Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

James Cook

British explorer and naval officer (1728–1779) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

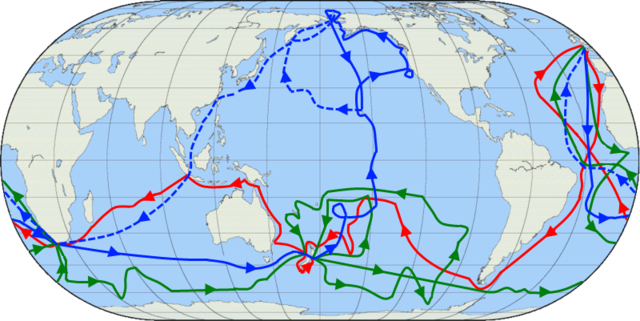

Captain James Cook (7 November [O.S. 27 October] 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, cartographer, and naval officer famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 to the Pacific and Southern Oceans. He completed the first recorded circumnavigation of the main islands of New Zealand and was the first known European to visit the eastern coastline of Australia and the Hawaiian Islands.

Remove ads

Cook joined the British merchant navy as a teenager and joined the Royal Navy in 1755. He served during the Seven Years' War and subsequently surveyed and mapped much of the entrance to the St. Lawrence River during the siege of Quebec. In the 1760s he mapped the coastline of Newfoundland and made astronomical observations there which brought him to the attention of the Admiralty and the Royal Society. This acclaim came at a crucial moment for the direction of British overseas exploration, and it led to his commission in 1768 as commander of HMS Endeavour for the first of three Pacific voyages.

In these voyages, Cook sailed thousands of miles across largely uncharted areas of the globe. He mapped coastlines, islands and features from New Holland to Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean in greater detail and on a scale not previously charted by Western explorers. He made contact with numerous indigenous peoples and claimed various territories for Britain. He displayed a combination of seamanship, superior surveying and cartographic skills, physical courage, and an ability to lead men in adverse conditions.

In 1779, on his second visit to Hawaii, he was killed when a dispute with indigenous Hawaiians turned violent. Cook left a legacy of scientific and geographical knowledge that influenced his successors well into the 20th century, and numerous memorials worldwide have been dedicated to him. He remains controversial for his occasionally violent encounters with indigenous peoples and there is debate on whether he can be held responsible for paving the way for British imperialism and colonialism.

Remove ads

Early life and family

Summarize

Perspective

James Cook was born on 7 November [O.S. 27 October] 1728 in the village of Marton in the North Riding of Yorkshire and baptised on 14 November (N.S.) in the parish church of St Cuthbert where his name can be seen in the church register.[1][2] He was the second of eight children of James Cook (1693–1779), a Scottish farm labourer from Ednam in Roxburghshire, and his locally born wife, Grace Pace (1702–1765), from Thornaby-on-Tees.[1][3][4] In 1736, his family moved to Airey Holme farm at Great Ayton, where his father's employer, Thomas Skottowe, paid for him to attend the local school.[5] In 1741, after five years of schooling, he began work for his father who had been promoted to farm manager. For leisure, he would climb a nearby hill, Roseberry Topping, enjoying the opportunity for solitude.[6]

In 1745, when he was 16, Cook moved 20 miles (32 km) to the fishing village of Staithes to be apprenticed as a shop boy to grocer and haberdasher William Sanderson.[1] Historian Vanessa Collingridge speculated that this is where Cook first felt the lure of the sea while gazing out of the shop window.[7]

After 18 months, not proving suited for shop work, Cook travelled to the nearby port town of Whitby to be introduced to Sanderson's friends John and Henry Walker. The Walkers, who were Quakers, were prominent local ship-owners in the coal trade.[8][9] Their house is now the Captain Cook Memorial Museum.[10] Cook was taken on as a merchant navy apprentice in their small fleet of vessels, plying coal along the English coast. His first assignment was aboard the collier Freelove, and he spent several years on this and various other coasters, sailing between the Tyne and London. As part of his apprenticeship, Cook applied himself to the study of algebra, geometry, trigonometry, navigation and astronomy – all skills he would need one day to command his own ship.[11]

His three-year apprenticeship completed, Cook began working on merchant ships in the Baltic Sea. After passing his examinations in 1752, he soon progressed through the merchant navy ranks, starting with his promotion in that year to mate aboard the collier brig Friendship.[12] In 1755, within a month of being offered command of this vessel, he volunteered for service in the Royal Navy, when Britain was re-arming for what was to become the Seven Years' War. Despite the need to start at the bottom of the naval hierarchy, Cook realised his career would advance more quickly in military service and entered the Navy at Wapping on 17 June 1755.[13]

On 21 December 1762, Cook married Elizabeth Batts, the daughter of Samuel Batts – keeper of the Bell Inn in Wapping and one of Cook's mentors – at St Margaret's Church, Barking, Essex.[14][15][a] The couple had six children: James (1763–1794), Nathaniel (1764–1780, lost aboard HMS Thunderer which foundered with all hands in a hurricane in the West Indies), Elizabeth (1767–1771), Joseph (1768–1768), George (1772–1772) and Hugh (1776–1793, who died of scarlet fever while a student at Christ's College, Cambridge). When not at sea, Cook lived in the East End of London. He attended St Paul's Church, Shadwell, where his son James was baptised. Cook has no direct descendants – all of his children died before having children of their own.[16]

David Samwell, a Welsh surgeon who accompanied Cook on the third voyage, described him as: "... above six feet high, and though a good looking man, he was plain both in address and appearance. His head was small, his hair, which was dark brown, he wore tied behind. His face was full of expression, his nose exceedingly well shaped, his eyes which were of a brown cast, were quick and piercing: his eyebrows prominent, which gave his countenance altogether an air of austerity."[17]

Remove ads

Start of Royal Navy career

Summarize

Perspective

Cook's first posting was with HMS Eagle, serving as able seaman and master's mate under Captain Joseph Hamar for his first year aboard, and Captain Hugh Palliser thereafter.[18] In October and November 1755, he took part in Eagle's capture of one French warship and the sinking of another, following which he was promoted to boatswain in addition to his other duties.[13] His first temporary command was in March 1756 when he was briefly master of Cruizer, a small cutter attached to Eagle while on patrol.[13][19] In June 1757, Cook passed his master's examinations at Trinity House, Deptford, qualifying him to navigate and handle a ship of the King's fleet.[20] He then joined the sixth-rate frigate HMS Solebay as master under Captain Robert Craig.[21][b]

Canada

During the Seven Years' War, Cook served in North America as master aboard the fourth-rate Navy vessel HMS Pembroke.[23] With others in Pembroke's crew, he took part in the major amphibious assault that captured the Fortress of Louisbourg from the French in 1758, and in the siege of Quebec City in 1759.[24]

The day after the fall of Louisbourg, Cook met an army officer, Samuel Holland, who was using a plane table to survey the area. The two men had an immediate connection through their interest in surveying, and Holland taught Cook the methods he was using. They collaborated on developing preliminary charts of the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River, with Cook most likely the author of sailing directions for the river, written in 1758. The combination of Holland's land-surveying techniques[c] and Cook's hydrographic skills enabled the latter, from that time onwards, to produce nautical charts for coastal areas that substantially exceeded the accuracy of such Admiralty charts of the time.[25][26] As General Wolfe's advance on Quebec progressed in 1759, Cook and the other masters of ships in the English fleet worked to chart and mark the shoals of the river, particularly near to Quebec itself. The close approach by the ships of the Royal Navy through these shallow waters allowed General Wolfe to make his famous stealth attack during the 1759 Battle of the Plains of Abraham.[27][28]

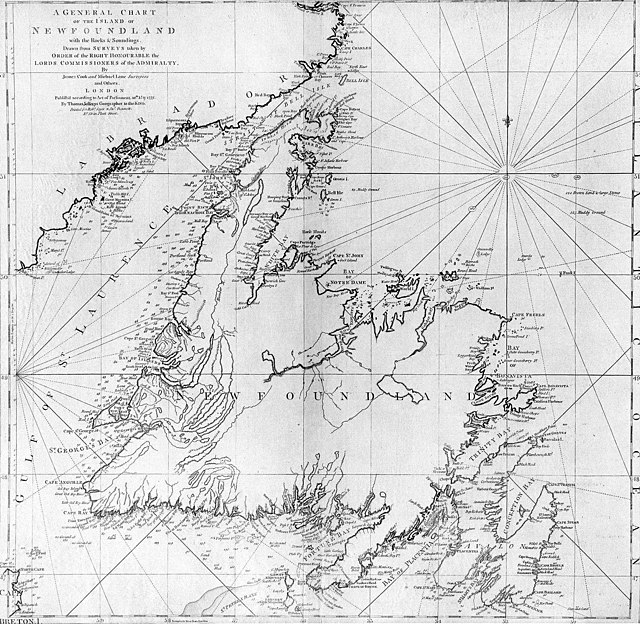

Cook's surveying ability was also put to use in mapping the jagged coast of Newfoundland in the 1760s, aboard HMS Grenville. He surveyed the northwest stretch in 1763 and 1764, the south coast between the Burin Peninsula and Cape Ray in 1765 and 1766, and the west coast in 1767. At this time, Cook employed local pilots to point out the "rocks and hidden dangers" along the south and west coasts. During the 1765 season, four pilots were engaged at a daily pay of 4 shillings each: John Beck for the coast west of "Great St Lawrence", Morgan Snook for Fortune Bay, John Dawson for Connaigre and Hermitage Bay, and John Peck for the "Bay of Despair".[29]

While in Newfoundland, Cook also conducted astronomical observations, in particular of the eclipse of the sun on 5 August 1766.[30] By obtaining an accurate estimate of the time of the start and finish of the eclipse, and comparing these with the timings at a known position in England, it was possible to calculate the longitude of the observation site in Newfoundland. This result was communicated to the Royal Society in 1767.[31]

Cook's hydrographic surveys in Newfoundland – conducted over five seasons – produced the first large-scale, accurate maps of the island's coasts. They were the first large-scale surveys to use precise triangulation to establish land outlines.[32] They also gave Cook his mastery of practical surveying, achieved under often adverse conditions, and brought him to the attention of the Admiralty and Royal Society at a crucial moment both in his career and in the direction of British overseas discovery. Cook's charts were used into the 20th century, with copies being referenced by those sailing Newfoundland's waters for 200 years.[33][failed verification]

Remove ads

First voyage (1768–1771)

Summarize

Perspective

The first scientific voyage commanded by Cook was a three-year expedition to the south Pacific Ocean aboard HMS Endeavour, from 1768 to 1771. The voyage was jointly sponsored by the Royal Navy and Royal Society.[d] The aims were to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from the vantage point of Tahiti; to seek evidence of the postulated Terra Australis Incognita (undiscovered southern land); and to claim lands for Britain.[35][36][37] The latter two goals were contained within sealed orders, not to be opened by Cook until he was in Tahiti.[37][e][f]

In early 1768, the Admiralty asked shipwright Adam Hayes to select a vessel for the expedition; he chose the merchant collier Earl of Pembroke.[42][43][g] She was renamed Endeavour by the navy. On 6 May 1768, at age 39, Cook took his examination for the rank of lieutenant – a rank that was required for the captain of a ship armed with the number of guns planned for Endeavour. The promotion to lieutenant was effective on 25 May 1768, the date he took command.[44][45][46][47][48][h] Like most colliers, Endeavor had a large hold, a sturdy construction that would tolerate grounding, was small enough to be careened for repairs, and had a small draft that enabled navigating in shallows.[50][51] Upon completion of the first voyage, Cook wrote "It was to these properties in her, those on board owe their Preservation. Hence I was enabled to prosecute Discoveries in those Seas so much longer than any other Man ever did or could do."[50] When selecting ships in 1771 for his second voyage, Cook chose the same type of ship, from the same shipbuilder.[52]

The Admiralty authorised a ship's company of 73 sailors and 12 Royal Marines.[53] Cook's second lieutenant was Zachary Hicks, and his third lieutenant was John Gore, a 16-year Naval veteran who had circumnavigated the world in 1766 aboard HMS Dolphin.[54][55] Also on the ship were astronomer Charles Green and botanist Joseph Banks. Banks provided funding for seven others to join the journey, including naturalists, artists, a secretary, and two black servants.[56]

Transit of Venus

The expedition departed England on 26 August 1768.[57] Cook and his crew rounded Cape Horn and continued westward across the Pacific, arriving at Tahiti on 13 April 1769, where the observations of the transit were made.[58] However, the result of the observations was not as conclusive or accurate as had been hoped. Once the observations were completed, Cook opened the sealed orders, which instructed him to search for the postulated southern continent of Terra Australis.[59]

New Zealand and Australia

Cook then sailed to New Zealand where he mapped the complete coastline, making only some minor errors. With the aid of Tupaia, a Tahitian priest who had joined the expedition, Cook was the first European to communicate with the Māori.[60] However, at least eight Māori were killed in violent encounters.[61] Cook then voyaged west, reaching the southeastern coast of Australia near today's Point Hicks on 19 April 1770,[62][i] and in doing so his expedition became the first recorded Europeans to have encountered its eastern coastline.[63]

On 23 April, he made his first recorded direct observation of Aboriginal Australians at Brush Island near Bawley Point, noting in his journal: "... and were so near the Shore as to distinguish several people upon the Sea beach they appear'd to be of a very dark or black Colour but whether this was the real colour of their skins or the C[l]othes they might have on I know not."[64]

Endeavour continued northwards along the coastline, keeping the land in sight with Cook charting and naming landmarks as he went. On 29 April, Cook and crew made their first landfall on the continent at a beach now known as Silver Beach on Botany Bay.[j] Two Gweagal men of the Dharawal / Eora nation opposed their landing and in the confrontation one of them was shot and wounded.[65][66][67]

Cook and his crew stayed at Botany Bay for a week, collecting water, timber, fodder and botanical specimens and exploring the surrounding area. Cook sought to establish relations with the Indigenous population without success.[68][69] At first Cook named the inlet "Sting-Ray Harbour" after the many stingrays found there. This was later changed to "Botanist Bay" and finally "Botany Bay", after the unique specimens retrieved by the botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander.[70] This first landing site was later to be promoted (particularly by Joseph Banks) as a suitable candidate for situating a settlement and British colonial outpost.[71]

After his departure from Botany Bay, he continued northwards. He stopped at Bustard Bay (now known as Seventeen Seventy) on 23 May 1770. On 24 May, Cook and Banks and others went ashore. Continuing north, on 11 June a mishap occurred when Endeavour ran aground on a shoal of the Great Barrier Reef.[72][73] The ship was badly damaged, and in danger of sinking, so Cook ordered all excess weight thrown overboard, including six cannons. A large hole was discovered in the hull, underwater, so the crew fothered the damage (hauled a spare sail under the ship to cover and slow the leak).[72] Cook then careened the ship on a beach at the mouth of the Endeavour River for seven weeks while repairs were undertaken.[74][75]

The voyage then continued and at about midday on 22 August 1770, they reached the northernmost tip of the coast and, without leaving the ship, Cook named it York Cape (now Cape York).[76] Leaving the east coast, Cook turned west and nursed his battered ship through the dangerously shallow waters of Torres Strait. Searching for a vantage point, Cook saw a steep hill on a nearby island from the top of which he hoped to see "a passage into the Indian Seas". Cook named the island Possession Island, where he claimed the entire coastline that he had just explored as British territory.[77]

Return to England

Cook returned to England via Batavia (modern Jakarta, Indonesia), where he put in for repairs. While in Batavia, seven of his crew died from malaria, and 40 were sickened.[78] From Batavia, he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope, then to the island of Saint Helena, arriving on 30 April 1771.[79] The ship finally returned to England on 12 July 1771, anchoring in the Downs, and Cook disembarked to go to the town of Deal in Kent.[80][k]

Shortly after his return, Cook was promoted in August 1771 to the rank of commander.[81][82] Cook's journal of the first voyage was published in 1773.[83][84][l] Banks received accolades from the press and the scientific community.[85] Banks planned to travel with Cook in the second voyage, but his excessive demands for modifications to the ship conflicted with the Admiralty's constraints, so he removed himself from the voyage before it departed.[86] Cook's son George was born five days before he left for the second voyage.[87]

Remove ads

Second voyage (1772–1775)

Summarize

Perspective

In 1772, Cook was commissioned to lead another scientific expedition on behalf of the Royal Society, with the goal of determining if the hypothetical landmass Terra Australis existed or not.[88][89]

This voyage would have two ships and, unlike the first voyage, Cook selected them himself: HMS Resolution commanded by Cook, and HMS Adventure, commanded by Tobias Furneaux.[90][89] Resolution began her career as the North Sea collier Marquis of Granby, launched at Whitby in 1770. She was fitted out at Deptford with the most advanced navigational aids of the day, including an azimuth compass, ice anchors and the latest apparatus for distilling fresh water from sea water.[91]

Crew included astronomer William Wales (responsible for the new K1 chronometer carried on the Resolution), lieutenant Charles Clerke, artist William Hodges, and naturalists Johann Reinhold Forster and his son, Georg Forster.[92]

Searching for Terra Australis

After departing England, the ships travelled to South Africa and stopped at Cape Town in November 1772. From there they sailed eastward, planning to circumnavigate the globe roughly between 50°S and 70°S latitude.[m] In late November 1772, the ships sighted the first icebergs and Cook performed an experiment: his crew chopped blocks of ice from ice flows and melted them onboard the ships, producing good quality fresh water, proving that drinking water could be obtained from sea ice.[94] On 17 January 1773 the crews became the first recorded Europeans to cross the Antarctic Circle.[95][96] Despite his mission to find Terra Australis, Cook never sighted Antarctica in any of his voyages; but on 18 January – unbeknownst to him – the ships approached within 75 miles (121 km) of Antarctica.[95]

In February 1773, in the Antarctic fog, Resolution and Adventure became separated.[97] Furneaux made his way, via Tasmania,[n] to a pre-arranged rendezvous location to be used in the event of separation: Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand; Cook arrived in May, after Furneaux.[98] The crews traded with the Māori people, and in his journal, Cook lamented the fact that Europeans were possibly transmitting diseases to the indigenous people and encouraging prostitution.[99]

In June, the ships departed New Zealand, and headed south – in the middle of the southern winter – to resume their eastward search for Terra Australis at about 60°S.[100] The next month, 20 crewmen of the Adventure contracted scurvy because Furneaux had failed to follow Cook's dietary instructions.[101]

The ships then turned north to visit Tahiti, then to Tonga.[102] and then toward New Zealand again, but on the way the ships became separated in a storm.[103] Cook proceeded to the rendezvous point, and waited three weeks, then departed to continue the voyage. Furneaux arrived, missing Cook by four days.[104] While resupplying their ship in Queen Charlotte Sound, eleven members of the crew of Adventure fought with some Maori, resulting in the deaths of all eleven crew and two Maori. Furneaux later discovered the bodies of the crew members, partially burned in preparation for cannibalism.[105] When learning about the deaths much later, Cook suspected that Furneaux's crew was at fault, writing "I must ... observe in favor of the New Zealanders that I have always found them of a brave, noble, open and benevolent disposition".[106] The Adventure departed New Zealand and quickly returned to Britain.[107][o]

The Resolution, now alone, continued her search for Terra Australis, reaching her most southern latitude of 71°10′S in January 1774.[109] When his ship reached that southernmost point, and progress was blocked by impenetrable pack ice, Cook wrote in his private diary: "I whose ambition leads me not only farther than any other man has been before me, but as far as I think it possible for man to go...".[20][110]

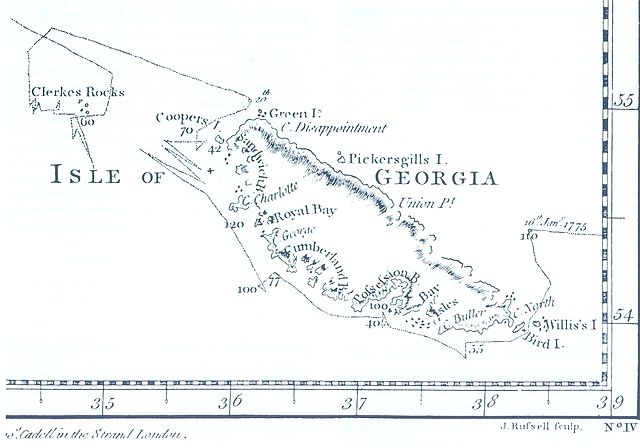

From there, the Resolution made a large anti-clockwise circle, visiting Easter Island, Tofua, Melanesia, and New Zealand.[111][p] They then proceeded home, sailing south of Tierra del Fuego, and stopping at South Georgia Island, where Cook claimed it in the name of his king.[113] The ship then travelled to South Africa, then north back to Britain.[114][q][r]

Return to England

Cook was promoted to the rank of post-captain and given an honorary retirement from the Royal Navy, with a posting as an officer of the Greenwich Hospital.[116] He reluctantly accepted, insisting that he be allowed to quit the post if an opportunity for active duty should arise.[117] His fame extended beyond the Admiralty; he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society and awarded the Copley Gold Medal for completing his second voyage without losing a man to scurvy.[118] Nathaniel Dance-Holland painted his portrait; he dined with James Boswell; he was described in the House of Lords as "the first navigator in Europe".[20]

Remove ads

Third voyage (1776–1779)

Summarize

Perspective

The primary purpose of Cook's third expedition was to search for a Northwest Passage from the north Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic.[119][120][s] To keep this goal secret, the Admiralty publicly stated that the aim of the mission was to return Omai to his home in Tahiti.[121][120][t]

On this voyage, Cook again commanded HMS Resolution, while Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery.[123][u] Cook's lieutenants included John Gore and James King.[123] William Bligh – who would later command HMS Bounty – was the master.[123] William Anderson was surgeon and botanist, William Bayly served as astronomer, and John Webber was the official artist.[123] Among the midshipmen was George Vancouver, who would later lead the Vancouver Expedition.[123]

Hawaii

The third voyage began by sailing around South Africa, then into the Pacific Ocean. After stopping in New Zealand, the expedition returned Omai to his homeland of Tahiti. Cook then traveled north and became the first recorded European to encounter the Hawaiian Islands.[124][v] After his initial landfall in January 1778 at Waimea harbour, Kauai, Cook named the archipelago the "Sandwich Islands" after the fourth Earl of Sandwich—the acting First Lord of the Admiralty.[124]

North America

From Hawaii, Cook sailed north and then northeast to explore the west coast of North America north of the Spanish settlements in Alta California. He sighted the Oregon coast at approximately 44°30′ north latitude, naming Cape Foulweather, after the bad weather which forced his ships south to about 43° north before they could begin their exploration of the coast northward.[126] He unknowingly sailed past the Strait of Juan de Fuca and soon after entered Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island.[127] He anchored near the First Nations village of Yuquot.[citation needed] Cook's two ships remained in Nootka Sound from 29 March to 26 April 1778, in what Cook called Ship Cove, now Resolution Cove,[128] at the south end of Bligh Island.[w]

After leaving Nootka Sound in search of the Northwest Passage, Cook explored and mapped the coast all the way to the Bering Strait, on the way identifying what came to be known as Cook Inlet in Alaska.[126] In a single visit, Cook charted the majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first time, determined the extent of Alaska, and closed the gaps in Russian (from the west) and Spanish (from the south) exploratory probes of the northern limits of the Pacific.[20]

By the second week of August 1778, Cook had sailed through the Bering Strait, crossed the Arctic Circle, and sailed into the Chukchi Sea.[130] He headed northeast up the coast of Alaska until he was blocked by sea ice at a latitude of 70°44′ north.[131] Cook then sailed west to the Siberian coast, and then southeast down the Siberian coast back to the Bering Strait.[132] By early September 1778, he was back in the Bering Sea to begin the trip to back to Hawaii.[133] Cook became increasingly frustrated and irritable on this voyage, and sometimes exhibited irrational behaviour towards his crew, such as forcing them to eat walrus meat, which they considered inedible.[134][135][136]

Return to Hawaii

Cook returned to Hawaii in 1779. The ships sailed throughout the archipelago for eight weeks, surveying and trading.[137][x] After stops in Maui and Kauai, Cook made landfall at Kealakekua Bay on Hawai'i Island, the largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago.[139]

On the large island, Cook met with the Hawaiian king Kalaniʻōpuʻu, who treated Cook with respect, and invited him to participate in several ceremonies. The king and Cook exchanged gifts, and the king presented Cook with a ʻahuʻula (feathered cloak).[140] Some members of Cook's crew concluded that the Hawaiian's considered Cook a deity, and that interpretation (specifically, that Cook was considered to be the Polynesian god Lono) has been endorsed by some academics.[141][142][143][y] Other scholars, including Gananath Obeyesekere, assert that the Hawaiians did not consider Cook to be a deity.[146][z]

Death

After a month's stay, Cook left Hawaii to resume his exploration of the northern Pacific. But shortly after departure a strong gale caused Resolution's foremast to break, so the ships returned to Kealakekua Bay for repairs.[147]

Relations between the crew and the Hawaiians were already strained before the departure, and they grew worse when the ship returned for repairs.[148][aa] Numerous quarrels broke out and petty thefts was common. On 13 February 1779, a group of Hawaiians stole one of Cook's cutters.[150][151]

The following day, Cook responded to the theft by attempting to kidnap and ransom the king, Kalaniʻōpuʻu.[152] Cook and a small party marched through the village to retrieve the king.[153] Cook led Kalaniʻōpuʻu away; as they got to the boats, one of Kalaniʻōpuʻu's favourite wives, Kānekapōlei, and two chiefs approached the group. They pleaded with the king not to go and a large crowd began to form at the shore.[154] News reached the Hawaiians that on the other side of the bay, high-ranking Hawaiian chief Kalimu had been shot whilst trying to break through a British blockade. This exacerbated the tense situation.[155] As the Europeans launched the boats to leave, Cook was struck on the head by the villagers and then stabbed to death as he fell on his face in the surf.[155][156] He was first struck on the head with a club by a chief named Kalaimanokahoʻowaha or Kanaʻina[ab] and then stabbed by one of the king's attendants, Nuaa.[158][159][157][ac] Cook collapsed and died on the shore, and Hawaiian warriors crowded around the corpse to bludgeon it.[160]

Aftermath

Following the death of Cook and the four marines, the bodies were taken by Hawaiians inland to a village.[161][ad] King took a boat to the opposite shore, and was approached by a priest who offered to intercede and ask for the remains to be returned; King consented.[163] Some crewmen returned to the location of the attack, and skirmishes broke out, resulting in the death of several Hawaiians.[161] The following day, some of Cooks remains were returned to the Resolution, including some charred flesh, several bones, the skull, and the hands with the skin still attached. The crew placed the remains in a weighted box, and buried their captain at sea.[161][163]

Clerke assumed leadership of the expedition and made a final attempt to pass through the Bering Strait.[164] He died of tuberculosis on 22 August 1779 and John Gore, a veteran of Cook's first voyage, took command of Resolution and of the expedition. James King replaced Gore in command of Discovery.[165] The expedition returned home, reaching England on 4 October 1780.[ae] After their arrival in England, King completed Cook's account of the voyage.[166][167]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Ethnographic collections

The largest collection of artefacts from Cook's voyages is the Cook-Forster Collection held at the University of Göttingen.[168][af]

The Australian Museum in Sydney holds over 250 objects associated with Cook's voyages. The objects are mostly from Polynesia although there are also artefacts from the Solomon Islands, North America and South America. Many of the artefacts were collected during first contact between Europeans and indigenous peoples of the Pacific.[169][170]

Navigation

Cook's three voyages to the Pacific Ocean contributed much to Europeans' knowledge of the area. Several islands, such as the Hawaiian group, were encountered for the first time by Europeans, and his accurate navigational charting of large areas of the Pacific contributed to the fields of hydrographic and geographic knowledge.[172]

On his second and third voyages, Cook carried the K1 chronometer made by Larcum Kendall – if the device could accurately keep time for long spans of time, while withstanding the violent motions of a ship, it would effectively solve the longitude problem that had troubled mariners for centuries. The chronometer was the shape of a large pocket watch, 5 inches (13 cm) in diameter. It was a copy of the H4 clock made by John Harrison, which proved to be the first to keep accurate time at sea when used on the ship Deptford's journey to Jamaica in 1761–62.[173] Cook's log was full of praise for this time-piece.[174]

Science

Cook was a pioneer in the prevention of scurvy. He succeeded in circumnavigating the world on his first voyage without losing a single man to scurvy, an unusual accomplishment at the time. He tested several preventive measures, most importantly the frequent replenishment of fresh food.[175] For presenting a paper on this aspect of the voyage to the Royal Society he was presented with the Copley Medal in 1776.[176][177] Cook became the first European to have extensive contact with various people of the Pacific. He correctly postulated a link among all the Pacific peoples, despite their being separated by great ocean stretches . Cook theorised that Polynesians originated from Asia, which scientist Bryan Sykes later verified.[178] In New Zealand the coming of Cook is often used to signify the onset of the colonisation.[179]

Cook carried several scientists on his voyages; they made significant observations and discoveries. Two botanists, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, sailed on the first voyage and collected over 3,000 plant species.[180] Banks subsequently promoted British settlement of Australia, leading to the establishment of New South Wales as a penal settlement in 1788.[181][182] Artists also sailed on Cook's first voyage. Sydney Parkinson was heavily involved in documenting the botanists' findings, completing 264 drawings before his death near the end of the voyage.[183][184] The drawings, many published in Banks' Florilegium, were of immense scientific value to British botanists.[184][185][183] Cook's second expedition included William Hodges, who produced notable landscape paintings of Tahiti, Easter Island, and other locations.

Several officers who served under Cook went on to distinctive accomplishments. William Bligh, Cook's sailing master, was given command of HMS Bounty in 1787 to sail to Tahiti and return with breadfruit. Bligh became known for the mutiny of his crew, which resulted in his being set adrift in 1789. He later became Governor of New South Wales, where he was the subject of another mutiny—the 1808 Rum Rebellion.[186] George Vancouver, one of Cook's midshipmen, led a voyage of exploration to the Pacific Coast of North America from 1791 to 1794.[187] In honour of Vancouver's former commander, his ship was named Discovery. George Dixon, who sailed under Cook on his third expedition, later commanded his own.[188]

Cook's contributions to knowledge gained international recognition during his lifetime. In 1779, while the American colonies were fighting Britain for their independence, Benjamin Franklin wrote to captains of colonial warships at sea, recommending that if they came into contact with Cook's vessel, they were to "not consider her an enemy, nor suffer any plunder to be made of the effects contained in her, nor obstruct her immediate return to England by detaining her or sending her into any other part of Europe or to America; but that you treat the said Captain Cook and his people with all civility and kindness ... as common friends to mankind."[189]

Memorials

United Kingdom

One of the earliest monuments to Cook in the United Kingdom is located at The Vache, erected in 1780 by Admiral Hugh Palliser, a contemporary of Cook and one-time owner of the estate.[190] A large obelisk was built in 1827 as a monument to Cook on Easby Moor overlooking his boyhood village of Great Ayton,[191] along with a smaller monument at the former location of Cook's cottage.[192] There is also a monument to Cook in the church of St Andrew the Great, St Andrew's Street, Cambridge, where his sons Hugh, a student at Christ's College, and James were buried. Cook's widow Elizabeth was also buried in the church and in her will left money for the memorial's upkeep. The 250th anniversary of Cook's birth was marked at the site of his birthplace in Marton by the opening of the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum, located within Stewart Park (1978). A granite vase just to the south of the museum marks the approximate spot where he was born.[193] Tributes also abound in post-industrial Middlesbrough, including a primary school,[194] shopping square[195] and the Bottle 'O Notes, a public artwork by Claes Oldenburg, that was erected in the town's Central Gardens in 1993. Also named after Cook is James Cook University Hospital, a major teaching hospital which opened in 2003 with a railway station serving it called James Cook opening in 2014.[196] The Royal Research Ship RRS James Cook was built in 2006 to replace the RRS Charles Darwin in the UK's Royal Research Fleet,[197] and Stepney Historical Trust placed a plaque on Free Trade Wharf in the Highway, Shadwell to commemorate his life in the East End of London. A statue erected in his honour can be viewed near Admiralty Arch on the south side of The Mall in London. In 2002, Cook was placed at number 12 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[198]

Australia

Cooks' Cottage, his parents' last home, which he is likely to have visited, is now in Melbourne, Australia, having been moved from England at the behest of the Australian philanthropist Sir Russell Grimwade in 1934.[199][200][201] The first institution of higher education in North Queensland, Australia, was named after him, with James Cook University opening in Townsville in 1970.[202]

There are statues of Cook in Hyde Park in Sydney, and at St Kilda in Melbourne.[203]

In 1959, the Cooktown Re-enactment Association first performed a re-enactment of Cook's 1770 landing at the site of modern Cooktown, Australia, and have continued the tradition each year, with the support and participation of many of the local Guugu Yimithirr people. They celebrate the first act of reconciliation between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous people, when a Guugu Yimithirr elder stepped in after some of Cook's men had violated custom by taking green turtles from the river and not sharing with the local people. He presented Cook with a broken-tipped spear as a peace offering, thus preventing possible bloodshed. Cook recorded the incident in his journal.[204]

United States

A U.S. coin, the 1928 Hawaii Sesquicentennial half-dollar, carries Cook's image. Minted for the 150th anniversary of his discovery of the islands, its low mintage (10,008) has made this example of an early United States commemorative coin both scarce and expensive.[205] The site where he was killed in Hawaii was marked in 1874 by a white obelisk. This land (5,681 square feet) although in Hawaii, was purportedly deeded to Britain in 1877 by Princess Likelike and her husband, Archibald Scott Cleghorn.[206][207][208][ag] A nearby town is named Captain Cook, Hawaii; several Hawaiian businesses also carry his name. The Apollo 15 Command/Service Module Endeavour,[209] the Space Shuttle Endeavour,[210] and the Crew Dragon Endeavour;[211] are named after Cook's ship. Another Space Shuttle, Discovery, was named after Cook's HMS Discovery.[212] There is also a statue of Cook at Resolution Park in Anchorage, Alaska.[citation needed]

Canada

A statue of James Cook in Victoria, BC, Canada was constructed in 1976. The statue was destroyed by protestors in 2021.[213]

Places named after Cook

Cook's name has been given to the Cook Islands, Cook Strait, Cook Inlet and the Cook crater on the Moon.[214] Aoraki / Mount Cook, the highest summit in New Zealand, is named for him.[215] Another Mount Cook is on the border between the U.S. state of Alaska and the Canadian Yukon territory.[216]

Culture

Cook has been a subject in many literary creations. Letitia Elizabeth Landon, a popular poet known for her sentimental romantic poetry,[217] published a poetical illustration to a portrait of Captain Cook in 1837.[218] In 1931, Kenneth Slessor's poem "Five Visions of Captain Cook" was the "most dramatic break-through" in Australian poetry of the 20th century according to poet Douglas Stewart.[219]

Cook appears as a symbolic and generic figure in several Aboriginal myths, often from regions where Cook did not encounter Aboriginal people. Maddock states that Cook is usually portrayed as the bringer of Western colonialism to Australia and is presented as a villain who brings immense social change.[220]

Cook has been depicted in numerous films, documentaries and dramas.[221][222][223]

Controversy

The period 2018 to 2021 marked the 250th anniversary of Cook's first voyage of exploration. Several countries, including Australia and New Zealand, arranged official events to commemorate the voyage,[224][225] leading to widespread public debate about Cook's legacy and the violence associated with his contacts with Indigenous peoples.[226][227] In the lead-up to the commemorations, various memorials to Cook in Australia and New Zealand were vandalised, and there were public calls for their removal or modification due to their alleged promotion of colonialist narratives.[228][229] There were also campaigns for the return of Indigenous artefacts taken during Cook's voyages.[230][ah]

In July 2021, a statue of Cook in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, was torn down in protests about the deaths of Indigenous residential school children in Canada.[232] In January 2024, a statue of Cook in St Kilda, Melbourne was cut down in a protest against colonialism; the premier of Victoria pledged to work with the local council to repair the statue.[233][203][234]

Alice Proctor argues that the controversies over public representations of Cook and the display of Indigenous artefacts from his voyages are part of a broader debate over the decolonisation of museums and public spaces and resistance to colonialist narratives.[235] While a number of commentators argue that Cook enabled British imperialism and colonialism in the Pacific,[226][236][237][238] Geoffrey Blainey, among others, notes that Banks promoted Botany Bay as a site for colonisation after Cook's death.[239] Robert Tombs has defended Cook, arguing: "He epitomized the Age of Enlightenment in which he lived" and in conducting his first voyage "was carrying out an enlightened mission, with instructions from the Royal Society to show 'patience and forbearance' towards native peoples".[240]

Remove ads

Arms

|

|

Remove ads

See also

- List of Australian places named by James Cook

- Death of Cook – Paintings depicting Cook's death

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration – 1600–1930 period of research-driven expeditions

- List of places named after Captain James Cook

- New Zealand places named by James Cook – List of geographic locations named by explorer James Cook

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads