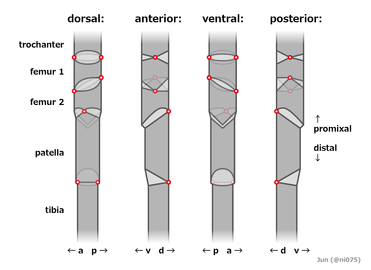

各関節の関節丘の構造は、1対でできている双関節丘(dicondylous)と、1つのみでできている単関節丘(monocondylous)という2種類がある。双関節丘の場合、この一対の関節丘を1つの軸にして、ピボット(pivot joint)もしくは蝶番(ヒンジ)のように一つの平面上で安定に関節を折り曲げる運動が可能である。言い換えれば、この関節は、一つの平面上でしか動かない[7][8][13][9][14]。それに対して単関節丘の関節は、ボールジョイントのように一定の三次元な運動方向に対応できる[7][15]。関節肢は種類によって双関節丘のみ(十脚類の脚[14]、多くの昆虫の大顎[16]など)、単関節丘のみ(イシノミの大顎[16]など)、もしくは単関節丘と双関節丘をあわせもつ(クモガタ類の脚[7][13][15]など)。関節肢は所々に肢節の長さ、関節の運動方向や可動域が異なっていて、全体でさまざまな方向に動けるようになっているのが普通である。特に基部が短縮した複数の肢節をもつことが一般的で、これにより関節肢の大部分を大幅に動かせる[7][8][17][18][19][20][21]。

甲殻類、特に鰓脚類には鰓脚状(phyllopodous)という、数少ない柔軟な肢節でできた関節肢の形態が見られ、葉状脚(phyllopod, phyllopodium)とも呼ぶ[22]。それに対して典型的な柱状肢節に分かれた関節肢の形態は「stenopodous」といい[23][24][25][26]、棒状脚(stenopod, stenopodium)とも呼ぶ[22]。

単枝型と二叉型

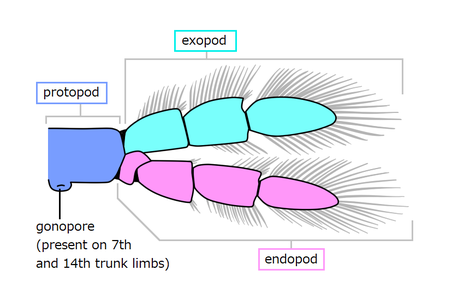

[編集]六脚類、鋏角類や多足類のほとんどの節足動物は、関節肢に分岐した肢節はなく、これは単枝型付属肢(単肢型付属肢 uniramous appendage)と呼んでいる。一方、多くの甲殻類の関節肢は、第1触角以外では基本として途中から2つに枝分かれ、二叉型付属肢(二肢型付属肢 biramous appendage)と呼ばれる。この場合、外側の分岐は外肢(枝肢[1]、exopod, exopodite)、内側の分岐は内肢(主肢[1]、endopod, endopodite, telopodite)、分岐より前の残り全ての肢節は原節(protopod, protopodite、または basipod, pasipodite)として区別される[27][28][29][30][31]。しかし甲殻類の中でも、内肢と外肢のうちどちらの一方(主に内肢)だけが発達して、外見上は単枝型に見える例が多く、十脚類(カニ・エビなど)や等脚類(ダンゴムシ・ワラジムシなど)の胸脚がその代表例である[32]。

外肢と内肢の他にも、次の2種類の構造体を関節肢の外側と内側にもつ場合がある。

外葉

[編集]外葉(exite)とは、関節肢基部の外側から突出した構造体である。甲殻類で一般に見られ、副肢(epipod, epipodite)と呼ばれる[28][33]。分類群によっては前述の外肢に似る場合もあるが、解剖学と発生学的に外肢とは別器官である。外肢は原則として肢節的で(途中に筋肉と関節がある)、単枝型付属肢の軸の分裂に由来するのに対して、外葉は途中に関節や筋肉をもたず、既存の肢節の側面から二次的に芽生えた構造体である[34][31]。

外葉は主に鰓として機能する部分で、通常は小さな葉状(鰭状、袋状、へら状)で目立たない[33]。しかし十脚類の場合、胸肢のほとんどの外葉は長大な羽毛状に発達し、鰓室に格納される[33]。

内葉

[編集]内葉(endite, または内突起)とは、関節肢の内側から突出した構造体である。多くの場合は摂食器として用いられ、この場合は顎基(gnathobase, gnathobasic endite)とも呼ばれる[35][30]。大顎類の顎(大顎と小顎)・カブトガニ類の脚・鰓脚類の胸肢などで見られる[28][34][36]。

化石群の二叉型付属肢

[編集]-

エメラルデラ(Artiopoda類)の脚

三葉虫などの Artiopoda類やメガケイラ類を始めとして、古生代、特にカンブリア紀に特有の絶滅群の関節肢は、多くが関節肢の基部外側に発達した鰭状から羽毛状の分岐を有し、これは外肢と外葉のいずれかに該当すると考えられる。もしこれは外葉であれば、これらの一見して二叉型の関節肢は、実際には外葉が発達した単枝型付属肢となる。しかしこれらの分岐は時おり途中が(外葉に存在しない)関節に分かれ、後に同じ関節肢からもそれとは別の確定的な外葉が発見されたため、外肢説(二叉型説)の方が有力で広く認められる[30][37][31]。

起源と進化

[編集]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 汎節足動物の内部系統関係と関節肢の進化[38][10] †: 絶滅群 A: 葉足の起源 B: lanceolate blade の起源 C: 関節肢の起源(葉足が原節と内肢に、lanceolate blade が外葉に変化) D: 全ての付属肢の関節肢化 E: 肢節数の減少(8節以下)と特化 |

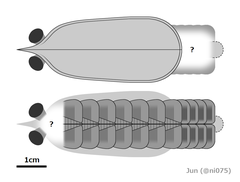

節足動物の関節肢、特に原節と内肢の部分は、同じく汎節足動物で、その共通祖先を含んだ葉足動物に見られるような、柔軟で数多くの環形の筋に分かれた葉足(lobopod)から進化したものだと考えられる[38][2][3][39][10]。このように関節肢でない付属肢が関節肢に進化する過程は「arthropodization」と呼ばれる[40][41][42][2]。フーシェンフイア類に見られるような、数多くの同形な肢節に分かれた関節肢は、各肢節の特化が進み(例えば基部の肢節は明らかに短く、途中の肢節は往々にして長い)、基本として8節以下の肢節をもつ派生的な節足動物の関節肢と葉足の中間形態を表したものだと思われる[30][2]。葉足と関節肢の相同性と進化関係は、上述のような古生物学的証拠のみならず、節足動物と同じく葉足動物から派生したと思われ、その祖先形質を色濃く受け継いだ有爪動物(カギムシ)の葉足と節足動物の関節肢の遺伝子発現からも支持を得られている[2]。

この進化は汎節足動物内で複数回に起きて、すなわち節足動物は多系統群で、関節肢は複数起源をもつという説もあった[42]が、21世紀以降では多方面の進展により、関節肢は汎節足動物のうち、単系統群の節足動物で1回のみ起源する説の方が広く認められるようになった[2][注釈 1][43][44]。また、真節足動物は全ての付属肢が関節肢であるのに対して、基盤的な節足動物とされるラディオドンタ類のれっきとした関節肢は、先頭1対の付属肢(前部付属肢)のみである[38]。これに基づいて、初期の節足動物はまず先頭の付属肢のみ関節肢に進化し、真節足動物に至る共通祖先から、関節肢の発生に関与する遺伝子をそれ以降の付属肢にも反映させ、全ての付属肢を関節肢になったと考えられる[2][10]。

関節肢の中で、元々単一の肢節が途中から関節ができて、二次的に複数の肢節に細分化した場合もある。昆虫などに見られる、複数の跗小節に分かれた跗節がその一例である[2]。このような二次的な関節は、直結する筋肉や腱をもたないことで元から存在する真の関節から区別できる[45]。

外肢の起源と進化

[編集]

節足動物の先節(上唇など)と第1体節(第1触角・鋏角・大付属肢など)以外の関節肢は、複数の分類群で単枝型と二叉型のいずれにもなり得るため、それぞれの外肢の相同性と起源に複数の解釈を与えられた。通説では、これらの関節肢は二叉型の方が節足動物の祖先形質で、単枝型は進化の過程で外肢が退化し、内肢の部分のみを残ったものと見なされる[46]。一方、遺伝子発現(甲殻類の二叉型付属肢は単枝型付属肢の軸の分裂による)と外肢の付け根の違い(鋏角類は知られる肢節より前、三葉虫は原節と体壁の間、甲殻類は原節のみ)を基に、原節と内肢のみからなる単枝型の方が節足動物の祖先形質で、各分類群の外肢は二次的でお互いに別起源とも考えられる[47][34][31]。

外葉の起源と進化

[編集]外葉は甲殻類のみ顕著に見られるため、かつては甲殻類に特有の派生形質とも考えられてきた。しかし21世紀以降では、古生物学(明らかに甲殻類でない絶滅群から外葉が発見される[31])と遺伝子発現(甲殻類以外の現生群も外葉と同じ遺伝子に抑制される部分をもつ[48])の両方面の進展により、外葉の起源はそれ以上に古く、節足動物の起源まで遡る祖先形質という説の方が有力視されつつある[49][31]。

最初の外葉は、ラディオドンタ類やオパビニア類などの基盤的な節足動物に見られるような、背面の櫛状の鰓(setal blade)の構成単位(lanceolate blade)から腹面の原節まで遊離したものだと考えられる[50][49][31]。この見解を踏まえると、基盤的な節足動物に似た鰭と単調な内肢を兼ね備えたエーラトゥスの胴肢は、その中間形態を表したかもしれない[51]。

甲殻類以外の現生節足動物(鋏角類・多足類・六脚類)は一見して外葉をもたないが、形態学と遺伝子発現の類似を基に、昆虫の翅・鋏角類の書鰓と書肺・カブトガニ類の櫂状器などが外葉から特化した部分とも解釈される[52][53][48]。しかしこれらの構造と外葉の相同性については未だに賛否両論である[53][54][55]。

関節肢の種類

[編集]

節足動物の関節肢は、形態・機能・由来・分類群によって様々な呼称やカテゴリーで区別されており、次に例挙される。関節肢としての本質がかつて疑問視され、後に広く認められるようになった構造(例:上唇、フーシェンフイア類のSPA[38])も併記する。なお、関節肢の局部のみを指す呼称(例:書鰓、顎基、鋏)、もしくは関節肢としての本質が未だに議論的/否定的な構造(例:甲殻類の擬顎[56]と尾叉[57]、イモムシとハバチの幼虫の腹脚[58][59][60])はここに含まれない。

- 脚(leg)- 節足動物全般を通じて広く見られる。有無と由来は分類群によって様々。

- 触角(antenna)- 大顎類、三葉虫などを通じて広く見られる。第1体節(甲殻類の場合は第1-2体節)由来で[38]、主に感覚に用いられる。

- 生殖肢(gonopod, genital appendage[53])- 有無と由来は分類群によって様々。繁殖行動に用いられる[61]。

- 尾毛/尾角/尾葉(cercus)- 一部の節足動物(主に六脚類)の体の末端に見られる1対の関節肢。由来は分類群によって様々。主に気流の感覚に用いられる[62][63]が、交尾や攻撃・防御のためにも用いられる[64][65]。

- 上唇(labrum)- 節足動物全般を通じて広く見られる。先節由来で[38]、摂食に用いられる。

- 鋏角(chelicera)- 第1体節由来で[53][38]、主に摂食に用いられる[53]。

- 触肢(pedipalp/palp)- 第2体節由来で、分類群によって歩行・感覚・摂食・交接などに用いられる[53]。

- 蓋板/鰓蓋(operculum)- 真鋏角類に特有。後体第2-7節(第8-13体節)由来で、主に呼吸器(書鰓と書肺)を支えるのに用いられる[53]。

- 生殖口蓋(genital operculum)- 真鋏角類の後体第2節(第8体節)の蓋板。生殖口を覆うのに用いられる[53]。

- 担卵肢(oviger)- ウミグモ類に特有。第3体節由来で、育児や体の手入れに用いられる[53]。

- 唇様肢(chilarium)- カブトガニ類に特有。第7体節由来で、摂食に用いられる[53]。

- 下層板(Metastoma)- ウミサソリ類・カスマタスピス類などに特有。第7体節由来で、摂食用とされる[53]。

- 櫛状板/ペクチン(pectine)- サソリ類に特有。第9体節由来で、感覚に用いられる[53]。

- 顎肢(forcipule[69])- 第1胴節(第6体節)由来で[66]、摂食に用いられる[70]。

- 曳航肢(ultimate leg[69])- 特化した最終1対の歩脚。分類群によって感覚・自衛・求愛・バランス調節などに用いられる[71]。

- 第2触角(second antenna, antenna)- 第2体節由来の触角。分類群や成長段階によって感覚や遊泳などに用いられる。

- 胸肢(thoracopod)- 甲殻類の胸部(第6体節以降)の関節肢。機能は分類群や部位によって様々[72][73]。

- 腹肢(pleopod)- 軟甲類に特有[57]。腹部(第14-19体節)由来で、分類群によって遊泳や呼吸などに用いられる[79]。

- 叉状器/跳躍器[81](furcula)- トビムシ類に特有。第4腹節(第12体節)由来で、跳躍に用いられる[82]。

- 腹刺 (abdominal stylus) - イシノミ類・コムシ類・カマアシムシ類に見られる。腹部(第9体節以降)由来の痕跡的な関節肢[83]。

- エデアグス(aedeagus/aedoeagus/edeagus)- 昆虫の雄に特有。第9-10腹節(第17-18体節)由来の生殖肢[84]。

鋏角類・大顎類以外の化石群に特有

[編集]

- 大付属肢(great appendage, short-great appendage/SGA)- メガケイラ類に特有。第1体節に由来で[38]、摂食用とされる[85]。

- 前部付属肢(frontal appendage)- ラディオドンタ類の最初の関節肢。通説では先節由来とされ[86][38]、摂食用とされる[87] 。なおこの名称はラディオドンタ類に限らず、オパビニア類、パンブデルリオン、ケリグマケラやシベリオン類など、他の基盤的な節足動物における関節肢でない先頭の付属肢まで幅広く用いられる[38] 。

- Specialized post-antennal appendage/SPA - フーシェンフイア類に特有。通説では第2体節由来とされ[88][38]、摂食用とされる[89]。

形態と機能による区分

[編集]- 歩脚状(pediform、甲殻類の場合は一般に stenopodous, 柱状脚 stenopod とも[23][24][25])- 歩脚など[90][53](この類の関節肢は必ずしも脚/歩脚とは限らない)。

- 鋏状/ハサミ状(chelate、cheliform[91])- 2節の肢節由来の可動指と不動指でできた構造。十脚類の鋏脚、四肺類以外の鋏角類の鋏角など[53]。

- 亜鋏状/亜ハサミ状/鎌状(subchelate[92])- クモの鋏角、カマキリの前脚、シャコ類の顎脚など。

- multichelate - 3節以上の肢節由来の指でできた"多重鋏"構造。メガケイラ類の大付属肢、サソリモドキの触肢[29]。

- raptorial - 獲物を掴む用の関節肢全般。カマキリの前脚、シャコ類の捕脚(第2顎脚)、ウデムシの触肢など[53]。

- 顎状(gnathal[73])- 大顎類の大顎や小顎など。

- 顎基状(gnathobasic)- 顎基をもつ関節肢全般。カブトガニ類の脚など[30]。

- 鰓脚状(phyllopodous, 葉状脚 phyllopod)- 十脚類の小顎、鰓脚類の胸肢など[25][26]。

- 触角状(antenniform)- 大顎類などの触角、ウデムシの第1脚など[53](この類の関節肢は必ずしも触角とは限らない)。

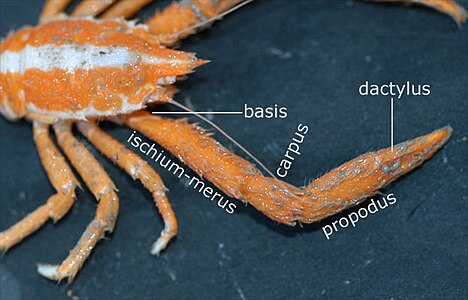

肢節の名称と数

[編集]関節肢は基部から内肢の先端にかけて、各肢節が異なる名称で区別される。その中で、甲殻類の場合はヒトの上肢骨、鋏角類・多足類・六脚類の場合は下肢骨に使われる名称で呼ばれている。採用した体系は大まかなに次の通り分類群と関節肢の種類により異なるが、同じ関節肢が文献記載により体系が異なる場合がある・肢節の番目と名称は必ずしも相同性を反映するとは限らない・同じ肢節名が文献記載により異なる肢節を指す場合があるなど、混同の注意が必要である[7][93][94][48]。

- 「基節」に対応する英語と「coxa」に対応する日本語は、通常では甲殻類(coxa=底節、basis=基節)と他の節足動物(coxa=基節)で異なり[95]、甲殻類では日本語の対応関係が逆(coxa=基節、basis=底節)になったこともある[96][97]。

- 「前跗節(pretarsus)」は通常では跗節(tarsus)の先端側に続く肢節(apotele)を指している[7][98][99][100]が、鋏角類の蹠節/基跗節(basitarsus)[101]・六脚類の跗節における最終跗小節(distitarsus)[102]のいずれかを指すのに用いられる場合もある。

- 「端跗節」は昆虫の跗節における最終跗小節[102]・鋏角類の蹠節/基跗節以降の"跗節"(telotarsus)[103]を指すのに用いられる。

- 「metatarsus」は鋏角類の蹠節/基跗節[7][94]・六脚類の跗節における第1跗小節[100]を指すのに用いられる。

肢節の番目 分類群

|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 六脚類の脚[100][注釈 2][104][48] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][48]) | ||||

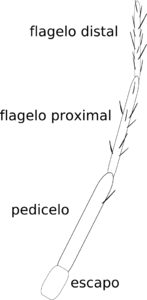

| 六脚類:昆虫の触角[105][106] | 柄節 scape | 梗節 pedicel | 鞭節 flagellum[注釈 5] | |||||||

| 甲殻類:軟甲類の脚(前底節あり体系)[28][48] | 前底節 precoxa | 底節 coxa | 基節 basis | 座節 ischium | 長節 merus | 腕節 carpus | 前節 propodus | 指節 dactylus | ||

| 甲殻類:軟甲類の脚(前底節なし体系)[34] | 底節 coxa | 基節 basis | 座節 ischium | 長節 merus | 腕節 carpus | 前節 propodus | 指節 dactylus | |||

| 多足類:ムカデ(ゲジ)の顎肢[69] | 基節 coxa | trochanteroprefemur[注釈 6] | 腿節 femur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus | ungulum | ||||

| 多足類:ムカデ(ゲジ以外)の顎肢[69][注釈 7][107] | trochanteroprefemur | 腿節 femur | 脛節 tibia | tarsungulum[注釈 8] | ||||||

| 多足類:ムカデの脚(腿節2節体系)[69] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 前腿節 prefemur | 腿節 femur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][108][109]) | |||

| 多足類:ムカデとヤスデの脚(転節2節体系)[108][109] | 基節 coxa | 第1転節 trochanter 1 | 第2転節 trochanter 2 | 腿節 femur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][108][109]) | |||

| 多足類:ヤスデの脚(腿節3節体系)[110] | 基節 coxa | 前腿節 prefemur | 腿節 femur | 後腿節 postfemur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][109]) | |||

| 多足類:コムカデとエダヒゲムシの脚[111][112] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][108] | ||||

| 鋏角類:ウミグモの脚(転節・膝節なし、脛節2節体系)[113] | 第1基節 coxa 1 | 第2基節 coxa 2 | 第3基節 coxa 3 | 腿節 femur | 第1脛節 tibia 1 | 第2脛節 tibia 2 | 跗節 tarsus | 趾節 propodus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:ウミグモの脚(転節・膝節あり、転節2節体系)[114] | 基節 coxa | 第1転節 trochanter 1 | 第2転節 trochanter 2 | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | (跗節 tarsus の一部扱い) | (跗節 tarsus の一部扱い) | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:ウミグモの脚(転節・膝節あり、腿節2節体系)[7] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / postfemur / telofemur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | (跗節 tarsus の一部扱い) | (跗節 tarsus の一部扱い) | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:カブトガニ類の第1-4脚[115][101] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | tibiotarsus[注釈 9][7] | pretarsus / apotele / dactylopodite | ||||

| 鋏角類:カブトガニ類の第5脚[115][101] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus / pretarsus | 前跗節 pretarsus / apotele | |||

| 鋏角類:クモガタ類の触肢[94] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |||

| 鋏角類:クモガタ類の脚 | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus / pretarsus[注釈 10] | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | ||

| 鋏角類:胸板ダニ類の脚[7][118] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur[注釈 11] | 膝節 patella / genu | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus[注釈 12] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |||

| 鋏角類:マダニの脚(転節2節体系)[94] | 基節 coxa | 第1転節 trochanter 1 | 第2転節 trochanter 2 | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella / genu | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus[注釈 13] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | ||

| 鋏角類:マダニの脚("第2転節"=腿節の一部体系)[7] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella / genu | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus[注釈 13] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |||

| 鋏角類:アシナガダニの第1脚[119] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 膝節 patella / genu | basitibia | telotibia | 基跗節 basitarsus | 端跗節 telotarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) |

| 鋏角類:アシナガダニの第3-4脚[119] | 基節 coxa | 第1転節 trochanter 1 | 第2転節 trochanter 2 | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella / genu | 脛節 tibia | 基跗節 basitarsus | 端跗節 telotarsus | acrotarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) |

| 鋏角類:クツコムシの第3-4脚(転節2節体系)[120] | 基節 coxa | 第1転節 trochanter 1 | 第2転節 trochanter 2 | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 13] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:クツコムシの第3-4脚(腿節2節体系)[7] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 13] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:ヒヨケムシの第1-2脚(膝節なし体系)[115] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | ||

| 鋏角類:ヒヨケムシの第1-2脚(膝節あり体系)[7] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | ||

| 鋏角類:ヒヨケムシの第3-4脚(膝節なし体系)[115] | 基節 coxa | 第1転節 trochanter 1 | 第2転節 trochanter 2 | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:ヒヨケムシの第3-4脚(膝節あり体系)[7][121] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus[注釈 3] | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |

| 鋏角類:カニムシ Cheliferoidea上科の脚と Chthonioidea上科の第1-2脚[122](膝節なし体系)[115] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |||

| 鋏角類:カニムシ Cheliferoidea上科の脚と Chthonioidea上科の第1-2脚[122](膝節あり体系)[7][123] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 跗節 tarsus / telotarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | |||

| 鋏角類:カニムシCheliferoidea上科以外の第3-4脚[122](膝節なし体系)[115] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur | 第2腿節 femur 2 / 後腿節 postfemur / telofemur | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) | ||

| 鋏角類:カニムシCheliferoidea上科以外の第3-4脚[122](膝節あり体系)[7][123] | 基節 coxa | 転節 trochanter | 腿節 femur | 膝節 patella | 脛節 tibia | 蹠節 metatarsus / 基跗節 basitarsus | 跗節 tarsus / 端跗節 telotarsus | (前跗節 pretarsus / apotele[注釈 4][7]) |

脚注

[編集]注釈

[編集]- ^ 葉足動物のディアニアは一時的に関節肢をもつと解釈され、これは節足動物のものとは別起源ともされていたが、再検証により葉足の見間違いだと判明した。詳細はディアニア#復元史と系統関係および次の脚注を参照。

- ^ 基節 coxa より前の側板 pleuron/pleurite は肢節由来とされ、一部は亜基節 subcoxa とも呼ぶ。

- ^ a b c d e f g h 種類により複数の跗小節 tarsomeres に細分される場合がある。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y クモガタ類・ウミグモ類・多足類・六脚類などの目立たない前跗節 pretarsus/apotele は通常では肢節扱いされていないが、解剖学上では真の最終肢節である。

- ^ 一般に複数の鞭節節 Flagellomere に細分される。

- ^ 転節 trochanter と 前腿節 prefemur の癒合でできた複合体。

- ^ 元の第1肢節である基節 coxa は腹板と癒合し、基胸板 coxosternite の一部となっている。

- ^ 跗節 tarsus と ungulum の癒合でできた複合体。

- ^ 脛節 tibia と跗節 tarsus の癒合でできた複合体とされる。

- ^ 鋏角類の同じ脚における蹠節 metatarsus と跗節 tarsus は通常では2肢節扱いされるが、解剖学上では全体的に触肢跗節に連続相同で、2節(basitarsus, telotarsus)に分化した1肢節(跗節 tarsus)である。

- ^ 腿節が種類により2節(第1腿節 femur 1 / 前腿節 prefemur / basifemur + 第2腿節 femur 2 / postfemur / telofemur)に細分される場合がある。

- ^ 跗節が種類により2節(basitarsus + telotarsus)もしくは3節(basitarsus + telotarsus + acrotarsus)に細分される場合がある。

- ^ a b c d 複数の跗小節 tarsomeres に細分される。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c d e f 第2版, 世界大百科事典. “関節肢とは”. コトバンク. 2022年4月12日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jockusch, Elizabeth L. (2017-09-01). “Developmental and Evolutionary Perspectives on the Origin and Diversification of Arthropod Appendages” (英語). Integrative and Comparative Biology 57 (3): 533–545. doi:10.1093/icb/icx063. ISSN 1540-7063.

- ^ a b Oliveira, Ivo de Sena; Kumerics, Andreas; Jahn, Henry; Müller, Mark; Pfeiffer, Franz; Mayer, Georg (2019-10-16). “Functional morphology of a lobopod: case study of an onychophoran leg”. Royal Society Open Science 6 (10): 191200. doi:10.1098/rsos.191200. PMC 6837196. PMID 31824728.

- ^ a b Fusco, Giuseppe; Minelli, Alessandro (2013), Minelli, Alessandro; Boxshall, Geoffrey, eds. (英語), Arthropod Segmentation and Tagmosis, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 197–221, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36160-9_9, ISBN 978-3-642-36159-3 2022年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ “podomereの意味・使い方 - 英和辞典 WEBLIO辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2020年2月3日閲覧。

- ^ “arthrodial membraneの意味・使い方 - 英和辞典 WEBLIO辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2020年2月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am SHULTZ, JEFFREY W. (1989-09-01). “Morphology of locomotor appendages in Arachnida: evolutionary trends and phylogenetic implications”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 97 (1): 1–56. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1989.tb00552.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b c Wootton, R. (1999). “Invertebrate paraxial locomotory appendages: design, deformation and control.”. The Journal of experimental biology.

- ^ a b c Alexander, David E. (2017-01-01), Alexander, David E., ed. (英語), Chapter 5 - Systems and Scaling, Academic Press, pp. 121–150, ISBN 978-0-12-804404-9 2022年4月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2020-11-02). “Arthropod Origins: Integrating Paleontological and Molecular Evidence”. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-124437. ISSN 1543-592X.

- ^ “apodemeの意味・使い方・読み方 | Weblio英和辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2022年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ Bitsch, Colette; Bitsch, Jacques (2002-02-01). “The endoskeletal structures in arthropods: cytology, morphology and evolution” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 30 (3): 159–177. doi:10.1016/S1467-8039(01)00032-9. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b Murillo, Wilder Ferney Zapata (2011). “Biology of Spiders” (英語). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973482-5.

- ^ a b Cattaert, Daniel (2019年4月10日). “Control of Locomotion in Crustaceans” (英語). The Oxford Handbook of Invertebrate Neurobiology. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190456757.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190456757-e-23. 2020年12月22日閲覧。

- ^ a b Garwood, Russell; Dunlop, Jason (2014-07). “The walking dead: Blender as a tool for paleontologists with a case study on extinct arachnids” (英語). Journal of Paleontology 88 (4): 735–746. doi:10.1666/13-088. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ a b Blanke, Alexander (2019). Krenn, Harald W.. ed (英語). Insect Mouthparts: Form, Function, Development and Performance. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 175–202. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-29654-4_6. ISBN 978-3-030-29654-4

- ^ Gasparetto, Alessandro; Vidoni, Renato; Seidl, Tobias (2008-09). “Kinematic study of the spider system in a biomimetic perspective”. 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems: 3077–3082. doi:10.1109/IROS.2008.4650677.

- ^ Frantsevich, Leonid; Wang, Weiying (2009-01-01). “Gimbals in the insect leg” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 38 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2008.06.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Reußenzehn, Stefan (2010). “Mechanical design of the legs of Dolomedes aquaticus - Novel approaches to quantify the hydraulic contribution to joint movement and to create a segmented 3D spider model” (英語). undefined.

- ^ Turetzek, Natascha; Pechmann, Matthias; Schomburg, Christoph; Schneider, Julia; Prpic, Nikola-Michael (2016-01). “Neofunctionalization of a Duplicate dachshund Gene Underlies the Evolution of a Novel Leg Segment in Arachnids” (英語). Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (1): 109–121. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv200. ISSN 0737-4038.

- ^ SCHMIDT, Michel; MELZER, Roland R.; BICKNELL, Russell D. C. (2021-10-10). “Kinematics of whip spider pedipalps: a 3D comparative morpho‐functional approach”. Integrative Zoology 17 (1): 156–167. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12591. ISSN 1749-4877.

- ^ a b 季雄, 椎野 (1963). “甲殻類系統発生雑記(動物分類学会シンポジウム講演要旨)”. 動物分類学会会報 28: 7–12. doi:10.19004/jsszc.28.0_7.

- ^ a b “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (Stenopodous)”. research.nhm.org. 2022年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b Thorp, James H.; Rogers, D. Christopher; Covich, Alan P. (2015-01-01), Thorp, James H.; Rogers, D. Christopher, eds. (英語), Chapter 27 - Introduction to “Crustacea”, Academic Press, pp. 671–686, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-385026-3.00027-9, ISBN 978-0-12-385026-3 2022年4月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Olesen, J.; Richter, S.; Scholtz, G. (2001-12). “The evolutionary transformation of phyllopodous to stenopodous limbs in the Branchiopoda (Crustacea)--is there a common mechanism for early limb development in arthropods?”. The International Journal of Developmental Biology 45 (8): 869–876. ISSN 0214-6282. PMID 11804030.

- ^ a b Pabst, Tino; Scholtz, Gerhard (2009-01-01). “The Development of Phyllopodous Limbs in Leptostraca and Branchiopoda” (英語). Journal of Crustacean Biology 29 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1651/08/3034.1. ISSN 0278-0372.

- ^ “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (protopod)”. research.nhm.org. 2021年12月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Cohen, A. C.; Martin, Joel W.; Kornicker, L. S. (2007). Homology of Holocene Ostracode Biramous Appendages with those of Other Crustaceans: The Protopod, Epipod, Exopod and Endopod. doi:10.1111/J.1502-3931.1998.TB00514.X.

- ^ a b Haug, Joachim T; Briggs, Derek EG; Haug, Carolin (2012). “Morphology and function in the Cambrian Burgess Shale megacheiran arthropod Leanchoilia superlata and the application of a descriptive matrix” (英語). BMC Evolutionary Biology 12 (1): 162. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-162. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3468406. PMID 22935076.

- ^ a b c d e Yang, Jie; Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Legg, David A.; Lan, Tian; Hou, Jin-bo; Zhang, Xi-guang (2018-02-01). “Early Cambrian fuxianhuiids from China reveal origin of the gnathobasic protopodite in euarthropods” (英語). Nature Communications 9 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02754-z. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ a b c d e f g Liu, Yu; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Schmidt, Michel; Bond, Andrew D.; Melzer, Roland R.; Zhai, Dayou; Mai, Huijuan; Zhang, Maoyin et al. (2021-07-30). “Exites in Cambrian arthropods and homology of arthropod limb branches” (英語). Nature Communications 12 (1): 4619. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24918-8. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ “A TEXTBOOK OF ARTHROPOD ANATOMY”. flexpub.com. 2022年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Maas, Andreas; Haug, Carolin; Haug, Joachim; Olesen, Jørgen; Zhang, Xi-Guang; Waloszek, Dieter (2009-09-01). “[1]”. Arthropod Systematics and Phylogeny 67: 255–273.

- ^ a b c d Wolff, Carsten; Scholtz, Gerhard (2008-05-07). “The clonal composition of biramous and uniramous arthropod limbs” (英語). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275 (1638): 1023–1028. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1327. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2600901. PMID 18252674.

- ^ “gnathobase”. Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. 2021年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ Bicknell, Russell D. C.; Ledogar, Justin A.; Wroe, Stephen; Gutzler, Benjamin C.; Watson, Winsor H.; Paterson, John R. (2018-10-24). “Computational biomechanical analyses demonstrate similar shell-crushing abilities in modern and ancient arthropods”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285 (1889): 20181935. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1935. PMC 6234888. PMID 30355715.

- ^ Hou, Jin-bo; Hughes, Nigel C.; Hopkins, Melanie J. (2021-03-31). “The trilobite upper limb branch is a well-developed gill”. Science Advances 7 (14): eabe7377. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe7377.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Janssen, Ralf; Budd, Graham E. (2017-05-01). “Origin and evolution of the panarthropod head – A palaeobiological and developmental perspective” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 354–379. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.011. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2019-06-17). “The Phylogeny and Evolutionary History of Arthropods” (English). Current Biology 29 (12): R592–R602. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.057. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 31211983.

- ^ “arthropodizationの意味・使い方・読み方 | Weblio英和辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2022年4月12日閲覧。

- ^ Grasshoff, M. (1981-10-31). “Arthropodization as a bio mechanical process and the origin of trilobite construction” (英語). Palaeontologische Zeitschrift 55 (3-4): 219–236.

- ^ a b Min, G. S.; Kim, S. H.; Kim, W. (1998-02-28). “Molecular phylogeny of arthropods and their relatives: polyphyletic origin of arthropodization”. Molecules and Cells 8 (1): 75–83. ISSN 1016-8478. PMID 9571635.

- ^ Ma, Xiaoya; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Legg, David A.; Hou, Xianguang (2013-05-). “The morphology and phylogenetic position of the Cambrian lobopodian Diania cactiformis”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 12 (4): 445–457. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.770418. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Ou, Qiang; Mayer, Georg (2018-09-20). “A Cambrian unarmoured lobopodian, †Lenisambulatrix humboldti gen. et sp. nov., compared with new material of †Diania cactiformis” (英語). Scientific Reports 8 (1): 13667. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-31499-y. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ Angelini, David R; Smith, Frank W; Jockusch, Elizabeth L (2012-02-01). “Extent With Modification: Leg Patterning in the Beetle Tribolium castaneum and the Evolution of Serial Homologs”. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2 (2): 235–248. doi:10.1534/g3.111.001537. ISSN 2160-1836. PMC 3284331. PMID 22384402.

- ^ Briggs, D. E. G.; Siveter, D. J.; Siveter, D. J.; Sutton, M. D.; Garwood, R. J.; Legg, D. (2012-09-25). “Silurian horseshoe crab illuminates the evolution of arthropod limbs” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (39): 15702–15705. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205875109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3465403. PMID 22967511.

- ^ Hejnol, Andreas; Scholtz, Gerhard (2004-10). “Clonal analysis of Distal-less and engrailed expression patterns during early morphogenesis of uniramous and biramous crustacean limbs”. Development Genes and Evolution 214 (10): 473–485. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0424-2. ISSN 0949-944X. PMID 15300435.

- ^ a b c d e f Bruce, Heather S.; Patel, Nipam H. (2020-12). “Knockout of crustacean leg patterning genes suggests that insect wings and body walls evolved from ancient leg segments” (英語). Nature Ecology & Evolution 4 (12): 1703–1712. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-01349-0. ISSN 2397-334X.

- ^ a b Van Roy, Peter; Daley, Allison C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2015-06). “Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps” (英語). Nature 522 (7554): 77–80. doi:10.1038/nature14256. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Budd, Graham E. (1996). “The morphology of Opabinia regalis and the reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group” (英語). Lethaia 29 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01831.x. ISSN 1502-3931.

- ^ Fu, Dongjing; Legg, David A.; Daley, Allison C.; Budd, Graham E.; Wu, Yu; Zhang, Xingliang (2022-03-28). “The evolution of biramous appendages revealed by a carapace-bearing Cambrian arthropod”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 377 (1847): 20210034. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0034.

- ^ Damen, Wim G.M.; Saridaki, Theodora; Averof, Michalis (2002-10). “Diverse Adaptations of an Ancestral Gill” (英語). Current Biology 12 (19): 1711–1716. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01126-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Dunlop, Jason A.; Lamsdell, James C. (2017). “Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 395. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Di, Zhiyong; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Sharma, Prashant P. (2018-05-21). “Homeosis in a scorpion supports a telopodal origin of pectines and components of the book lungs”. BMC Evolutionary Biology 18 (1): 73. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1188-z. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5963125. PMID 29783957.

- ^ Ohde, Takahiro; Mito, Taro; Niimi, Teruyuki (2022-02-21). “A hemimetabolous wing development suggests the wing origin from lateral tergum of a wingless ancestor” (英語). Nature Communications 13 (1): 979. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28624-x. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Wolff, Carsten; Scholtz, Gerhard (2006-12-04). “Cell lineage analysis of the mandibular segment of the amphipod Orchestia cavimana reveals that the crustacean paragnaths are sternal outgrowths and not limbs”. Frontiers in Zoology 3: 19. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-3-19. ISSN 1742-9994. PMC 1702535. PMID 17144925.

- ^ a b c Kutschera, Verena; Maas, Andreas; Waloszek, Dieter (2012). “Uropods of Eumalacostraca (Crustacea s.l.: Malacostraca) and their phylogenetic significance” (英語). Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 70 (3): 181–206. ISSN 1863-7221.

- ^ Suzuki, Y.; Palopoli, M. F. (2001-10). “Evolution of insect abdominal appendages: are prolegs homologous or convergent traits?”. Development Genes and Evolution 211 (10): 486–492. doi:10.1007/s00427-001-0182-3. ISSN 0949-944X. PMID 11702198.

- ^ Du, Xiaoliang; Yue, Chao; Hua, Baozhen (2009-08). “Embryonic development of the scorpionflyPanorpa emarginataCheng with special reference to external morphology (Mecoptera: Panorpidae)”. Journal of Morphology 270 (8): 984–995. doi:10.1002/jmor.10736. ISSN 0362-2525.

- ^ Bitsch, Jacques (2012-08). “The controversial origin of the abdominal appendage-like processes in immature insects: are they true segmental appendages or secondary outgrowths? (Arthropoda Hexapoda)”. Journal of Morphology 273 (8): 919–931. doi:10.1002/jmor.20031. ISSN 1097-4687. PMID 22549894.

- ^ “Gonopod definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary” (英語). www.collinsdictionary.com. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Cercus | anatomy” (英語). Encyclopedia Britannica. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ 楯夫, 下澤 (1996). “昆虫の気流感覚器”. Bme 10 (11): 29–37. doi:10.11239/jsmbe1987.10.11_29.

- ^ “大阪市立自然史博物館 質問コーナー”. www3.mus-nh.city.osaka.jp. 2023年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ Tiegs, O. W. (1945-03-01). “The Post-embryonic Development of Hanseniella agilis (Symphyla)”. Journal of Cell Science S2-85 (338): 191–328. doi:10.1242/jcs.s2-85.338.191. ISSN 0021-9533.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Cynthia L.; Kaufman, Thomas C. (2002-03-01). “Exploring the myriapod body plan: expression patterns of the ten Hox genes in a centipede” (英語). Development 129 (5): 1225–1238. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 11874918.

- ^ “gnathochilariumの意味・使い方・読み方 | Weblio英和辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ Shear, William A.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2010-03-01). “The geological record and phylogeny of the Myriapoda” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 39 (2): 174–190. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2009.11.002. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b c d e Bonato, Lucio; Edgecombe, Gregory; Lewis, John; Minelli, Alessandro; Pereira, Luis; Shelley, Rowland; Zapparoli, Marzio (2010-11-18). “A common terminology for the external anatomy of centipedes (Chilopoda)” (英語). ZooKeys 69: 17–51. doi:10.3897/zookeys.69.737. ISSN 1313-2970.

- ^ Dugon, Michel M. (2015). Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Malhotra, Anita. eds (英語). Evolution of Venomous Animals and Their Toxins. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6727-0_1-1. ISBN 978-94-007-6727-0

- ^ Kenning, Matthes; Müller, Carsten H. G.; Sombke, Andy (2017-11-14). “The ultimate legs of Chilopoda (Myriapoda): a review on their morphological disparity and functional variability” (英語). PeerJ 5: e4023. doi:10.7717/peerj.4023. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ Averof, Michalis; Patel, Nipam H. (1997-08). “Crustacean appendage evolution associated with changes in Hox gene expression” (英語). Nature 388 (6643): 682–686. doi:10.1038/41786. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b Martin, Arnaud; Serano, Julia M.; Jarvis, Erin; Bruce, Heather S.; Wang, Jennifer; Ray, Shagnik; Barker, Carryn A.; O’Connell, Liam C. et al. (2016-01-11). “CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis Reveals Versatile Roles of Hox Genes in Crustacean Limb Specification and Evolution” (English). Current Biology 26 (1): 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.021. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 26687626.

- ^ “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (Maxilliped)”. research.nhm.org. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ Haug, Joachim T.; Haug, Carolin; Maas, Andreas; Kutschera, Verena; Waloszek, Dieter (2010-09-21). “Evolution of mantis shrimps (Stomatopoda, Malacostraca) in the light of new Mesozoic fossils”. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10 (1): 290. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-290. ISSN 1471-2148.

- ^ 世界大百科事典内言及. “捕脚とは”. コトバンク. 2021年12月14日閲覧。

- ^ 世界大百科事典内言及. “咬脚とは”. コトバンク. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (Cheliped)”. research.nhm.org. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (pleopod)”. research.nhm.org. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Crustacea Glossary::Definitions (uropod)”. research.nhm.org. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “furculaの意味・使い方・読み方 | Weblio英和辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Springtail | arthropod” (英語). Encyclopedia Britannica. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Archaeognatha - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics”. www.sciencedirect.com. 2020年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ Boudinot, Brendon E. (2018-11-01). “A general theory of genital homologies for the Hexapoda (Pancrustacea) derived from skeletomuscular correspondences, with emphasis on the Endopterygota” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 47 (6): 563–613. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2018.11.001. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Haug, Joachim T.; Waloszek, Dieter; Maas, Andreas; Liu, Yu; Haug, Carolin (2012-03). “Functional morphology, ontogeny and evolution of mantis shrimp-like predators in the Cambrian: MANTIS SHRIMP-LIKE CAMBRIAN PREDATORS” (英語). Palaeontology 55 (2): 369–399. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01124.x.

- ^ Cong, Peiyun; Ma, Xiaoya; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. (2014-09). “Brain structure resolves the segmental affinity of anomalocaridid appendages” (英語). Nature 513 (7519): 538–542. doi:10.1038/nature13486. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Moysiuk, J.; Caron, J.-B. (2019-08-14). “A new hurdiid radiodont from the Burgess Shale evinces the exploitation of Cambrian infaunal food sources”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286 (1908): 20191079. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1079. PMC 6710600. PMID 31362637.

- ^ Ma, Xiaoya; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. (2012-10). “Complex brain and optic lobes in an early Cambrian arthropod” (英語). Nature 490 (7419): 258–261. doi:10.1038/nature11495. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Yang, Jie; Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Butterfield, Nicholas J.; Zhang, Xi-guang (2013-02). “Specialized appendages in fuxianhuiids and the head organization of early euarthropods” (英語). Nature 494 (7438): 468–471. doi:10.1038/nature11874. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ “Definition of PEDIFORM” (英語). www.merriam-webster.com. 2020年12月22日閲覧。

- ^ “chela, chelae, chelate, cheliform, cheliped”. bugguide.net. 2020年12月22日閲覧。

- ^ “subchelate” (英語). Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. 2020年12月22日閲覧。

- ^ Wolf, Harald; Harzsch, Steffen (2002-12-01). “Evolution of the arthropod neuromuscular system. 1. Arrangement of muscles and innervation in the walking legs of a scorpion: Vaejovis spinigerus (Wood, 1863) Vaejovidae, Scorpiones, Arachnida” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 31 (3): 185–202. doi:10.1016/S1467-8039(02)00043-9. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b c d e Snodgrass, R. E. (1952) (英語). V. The Arachnida. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-007. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ 邦男 岩槻, 峻輔 馬渡, 良輔 石川『節足動物の多様性と系統』裳華房、東京、2008年。ISBN 978-4-7853-5829-7。OCLC 676535371。

- ^ 内田, 亨 (1964-01-01). 動物系統分類学〈第7巻 上〉節足動物. 中山書店

- ^ 弘之, 渡辺 (1999). 青木淳一. ed. “日本産土壌動物分類のための図解検索”. 日本生態学会誌 (東海大学出版会) 49 (2): 201. doi:10.18960/seitai.49.2_201_1. ISBN 4-486-01443-X.

- ^ 大石博之、松隈明彦、相原安津夫「佐賀県武雄市の漸新統より産出したカブトガニの足跡化石」『九州大学理学部研究報告 地球惑星科学』第18巻第1号、1993年、73–84頁、ISSN 0916-7315。

- ^ Capinera, John L., ed. (2008) (英語), Pretarsus, Springer Netherlands, pp. 3046–3046, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_3123, ISBN 978-1-4020-6359-6 2022年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Snodgrass, R. E. (1952) (英語). XI. The Hexapoda. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-013. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ a b c Bicknell, Russell D. C.; Klinkhamer, Ada J.; Flavel, Richard J.; Wroe, Stephen; Paterson, John R. (2018-02-14). “A 3D anatomical atlas of appendage musculature in the chelicerate arthropod Limulus polyphemus” (英語). PLOS ONE 13 (2): e0191400. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191400. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5812571. PMID 29444161.

- ^ a b “BSI生物科学研究所 衛生昆虫のページ”. bsikagaku.jp. 2022年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ 坂寄 廣 (2014). “岡山産オウギツチカニムシ Allochthonius(Allochthonius)opticus の再記載 (カニムシ目,ツチカニムシ科)”. 茨城県自然博物館研究報告 Bull. Ibaraki Nat. Mus. 17: 1-6.

- ^ Coulcher, Joshua F.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Telford, Maximilian J. (2015-10-28). “Molecular developmental evidence for a subcoxal origin of pleurites in insects and identity of the subcoxa in the gnathal appendages” (英語). Scientific Reports 5 (1): 15757. doi:10.1038/srep15757. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4623811. PMID 26507752.

- ^ Gayubo, Severiano F. (2008), Capinera, John L., ed. (英語), Antennae of Hexapods, Springer Netherlands, pp. 159–163, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_10240, ISBN 978-1-4020-6359-6 2022年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ Minelli, A. (2017-04-21). “The insect antenna: segmentation, patterning and positional homology”. Journal of Entomological and Acarological Research 49 (1). doi:10.4081/jear.2017.6680. ISSN 2279-7084.

- ^ (英語) coxosternite, (2018-09-27) 2022年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Snodgrass, R. E. (1952) (英語). VII. The Chilopoda. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-009. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ a b c d Snodgrass, R. E. (1952) (英語). VIII. The Diplopoda. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-010. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ 第2版,日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ), 世界大百科事典. “オビヤスデとは”. コトバンク. 2022年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ Snodgrass, R. E. (1952) (英語). X. The Symphyla. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-012. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ Snodgrass, R. E. (1952) (英語). IX. The Pauropoda. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501740800-011. ISBN 978-1-5017-4080-0

- ^ Crooker, Allen (2008), Capinera, John L., ed. (英語), Sea Spiders (Pycnogonida), Springer Netherlands, pp. 3321–3335, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_4098, ISBN 978-1-4020-6359-6 2021年12月19日閲覧。

- ^ Bergström, Jan; Stürmer, Wilhelm; Winter, Gerhard (1980-06-01). “Palaeoisopus, Palaeopantopus and Palaeothea, pycnogonid arthropods from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate, West Germany.”. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 54: 7–54.

- ^ a b c d e f g van der Hammen, L. (1986-01-01). “Comparative studies in Chelicerata IV. Apatellata, Arachnida, Scorpionida, Xiphosura” (英語). Zoologische Verhandelingen 226 (1): 1–52.

- ^ SHULTZ, JEFFREY W. (1993-08-01). “Muscular anatomy of the giant whipscorpion Mastigoproctus giganteus (Lucas) (Arachnida: Uropygi) and its evolutionary significance”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 108 (4): 335–365. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1993.tb00302.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Grams, Markus; Wirkner, Christian S.; Runge, Jens (2018-03-01). “Serial and special: Comparison of podomeres and muscles in tactile vs walking legs of whip scorpions (Arachnida, Uropygi)” (英語). Zoologischer Anzeiger 273: 75–101. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2017.06.001. ISSN 0044-5231.

- ^ “Tarsus I subdivisions and apotele | idtools.org”. 2021年12月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b J. Dunlop, Carolin Sempf, J. Wunderlich (2010). A new opilioacarid mite in Baltic amber.

- ^ Seiden, Paul A. (1992/ed). “Revision of the fossil ricinuleids” (英語). Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 83 (4): 595–634. doi:10.1017/S0263593300003333. ISSN 1473-7116.

- ^ Sensenig, Andrew T.; Shultz, Jeffrey W. (2003-02-15). “Mechanics of cuticular elastic energy storage in leg joints lacking extensor muscles in arachnids” (英語). Journal of Experimental Biology 206 (4): 771–784. doi:10.1242/jeb.00182. ISSN 1477-9145.

- ^ a b c d “Discover Life in America- GSMNP Pseudoscorpions”. 2021年12月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b Judson, Mark L. I. (2012). “Reinterpretation of Dracochela deprehendor (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones) as a stem-group pseudoscorpion” (英語). Palaeontology 55 (2): 261–283. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01134.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

関連項目

[編集]Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.